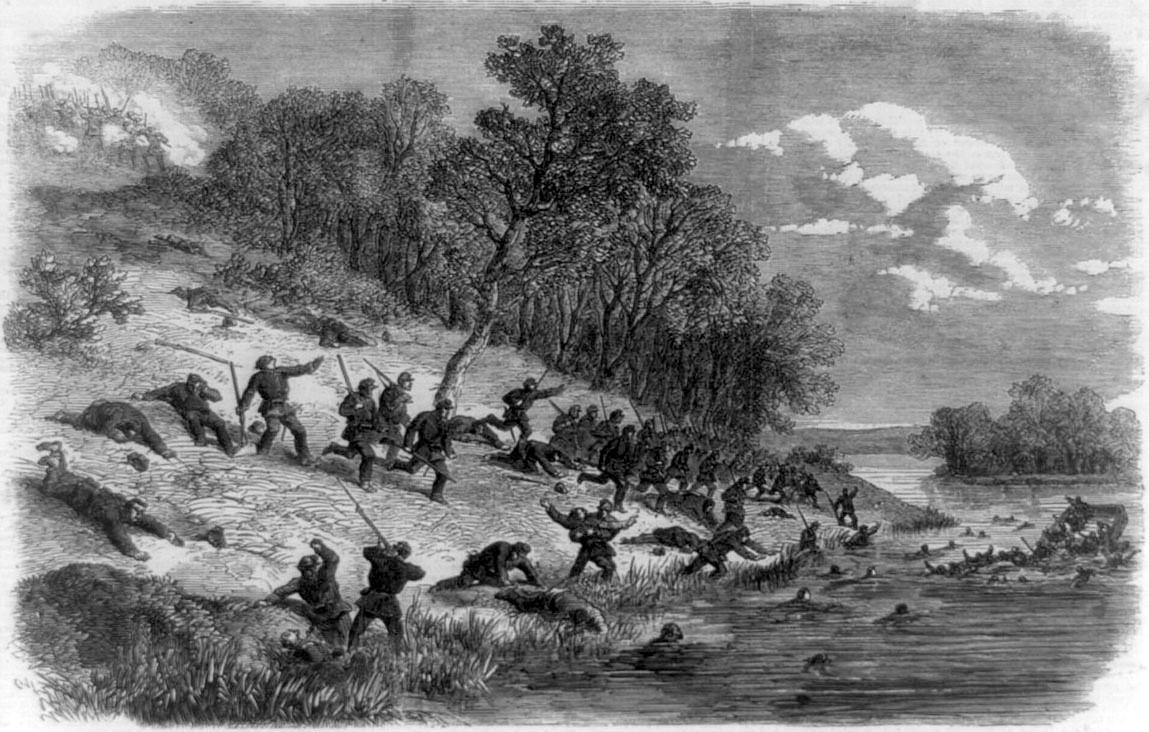

Carrying a regiment’s colors into battle was considered an honor and a privilege. It was also a dangerous job and would likely get a man maimed or killed. Thus, it required a great deal of courage. Just at this time, David was very much interested in the Rebel color-bearer. The enemy was only two or three rods from him. The company’s line was broken on the left, and their right was attacked in the flank. There was nothing left to do but retire or surrender. This moment was remembered in his diary.

Rebel flag bearer

No date:

We were ordered to fall back, but I did not obey this order with the rest of the regiment, for I was very much interested in the color-bearer. .. .he was coming through the creek in front of us. The creek was about twenty feet wide, and about three feet deep…. He was yelling like an Indian. At the time I was returning ramrod… I thought for the moment I will fix him as soon as I can get a cap on my gun, but while I was placing the cap I changed my mind as the thought occurred he could do very little harm with that rebel rag, that I had better shoot a man with a gun.

Rebels behind a split rail fence

There was a low fence between them about four or five rails high. Another Johnnie Reb was a little in advance of the wild color-bearer with his gun held in his arms. He was just about to reach for the top rail with his left hand, which was about hip-high. When David fired, the young Confederate soldier struck his hand against his side and dropped. He did not come over the fence.

Up to this time, David had been down on his right knee with his left one cocked, which gave him a perfect rest for his elbow during firing. After he had stopped the Reb on the other side of the fence, he arose and drew a cartridge. While he was tearing it, he looked to the rear and saw his men had all fallen back about two rods, firing as they retired.

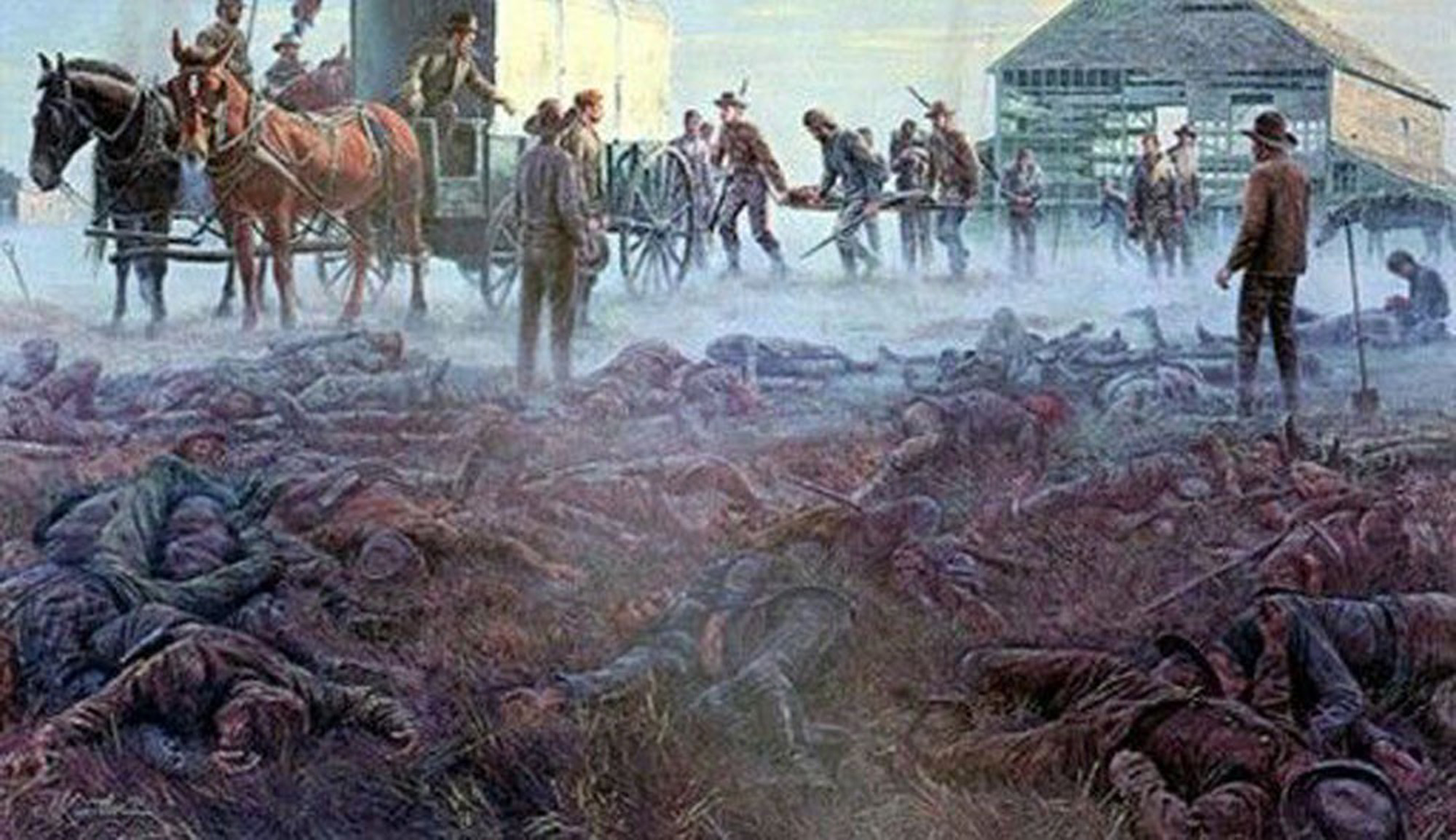

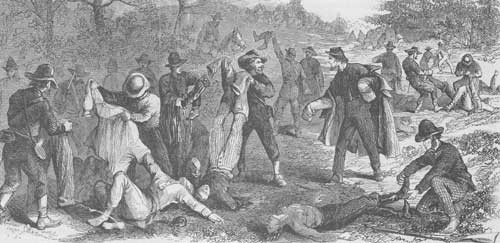

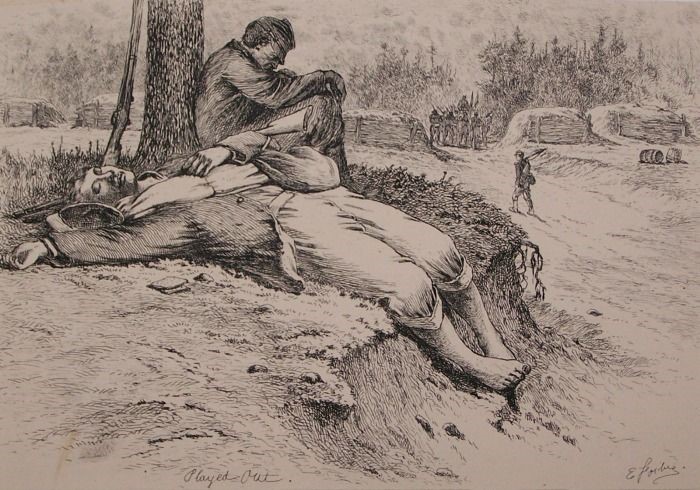

The dead on the field

This gave David a good view of those that were left dead on the first line of battle. It presented a regular swath of blue coats, as far as he could see. They were piled up in every shape, some on their backs, some on their faces, and others turned and twisted in every possible condition. There was a dead man on each side of him. David stood between those two lines of battle, viewing the windrow of human dead, his old comrades, a picture which would never fade from his memory. One which the tongue cannot tell, nor pen describe, though he did his best later in his writing.

They died where they stood

No date:

The bullets were whistling about like hail. I seemed to wear a charmed life, and the bullet was not yet made that could hit me. But I was soon undeceived. I had not gotten back much over two rods when I felt something strike my left knee, as we were in the woods I thought a bullet had struck a chip, and that the chip had hit me on the knee. When I looked at my knee I saw a bullet hole in my pants. I had not gone over five steps when I felt a similar sensation in my other knee. This one had cut a little deeper, which I discovered by pulling up my leg. I was between two brush piles as we were passing out of the woods.

The wounded all around

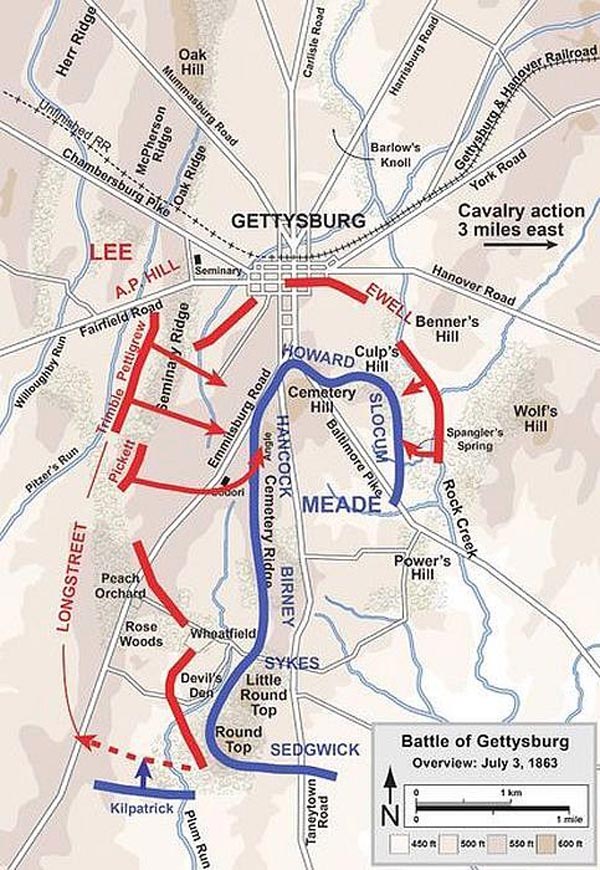

After David was hit the second time, he went over the brush pile and toward the enemy into an open field. It was a sweltering place, where he was under two crossfires and a good far from the rear. Both balls that hit him were from the crossfire. There was a battery about three or four hundred yards in the rear on what they later called Barlow’s Knoll. It was at this place they were ordered to fall back. David expected they would fall back and make a stand. But as soon as he got out of the woods, he saw the battery was limbered up and was retiring. David later wrote down what he saw.

No date:

I witnessed an instance of brave conduct, of which I am possibly the only witness living. In the first day’s fight on a little knoll, the overwhelming rebel forces, as all know, drove our comparatively thin line back. I lay on the ground at the extreme right of the line, with a bullet wound through my knee joint, I remember watching, with mingled apprehension and pride the stubborn retreat of our regiment. After the main body of soldiers had gone back about a hundred yards, I saw Captain Howard Reeder of company G standing not ten feet away. He was deliberately discharging his revolver into the ranks of the onrushing rebels. He then turned and ran. I wondered, “How he ever got away without being killed was a miracle,” since the rebels could not have been more than 15 feet from him. This was certainly the deed of the type of leader that orders his men not, “Go forward here and there,” but “Come along with me, boys.”

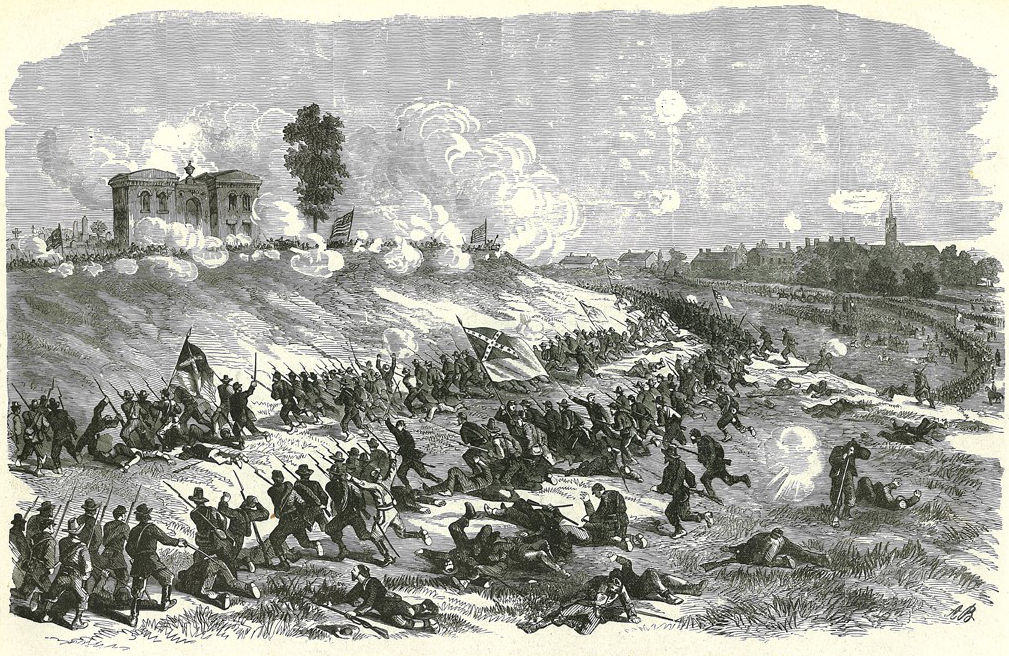

Barlow’s Knoll

The troops were driven back for two miles. After David and a few men got into the open field and took that way out, their right was now their left in retiring. David saw a long line of the enemy closing in on the right, or what had been the right, advancing. This line of battle, over a mile long, was closing in on him like a gate. By the time the troops had reached Barlow’s Knoll, he had worked himself along in a straight line with the red barn at the Almshouse. To his right, the troops were dropping like flies, and to his left was that solid line advancing and firing.

The barn at the Almshouse

No date:

I recollect many things about the boys. At Gettysburg during the first days fighting comrade Philip Halpin was killed between the Almshouse and Barlow’s knoll. I knew sergeant Edward Kiefer. He always looked out for us in dealing out the bread.

David was, at all times, less than one hundred yards from the Rebel line. He passed along their front for nearly a mile till he got to the red barn. Long before then, he could hear the voice of General von Gilsa, who was dismounted. A bay horse came along the line with saddle and bridle on. The general called to the men, “Catch my horse,” which was soon surrounded, and the general was in his saddle in less than a minute.

The old man must have been tickling the horse with his spurs by the twitches of the horse’s tail. It did not take him long to form a battle line about halfway between their first position and the town. He rode up and down that line through a regular storm of lead, meantime using the German epithets so familiar to him. David could hear the words “Rally boys.”

“Rally boys”

No date:

I saw Big Joe Buck, the best fiddler in the company get killed near Barlow’s knoll in the extreme front position our regiment had taken at Gettysburg. I saw where 18 bodies were buried in one grave at that spot. These bodies along with all that could be located elsewhere over the field were taken and buried. All the bodies that could not be identified were placed in tiers of the plot with a special marker. I’m sure Joe Buck in playing a gig in the grave of the, “unknown.”

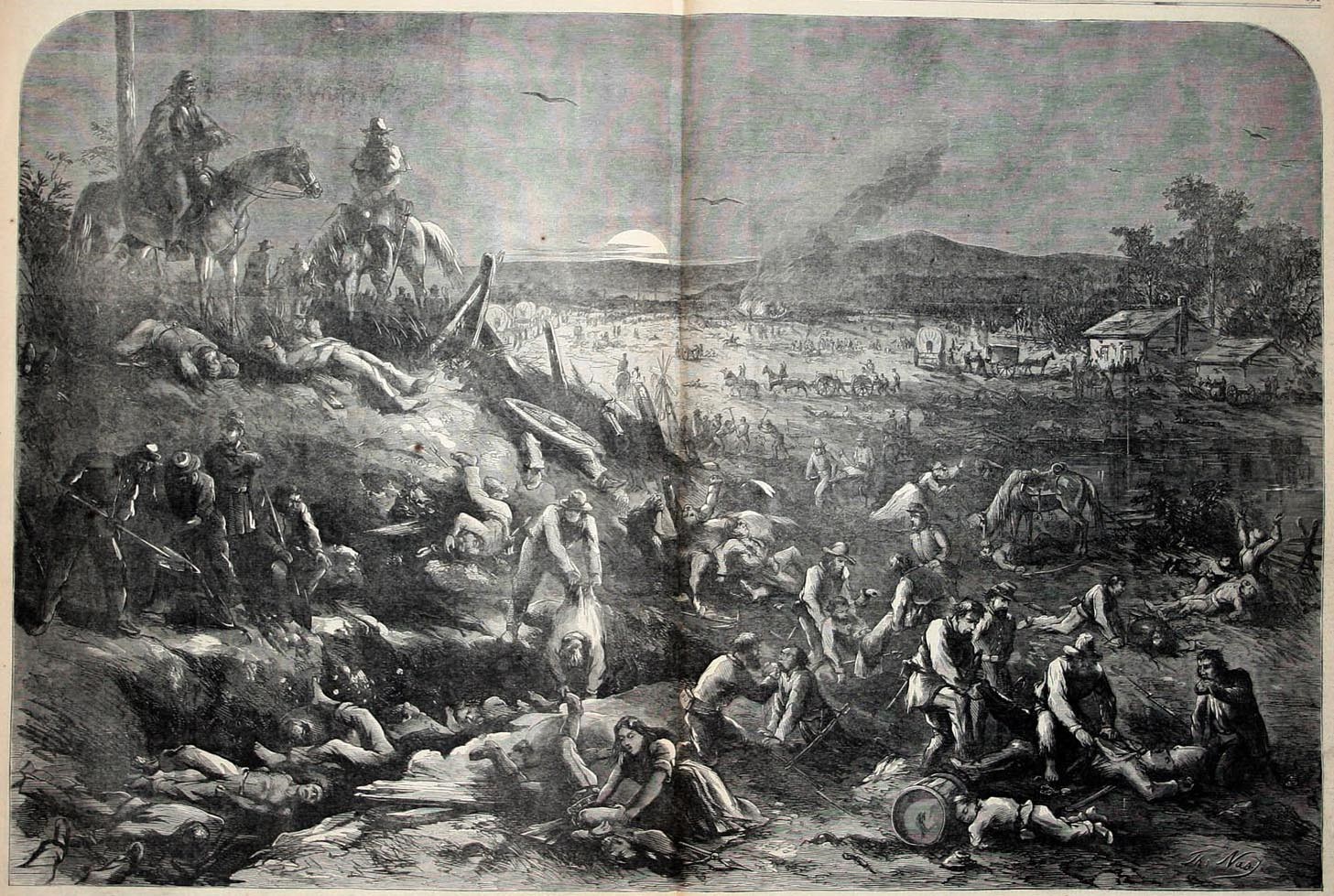

Stripping the dead

Burial of the dead

The line was ordered to fall back. David followed orders, but this still left him and the men between two fires. He finally got to the red barn where the highest post fence he had ever seen confronted them. Joining the other men, he threw his gun over, then commenced to climb it. But it was quite a job to get over that fence with his wounds and a lame leg.

How David would have liked to have entered that barn for a rest, but he knew he must move on or be taken, prisoner. When he got around the barn, he met Captain Howell and Lieutenant Walton of Company H, both members of his regiment. Howell took him by the left arm and Walton by the right, which was a significant improvement. He felt very much pleased with the escort, but it did not last long.

Suddenly the captain stumbled and stated that he had been wounded. Just a second later, the lieutenant fell from a wound and came near, dragging David with him. Walton was a large man, weighing about two hundred and forty pounds. Barnes and Beidelman tried to lift Walton into a window and being very heavy; they could not lift him. They pressed two big privates into the service and kept on as the enemy was only about fifty yards behind. After this, he met Freddy who had a piece of a shell struck in his kneecap and he was quite lame.

About this time, Sergeant Keifer of David’s Company reported the woods in front of them were being massed with men behind the thickets making ready for a charge. He told him it was useless as the force was a heavy one.

David then happened to look up and asked him, “Where is our battle line?”

He looked around and remarked: “It’s gone. Get yourselves out the best you can; report at Cemetery Hill.” Then all the men quickly got out of that dangerous spot.

Retreat

Some men in the skirmish line fired then fell back the usual distance, loading as they went. Then they halted and fired again. And at the command, they retreated on the double-quick only to get ‘backshot by the rushing Confederate soldiers.

Back shot

The rushing Confederate soldiers

Gen. von Cilsa stood a short distance up the slope, commanding, “Cease firing; they are our friends.”

David ran up to him and said: “No, General, they are the enemy, and they are charging in two lines.”

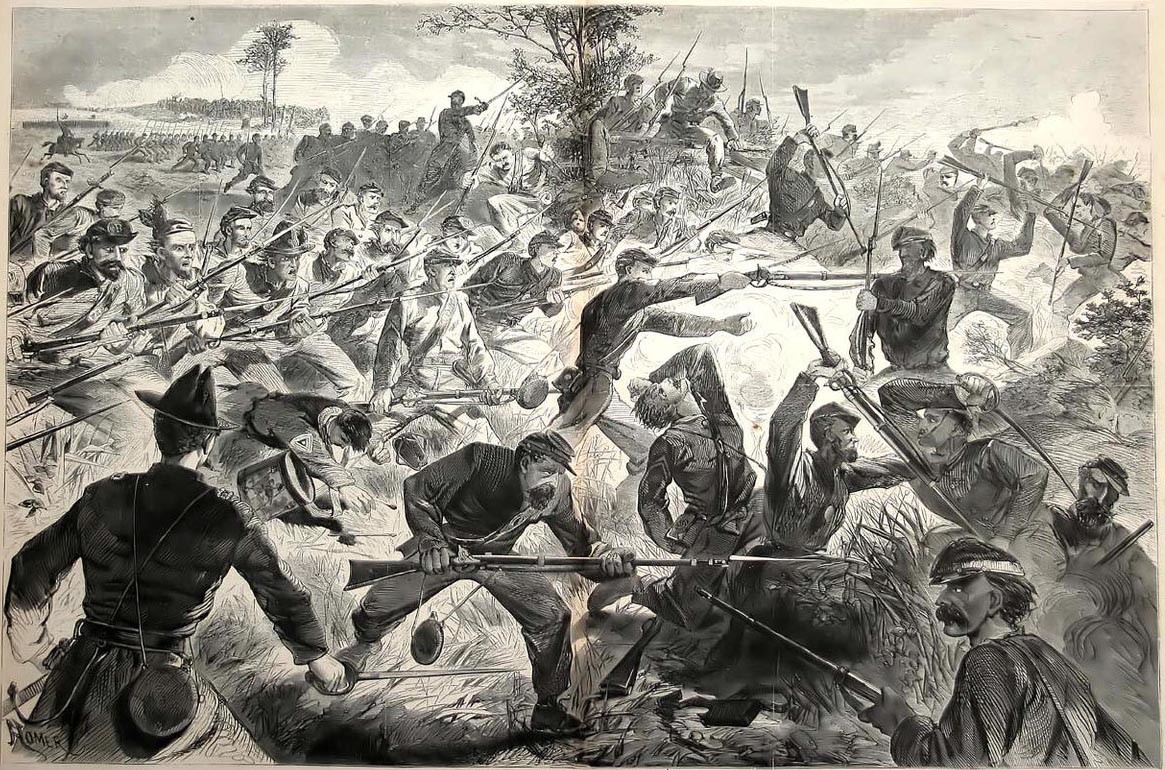

Hand to hand

When David got to the spot where his company had rallied, the fight was on in all its fierceness. Muskets were being handled as clubs. Men tore down rocks from the wall in front and threw them down, smashing into the bodies of the advancing troops. At times the fighting was so close only fists and bayonets could be used. Each man could feel the breath of the other man trying to kill him. This battle was so traumatic to David that it was a while before he could write about it in his diary.

No date:

I remember distinctly of seeing a rebel color bearer, with his musket in one hand and flag in the other, with outspread arms jump upon the stone wall, shouting “Surrender, you damned Yankees.” In an instant a company A or F man, I could not tell which, as the smoke was commencing to get heavy. I ran my bayonet through the man’s chest and firing at the same time.

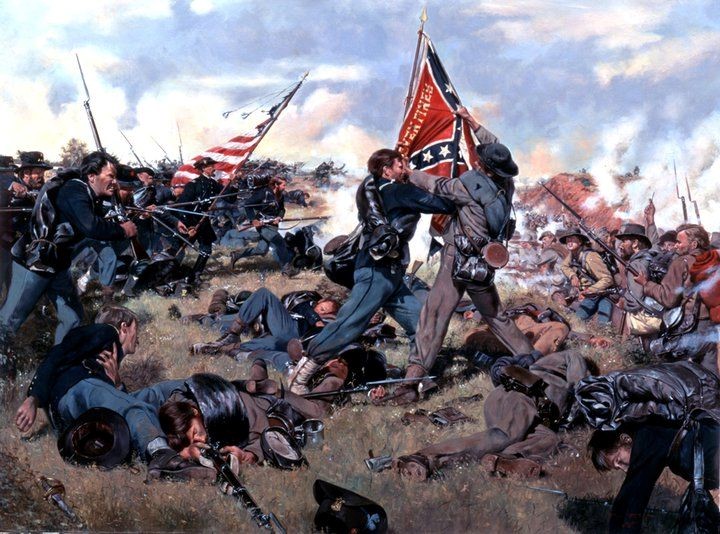

Fighting for the colors

I can still see in my mind’s eye how the shot tore into shreds the back of his blouse; as he fell backwards holding to his musket and colors, part of the flag staff was on our side; someone grabbed it while some one on the other side got hold of it and the tussle was lively for a few seconds, who should get possession of it. I think the Rebs must have gotten it, as I never saw or heard of it afterwards.

The 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteers on Cemetery Hill

As David was retreating, he noticed Lieut. Yeager, who had gone down with a terrible wound having been shot through the hip. He was urging his men to withdraw, or they would be taken prisoners. A moment afterward, a rebel shell passed in front of David, and the swing of its fuse struck him across the face leaving a black powder burn. Meantime David thought of home and friends, but he remained ready to shoot every Rebel in sight.

Confederate charge up Cemetery Hill

All the straggling soldiers finally landed on Cemetery Hill behind the stone fence. One of the men shouted, “Let them come now. Shoes or no shoes, we will let them know that we are here.”

After being behind these fortifications for a while, David saw the Rebel skirmish line drawing out on their right. Orders came soon for them to go down and meet them, which they did in the fields down below Cemetery Hill.

Confederate soldiers stripping fallen Union troops of clothing

On the slope of Cemetery Hill, David saw many dead soldiers whose pockets had been turned the wrong side out. They had obviously been searched, and their valuables had been taken. Most horrifying were the bodies that the clothing had all been torn open. He could tell when he saw blouses unbuttoned and even trousers pulled down; this was done by the dying man himself looking for his mortal wound. His body was left as a testimony of his last minutes, and David could tell how he died by the expression still life-like on his face. This was a common sight after a battle.

The next day while on the skirmish line, Lieut. Barnes and David were standing under a small tree and discussing how soon the Louisiana Tigers would charge them. They had been discovered shortly before sunrise, lying in a depression in the ground at the front. About this time, something came sailing along through the air just between the two men that did not have the familiar sound of a shell.

The Lieut. remarked, “I think that must be a piece of iron” As it passed through the treetops, it broke off a limb about an inch thick.

When the branch dropped to the ground, it knocked Barnes’ cap off. “I think it was iron, boy,” he remarked, “And the next thing they will be throwing blacksmith shops.”

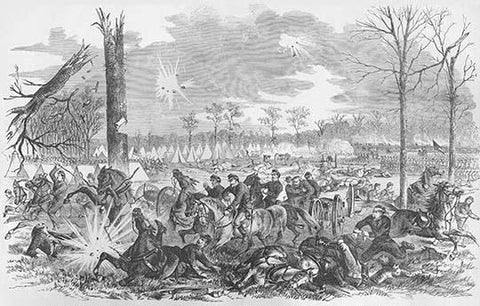

As expected after sundown, along came the Tigers with many others charging in two lines deep. Sometime later, David wrote about it in his diary.

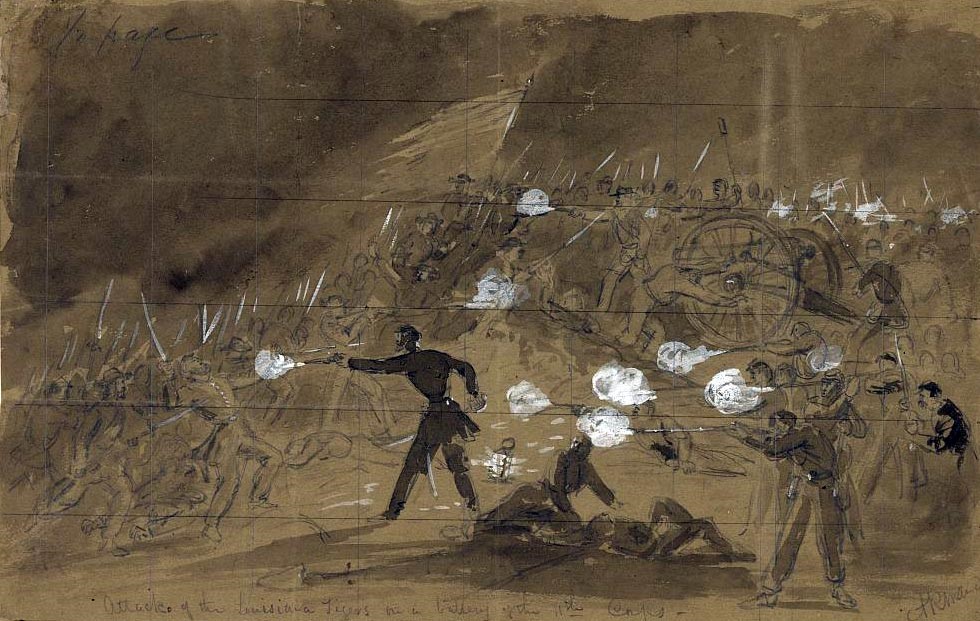

The Louisiana Tigers

Confederate attack by the Louisiana Tigers at Cemetery Hill

The area of the Confederate assault on Cemetery Hill not long after the Union battery repulsed the fierce attack by the Louisiana Tigers

No date:

In the evening of the first day, I had charge of a detail of men before the cannon. We remained in this position protected as well as we could during all night of the first day and until the evening of the second day. Up to the time of the charge by the Louisiana tigers on the evening of the 2d, we were associated with a skirmish detail of the 33d Massachusetts. After the charge was made and the enemy repulsed, we followed them down to the stone fence and lane. Here we remained on these low grounds until the 4th day.”

The stone fence and lane

David had taken the only option for a safe position at that moment, and it was behind the stone fence. He laid his rifle resting between two stones so he could fire whenever a rebel popped up out of the tall grass or from behind a tree. That was how he could pick them off when the opportunity came. He was just in the act of firing when a ball hit him in the left knee. He, of course, ceased firing and lay down and took in the very sorrowful situation for him.

David felt helpless and unable to move. Then he prayed, “Dear Lord, help me.”

A tear came to his eye, but he brushed it away as he took out his mother’s handmade scarf from his haversack. He tied it around his leg to stop the bleeding. It was soaked with blood right away.

The overwhelming Rebel forces drove their comparatively thin line back. David lay on the ground at the extreme right of the line with a bullet wound through a knee joint. He watched, with mingled apprehension and pride, the stubborn retreat of his regiment.

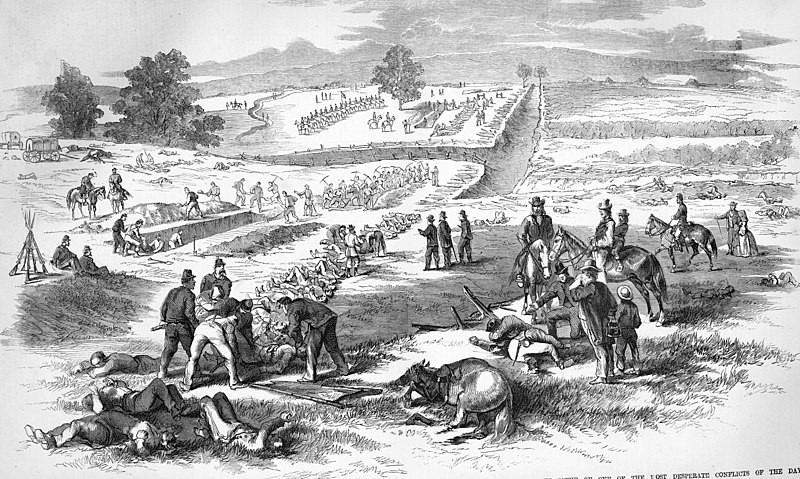

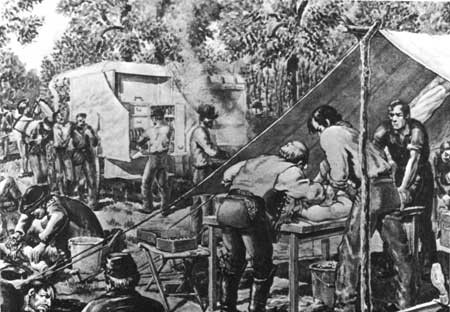

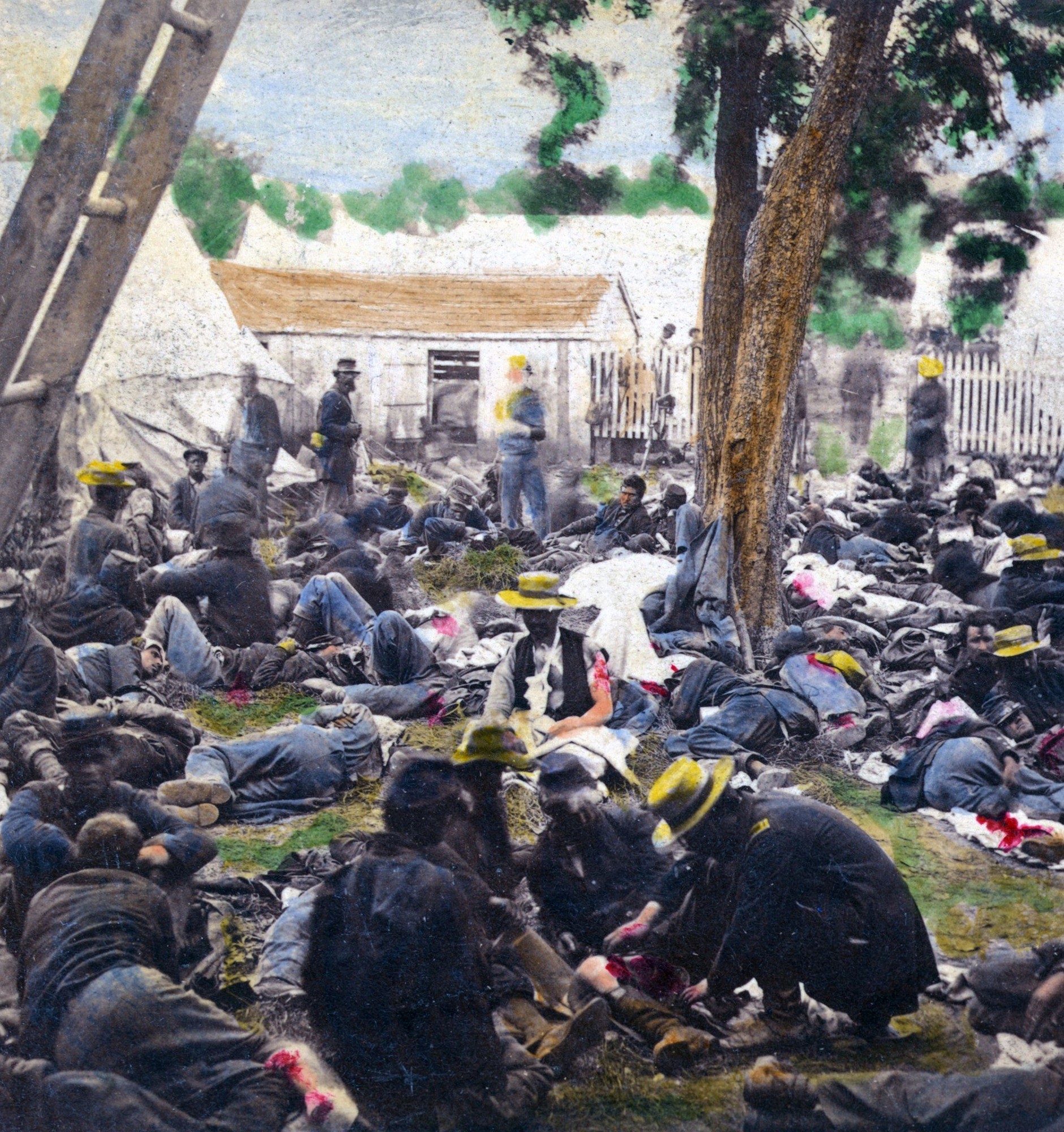

Removing the wounded

Lieutenant Barnes, commander of the Company, at that time came near where David was lying. He told him quickly the condition he was in as there was no time for a long story. Barnes sent two men to carry the wounded man from the field and away from danger, which they did willingly to get away from the fire themselves. They took David up to Cemetery Hill across the road and laid him down in some grass. Then the two comrades who were so kind to him vanished. There was no time to thank them for their kindness.

Medical help in the field

David looked about and learned that he was lying in a graveyard, the old Gettysburg cemetery. Soon, however, an ambulance came along, he was taken up, and the horses were driven as fast as they could go. He was lodged on the threshing floor of a barn that the eleventh Corps used for a hospital. They laid him down near the big door where David had an excellent view of the bursting shells coming in his direction. It was at the time of Pickett’s charge. Suddenly there were six explosions of shells in one moment!

Pickett’s charge – third day of battle July 3, 1863

Indeed, it was a grand sight, but the danger was becoming so great that every man was removed from the barn except David and an old German. Speaking German, he expressed himself in words that David did not understand but he had heard before. Then the man exited the best way he could, using a mop for a crutch.

Hospital tents

The surgeon, who had been in shortly before looking after the wounded men, ran for his life with his coat tail standing straight out. As he passed the door, he called out to David, “Get out of here as soon as you can.” At the same time, he knew that David could not move.

Make shift hospital

The surgeon soon sent two men to carry him away, which they did. They placed him in the lower part of the barn, in a building called a wagon shed. Wounded Rebels primarily occupied this place. He was now out of sight but not out of danger. These fellows were his company for two hours, arguing for their cause, and David for his.

It was a real blessing from God that David had been put among the Rebel soldiers in the battle. The Union lines were very fluid and crumbling in some parts, and buildings and places of refuge were prime real estate to foot soldiers. So, it was to no one’s surprise that the barn where the hospital had been set up was the first structure the advancing Rebel forces approached.

The first two soldiers entered the wagon shed and pointed their bayonet-mounted rifles directly at David’s body. “Yawl’s captive prisoner now; we use you-all for the ex-change.”

All captured men, including the wounded, were being immediately sent off as prisoners of war to be used for the exchange of their soldiers held in captivity.

Rebel soldiers taking cover

Then what happened next can only be one of the many miracles that did happen during this struggle of liberty between free men to set other men free. All the wounded men in that room had shared a near-death experience. Not only their personal wounds, but they had seen and witnessed the trauma of others. They were all under the same cannon fire. And there was no way of knowing whose shells were falling all around their perimeter. They just knew that each one of them could die in a flash. This is the bond of brothers in combat.

One long fight

Unless one has been there, one will never experience its holy power to make all persons one. The rebel soldiers had the time to listen to David’s view on being an American. Even though there were many differences between the two opinions, each rebel soldier overcame them. In addition, they moved to stop their own men from approaching David in any way.

The only comment they made was, “This Yankee is one of us.” So, none of the soldiers who entered that room challenged them, for they told everyone the same thing.

David wondered about his tentmate Chunky. Where was he? How was he getting along? There were few men in the regiment with whom David was better acquainted, especially in earlier life. Chunky was a man of striking presence and friendly spirit and manners. He made friends and held them. He took great pride in everything that pertained to his Company. He was deservedly popular with his men. Many of them have known him from boyhood.

David laid back, closed his eyes, and said a little prayer to the Lord. He asked him to watch over Chunky, “Please Lord, keep him safe from all harm. And Lordy, if he gets himself captured like I did, I pray that he will be treated with kindness like these men who surround me now.” He did not open his eyes until the sounds of the morning could be heard.

The wounded

Lying in this same spot until the afternoon of July 2nd, David was then removed to the Poor House. No room was available there—the place was filled with Rebel wounded—he was put down in the yard, near the driveway. Shortly before noon, a Rebel signal corpsman got up upon the roof of the Poor House and started to signal the Confederate Army.

Then began a terrific cannonade from the Union forces in their efforts to dislodge this fellow and stop his signaling. The shells passed over David’s head and landed in the garden nearby. He thought about the onions Chunky and he had stolen the day before. But now, all that was left of someone else’s hard work was a smoking hole in the ground and the smell of gunpowder.

Union guns

Judging from the effect upon David’s wound —each crash was like singeing the leg with a hot iron. He imagined the suffering of the wounded in the Poor House must have been terrible. This torture had continued for some time when a bright young Confederate officer passed by.

David called his attention to what the corpsman on the Poor House was doing, adding that he thought a hospital was not the place for a signaling station. To the young officer’s credit, be it said that his face flushed with shame at the action of his comrade in arms. Drawing a revolver, he pointed it at the Rebel on the roof. And with an oath, commanded him to come down or he would kill him. The fellow complied in a hurry, and the firing that had been directed upon the Poor House ceased at once.

Comrade Doll lay wounded in the left shoulder right next to where the Rebels had laid David down. He said he had been brought there in the morning and left for dead.

Mr. Doll was sad that his friend James had been removed for burial, “How sad that we were within a mile or two from where he was wounded, and I could not have been with him, to at least pour cold water on his wounds. James was a good boy.” Not thinking of himself at all, the man died.

Field hospital

David tried to make himself as comfortable as he could. He was cold and reached for his haversack, but it was gone! Where did it go? Did someone steal it? Where did I leave it? These thoughts went thru his mind all at once! When did he last use it? He could not remember. When did he last see it? He was not too sure. Did it get left where he was wounded? He thought that he had it with him up until now.

“Oh no,” David said aloud when he realized what was in the haversack, his Bible with the diary inside.

He felt down his leg to the knee, and his mother’s scarf was still there. It was loosely tied, but the dried blood kept it in place. It was a badge of honor. At least he still had that. David could feel a deep hole in his stomach, and he felt a little faint.