Another soldier’s story

Chunky had his plans all made up before he enlisted with David. He wanted to become a doctor and the war could be his stepping stone right into medical school. When he was not practicing or playing in the company band, he volunteered to work in the hospital. His large statue in size and character was a blessing to all he worked with. His handle-bar-mustache was always supported by his big wide smile. Somehow, he was able to find some good everywhere.

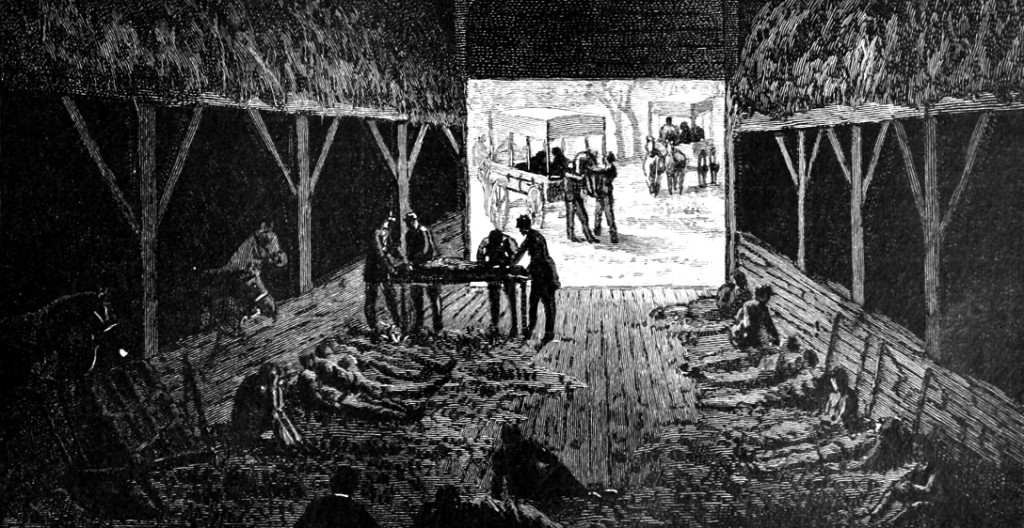

a Union field hospital

a Union field hospital

He gave very special care to the wounded men. Chunky had earned the doctors trust and respect through the many hours he had worked directly together with them. There were 24 men of Company D wounded and 7 killed. Chunky was acquainted with all but two of them.

a battle field hospital

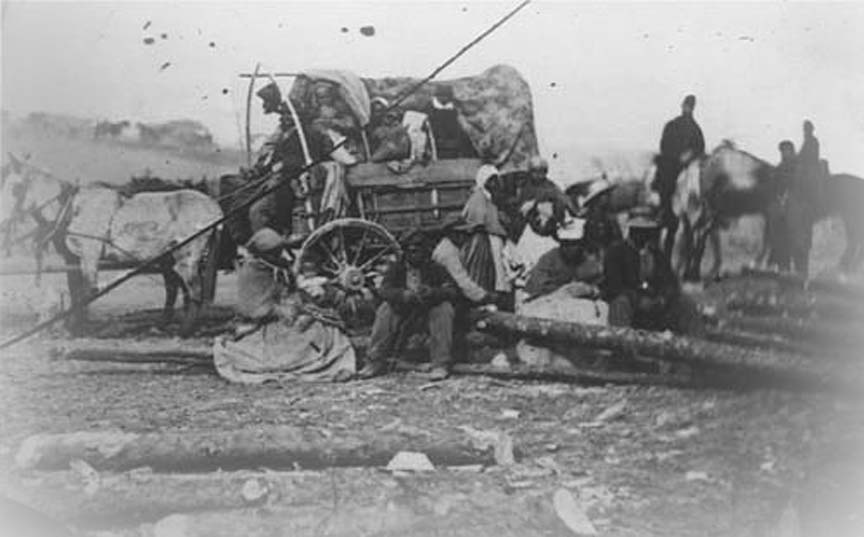

War does not take all the victims with a gun. Hunger, disease, lack of clean drinking water, and infections kills more soldiers than bullets. Chunky was one of the men who foraged for corn at the time when men and animals were destitute of food at the encampment of Stafford Court House.

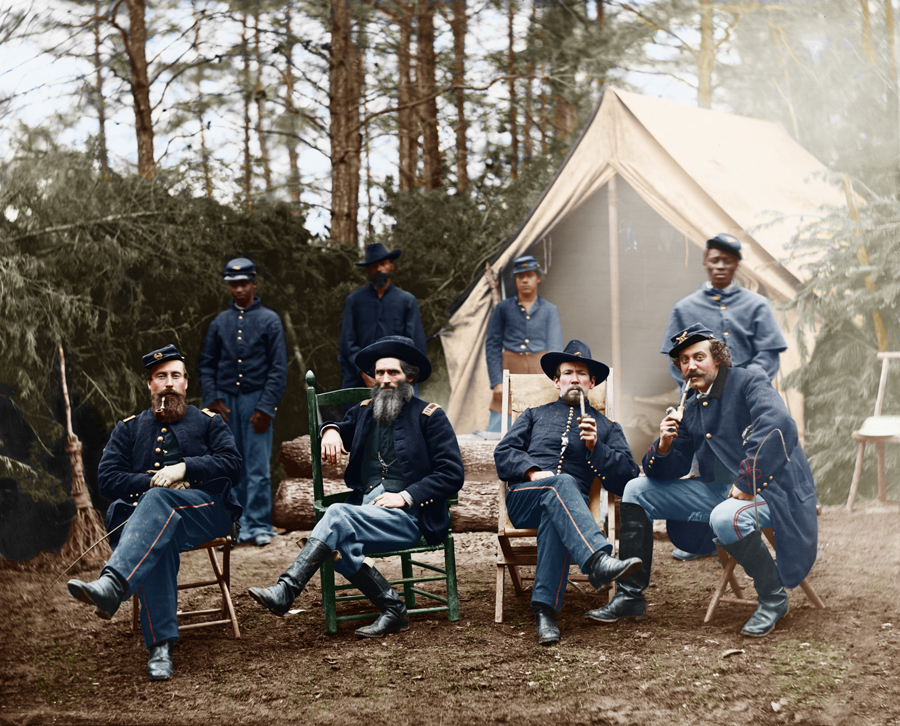

Stafford court house

Chunky remembered a sad case of a soldier who in great desperation for food asked permission to eat corn from the mess the teamster was about feeding to his team. The man ate so ravenously of the raw whole corn that in three hours he died from the effects. Chunky also remembered an incident of men in a half-starved condition eating meat taken from the head of an animal which had many days before been killed for food and just the skeleton of the carcass was left.

the wounded

While Chunky was around the hospital, assisting in the care of 1500 wounded, he strolled out back of the barn. He wholly unexpected found his friend John lying under a shelter of a few boards which had one end laid on a fence. It was alongside the barn. He was very glad to see Chunky, and his case was pitiable enough. He had been wounded in the chest, and a great profusion of blood had saturated his clothes, pocket book and all. John requested that Chunky send his money home. There were $60 in bills so covered with blood that they required soaking and washing. He laid them out on the boards, with some pieces of garments, also, to dry. Sergeant John Seiple died of his wounds. He was in the ward of the barn and died near where Chunky was in attendance. He suffered intensely from lockjaw, and when Chunky saw that he could not live he thought death was preferable as he witnessed him breathing his last. Chunky wrote his family a short letter. And along with John’s life savings this was all that went back to his home.

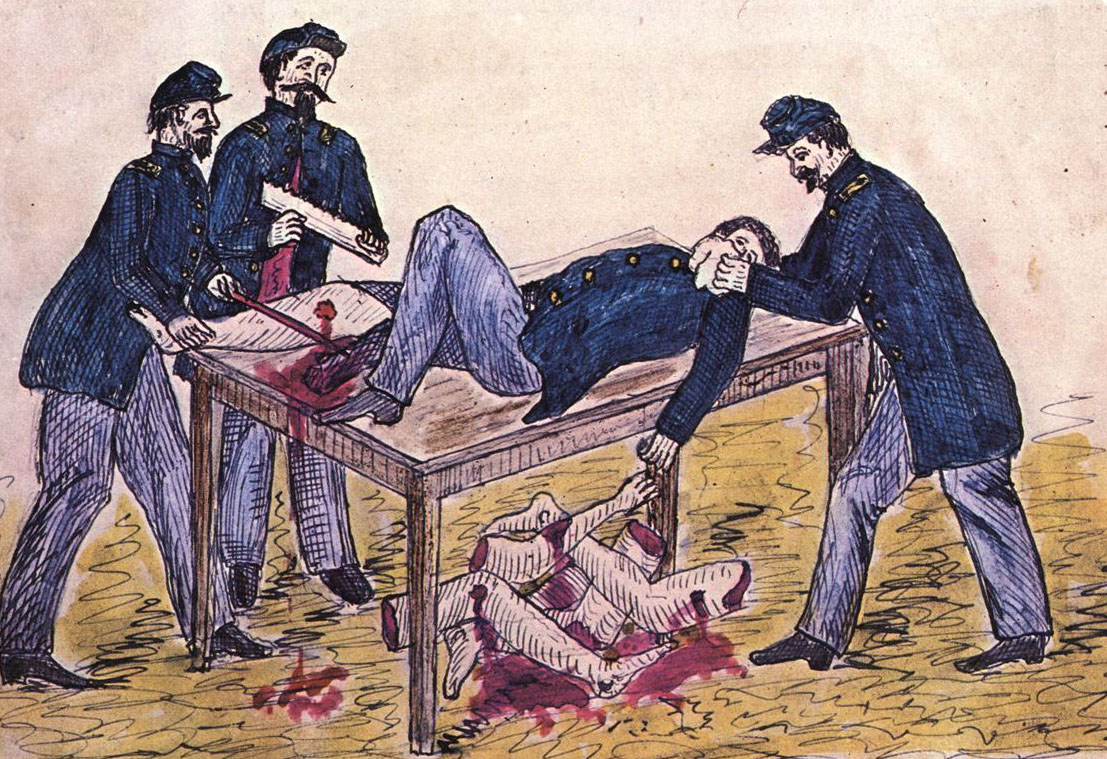

Civil War medical chart for amputation

When Chunky was not on duty playing in the band, Dr. Neff was teaching him nursing in the 9th Corps hospital. Chunky told the men often, “I carried Dr. Neff’s instrument case in and out of battle, —carried it out more rapidly than I carried it in. I did it successfully, however, by making good use of my legs.” Dr. Neff felt that it was necessary for Chunky to learn all he could from him, so he could become a good doctor someday. Combat surgeons learn very fast about human suffering during war. Chunky witnessed and helped assist holding men during too many amputations of arms and legs. The remains were stacked like cord wood outside the hospital barn. No one would shake their hand or kick them anymore.

stacked like cord wood

During a heavy rain storm, Chunky spent a night of the most awful heart strain that he had ever experienced. A young soldier lay under the eaves of the barn during a torrent of rain with, but slight covering, surrounded by hundreds of others. His cries for help were truly the most heart-rending one could listen to. His shrieks became unendurable. Chunky hunted about to learn from what direction the calling came and finally found him under some boards which had been hastily laid up for shelter.

giving comfort to the dying

Chunky asked him where he was wounded, and the man could not tell, except that he had great pain between his shoulders. With great care, he removed his shirt to ascertain the location and character of the soldier’s wound. By the dim light of an old lantern he succeeded in finding a battle injury between the shoulder-blades.

stabbed in the back

It had the shape of the incision being exactly that of a bayonet. From the size of the hole the weapon must have pierced deeply into his body. The man died shortly after. His silence was a deafening reminder that life can end in an instant.

death comes slow

Cherries were ripe and very plentiful in this place, and the boys did not object to, “pick cherries.” Chunky and a couple of men took a walk through the trees staining their fingers red with juice of the fruit. As sweet as the cherries were to the tongue, the red color was not so pleasing to the eyes. It reminded them of something else red all over their hands. No one said anything but they all knew what each other was thinking.

Later that afternoon Chaplin Melick came in camp with a great loaf of bread about seven by sixteen inches. He had also scavenged three pounds of fresh butter. Chunky asked him where he got them, and he said he bought them. The men wondered where did he get the money, for they knew he had none. He answered that he borrowed it. They never found out how he came by it but of course they had their own opinions. Still they never believed that any member of their mess would take anything and not pay for it or at least promise to pay. Chunky told the men, “Let me state right here, that was the best bread and butter that I ever ate.”

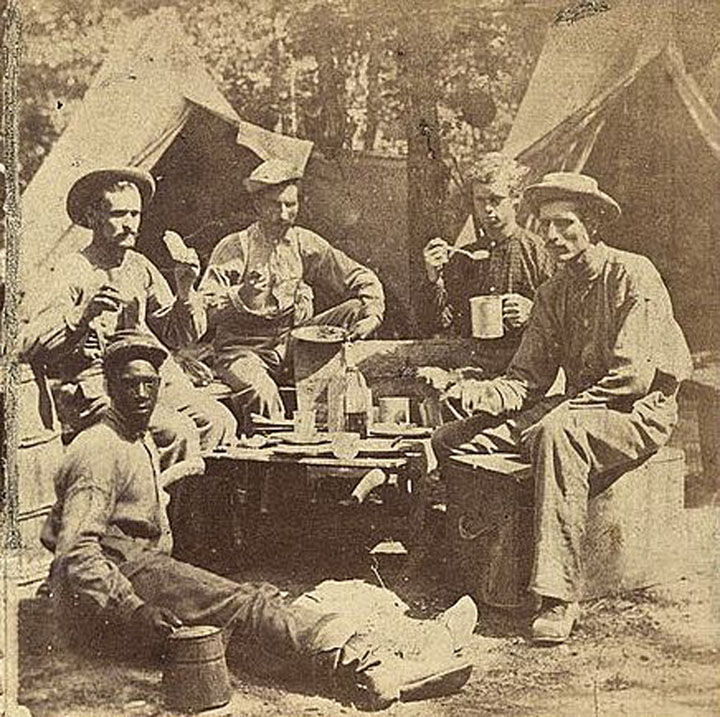

time to chow down

The Chaplin told the men, “I believe two-thirds of the boys would re-enlist.” He did not know if he would go home at all. He said that he thought, “the matter of the war could have been settled by peace measures.” But now he believed the South did not want peace. Dr. Neff playfully said, “The Chaplin is all right, but he is a Democrat.” “Yes,” said the Chaplin, “but I am not a Copperhead.”

cartoon about the Copperheads, published in Harper’s Weekly, February 1863.

In the 1860s, the Copperheads comprised a vocal faction of Democrats in the Northern United States of the Union. They opposed the American Civil War, wanting an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates. Republicans started calling the anti-war Democrats “Copperheads”, likening them to the venomous snake. Those Democrats accepted the label, reinterpreting the copper “head” as the likeness of Liberty, which they cut from Liberty Head large cent coins and proudly wore as badges. Democratic supporters of the war, by contrast, were called War Democrats.

Copperhead badge

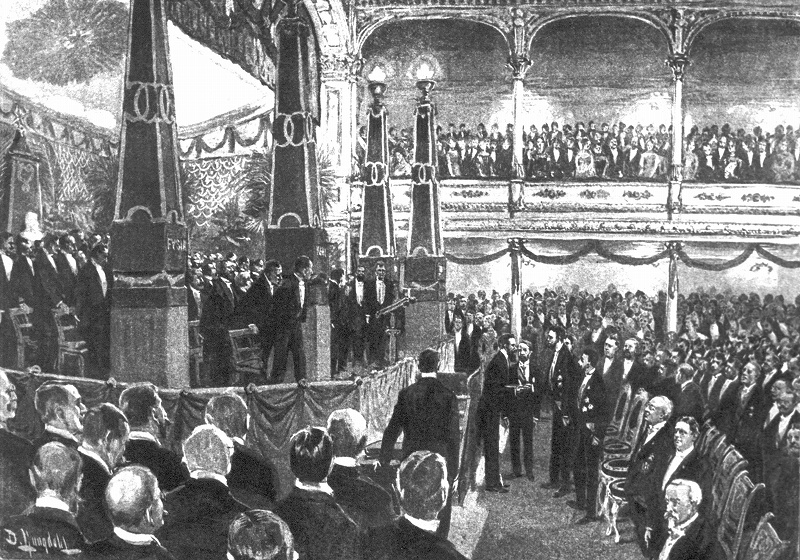

In accordance with the wishes of Chaplain Melick the men built a temporary enclosure of logs and pine boughs around a tent, for a chapel service. They fitted it up in good style and called it “Chapel Grove.” They held their first meeting in the new church, May 29, 1863. On the evening of the 31st, General O. O. Howard attended the meeting and made an address which greatly encouraged all present. The company band played and Chunky sang an old hymn. His voice was loud, and heard by all listening, as something of beauty in the middle of a real big ugly.

chapel grove

After this Chunky met with the Chaplin and he was very anxious to know how he was getting along. As the water in the canteen had given out and Chunky was very thirsty, he told him that, “water was scarce and hard to get, and I thought a great big drink of beer would be a good help to move a fellow along.” He was thinking of his father Jonah’s good and fresh, German brewed beer back home. But instead of agreeing with him, Chunky lost the friendship of the Chaplin as he turned his back and walked away mumbling something to himself.

ah.. fresh German beer

One evening an incident arose over the Chaplin’s refusal to take a social glass with the officers, who, along with him, had been invited to the Colonel’s tent. As the drinks were served, a custom which was popular among the officers, the Chaplin refused to accept the hospitality extended. Whereupon he was invited to take a glass of water. But this he also declined. His reasons for declining were sufficient, but apparently provoked resentment. No one wanted to argue among themselves, it was hard enough fighting the enemy. They all agreed that the invitation was an act of courtesy, and the refusal was also proper.

act of courtesy

At this time the regiment was still on the South side of the Rappahannock. The crossing was at the United States Ford. Chunky assisted in carrying the wounded across the river. A very heavy rain fell toward evening.

moving wounded across the river

He was all day of the 6th on the road with the ambulance loaded with wounded. They arrived at Brooks Station Hospital and he remained with them that night. The hospital joined the band tent. Chunky changed his rolls between nurse and band member as quick as duty called.

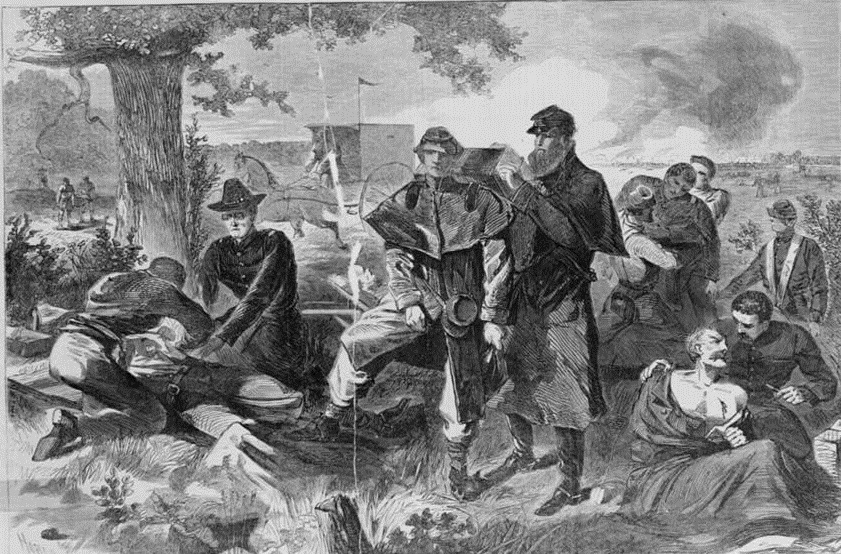

removing the wounded from the battle field

The removal of the wounded from the battlefield began on the 4th, a temporary hospital having been established in a brick house on the left side of the road from Chancellorsville House to United States Ford. May 17th, Sunday, on this day it was reported that Stonewall Jackson died last Sunday. The intelligence reached us through Dr. Junkins from a neighboring regiment. The doctor was a brother-in-law of the deceased.

Stonewall Jackson

There was a man in the Company who thought he was sick. The rest of the Company thought he was playing off sick, and was trying to get into the hospital off duty. He was a regular out-and-out hospital bum. He reported to the doctors, was examined, and came back to the Company with a gun and a cartridge box ready to fight. The doctors had treated him with Blue Mass which was a dose of, milk sugar, rose oil, honey, and one grain of mercury. This concoction guaranteed a sure fire case of the, “back yard trots.” This treatment was enough to cure up any man in short order. Chunky chuckled to himself, “well the fellow got a great send off, and made himself scarce in a hurry. Near as I can tell, he was cured.”

Comrade Hess was struck by a minie ball above the knee. The ball went straight through, carrying the bone away with it, and splitting the bone as it crashed through it. He was lying in a little tent and apparently unconcerned, and without pain. When Chunky found him he said, “Well, you must go to the hospital, to the Operating table, to have your wound examined.” Chunky had hoped the ball had gone around the bone, but it looked bad. The holes were opposite each other. Comrade Hess was afraid to go to the- table for fear the surgeon would take off his leg, perhaps unnecessarily, so he wanted Chunky to speak to the surgeon about it. He cheerfully agreed to do so.

The doctors were busy in probing for balls, binding up wounds, and in cutting off arms and legs, a pile of which lay under the table

The doctor gave him the most hearty assurance that he would do no wrong to the patient. After placing the man under chloroform, he ran his little finger into the wound and taking a pair of pincers from his vest pocket he pulled out a splintered bone several inches long, showing that the bone was badly fractured, and in fact carried clear away. Chunky took a long piece of the bone and showed it to Mr. Hess to show him that the amputation of the limb was an absolute necessity. He seemed to be satisfied and the operation was performed.

About this time Chunky saw the actions of a man which he could not understand. The soldier had his gun on his shoulder, the line of battle could not stop him; the provost marshal could not stop him. Chunky saw a cavalryman strike at him with his sabre which barely missed his head. It being warded off by the gun barrel on which the blow struck. But this thing, in the shape of a man, did not wink or dodge, but marched through the guard as if there was nothing in his line of retreat. And for all Chunky knew he was still retreating instead of going to the hospital. What happened to this soldier was as old as war itself. The ancient Greeks called it, “Divine Madness.” During the Civil War it was called, “Soldiers heart.”

Brass band

Comrade William Taylor was wounded early on in the battle and he lay for two days on the field. He usually carried a horn, and played with Chunky in the band, but that day he carried a gun. He was picked up the third day by the ambulance corps and taken to the barn used by the Eleventh Corps for a hospital. Dr. Neff had loaned out Chunky to help them with removing the wounded men from the field.

Hospital barn

After the Chief Surgeon looked over William he thought there was little or no hope for him. So, the patient was left in the corner of the barn, alone, to wait for what comes next. He was just left there to die. That is where Chunky found him with a B-Flat horn case for a pillow, and his overcoat folded and placed under his head. A blanket was thrown over him.

But in the meantime, he had lost his coat out from under his head, and his blanket had slopped from him. Blood was running from the wound and from his eyes and nose. His lips were so swollen he could not speak. But he was conscious. Conscious enough to recognize Chunky’s voice. By prying open his mouth with a spoon, Chunky fed him some soup. It was the first food this soldier had taken since he entered the battle four days before.

Chunky went to the Chief Surgeon, told him of his friend William, and that it had been supposed he would die. Chunky was very voicetress and he was talking louder as he said, “But he did not die! And he ought to have medical attention now.” The Chief Surgeon went with him and looked at William and added, “…that is a very interesting case. He is a bright, strong fellow maybe he can pull through,” or a word to that effect. Chunky was not too sure what he had said. The Chief surgeon did not seem to be interested in anything Chunky said.

Chief Surgeon

All his life, Chunky easily made lifetime friends, out of anyone that took the time to meet and talk with him. His large size and big handle-bar-mustache made him look like a formattable character. But when he greeted all, with that contagious big grin, you were glad to know he was on your side. Jonah, Chunky’s papa, had always taught him, “do not to take advantage of your size of body but use your strength of mind.” From the time he was young, his papa had told him that his size could intimated anyone, but he felt it was better to have a strong educated mind. Chunky was just trying to communicate with the Chief surgeon on his level, but he would not let him.

The poor fellow had been lying there on the field, without food, drink or shelter. It had rained and the cavity in his head was half full of water. Dr. Neff afterwards told Chunky that probably the rain had saved his life, as it kept down the inflammation. Chunky calmly, and very quietly, asked the Chief Surgeon, “Sir, what should I do with this man?” He replied, “Put him wherever you can.” That meant a great deal, or it meant nothing, as every flat space was full.

Chunky got a stretcher and another soldier to help move him to a large tent going up about one hundred yards away. He remarked to his comrade, “I suppose that is an officers tent but the Chief Surgeon says we shall put you wherever we can.” They took the man right in and lay him down. Chunky thought to himself, “He is too badly hurt for them to throw him out, if they protest, we will tell them our orders.”

The officers tent

But the protest did not come from the officers in the tent. The Chief Surgeon could be heard, back at the barn, yelling at the top of his longs, “just were in the heck do you think you are going with that man.” Chunky stopped dead where he stood. The outraged doctor ran up to him and got right into his face, well at least up to his chest. The two men took a long stair at each other anticipating their next move. It came from Chunky, “Sir” he said, “Sir, I enjoy working with you because there is so much I can learn from you, that will help me become a good doctor someday.”

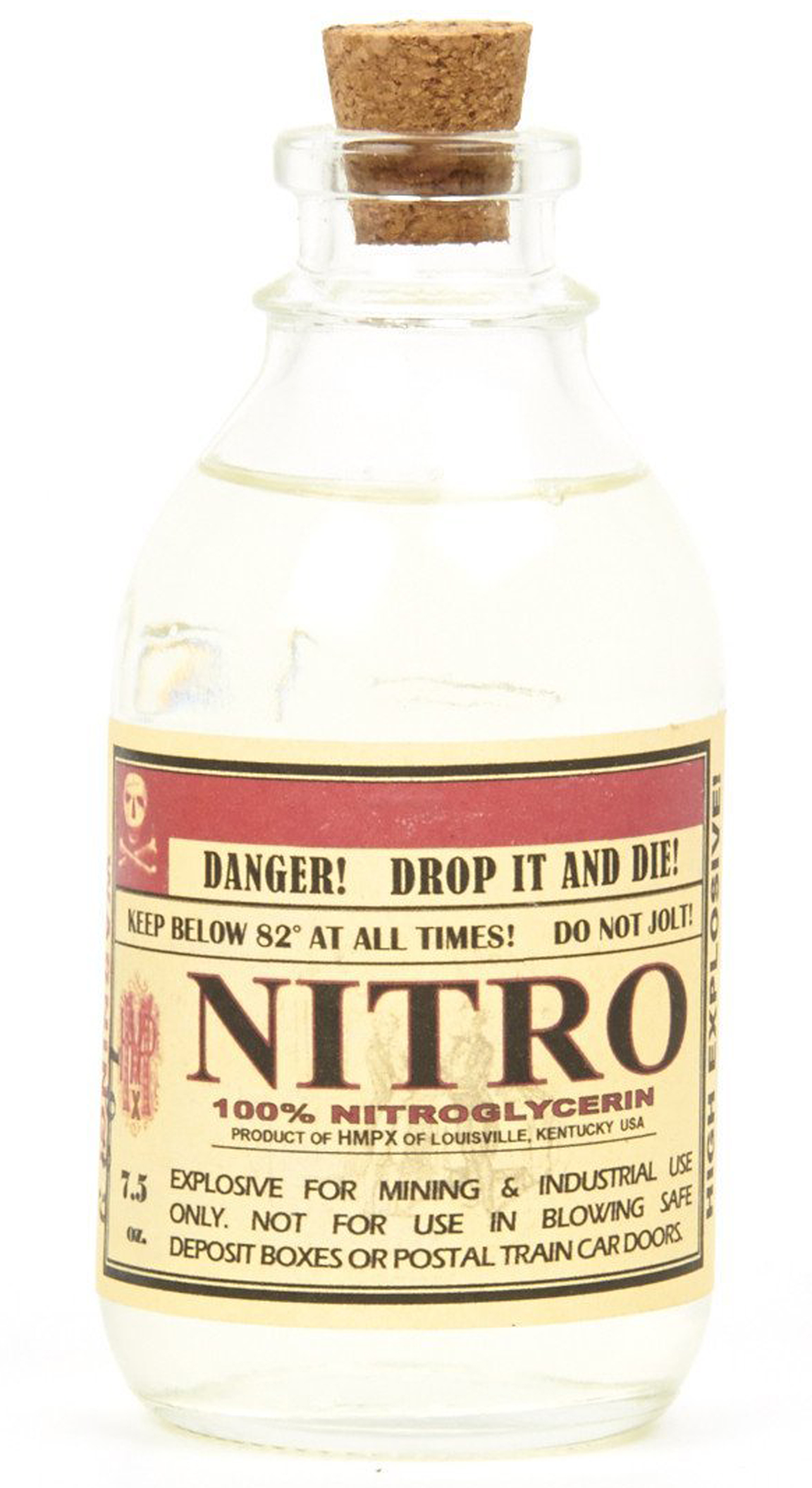

The Chief Surgeon shouted back at him, “You will never be able to do what you want. You certainly can’t do that. They will never let you into my medical school because you are BLACK.” Yes, Chunky was born, Charles Washington “Chunky” Godfreed, a black man whose parents were both freed slaves.

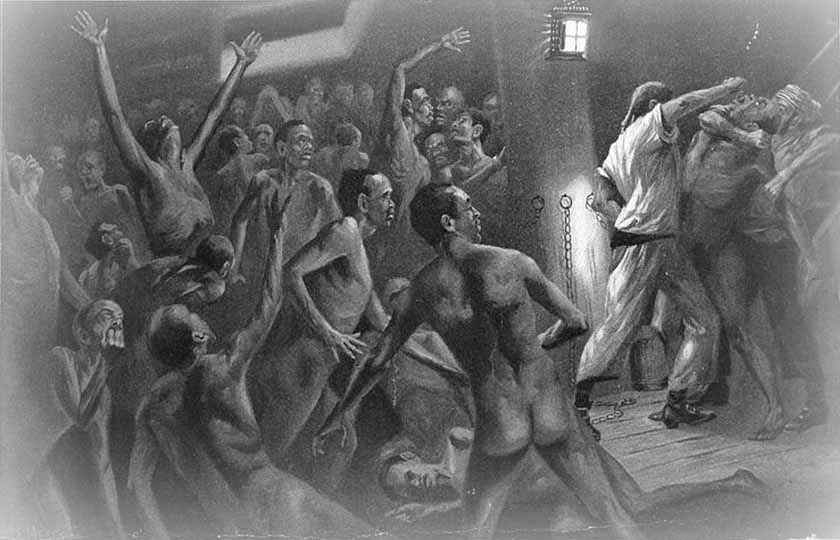

The struggle

Time stood still for both men. The Chief surgeon was not too sure if he was about to get punched. But all Chunky was thinking about was the stories his papa, Jonah, had told him long ago about when Jonah was a slave. He always told Chunky that he could be whatever he wanted to be, because he was born a free man. Then he flashed back to a memory from his childhood.

Part 1 Jonah as a slave:

It was the longest day and the shortest night in June. That day was particularly hot and long. All who endured it yearned for the cooler night time. But the darkness did not always promise a good rest. Because of a long and wet spring that year, the bugs this time of season were in command of the night air.

A fire was kept going all day and the smell of meat cooking over an open pit had been teasing everyone around for miles. The meal was served and all who enjoyed it were found to be, too full, to do, too much of anything. So, they all gathered around the fire pit to hide from the bugs in the smoke. Chunky made sure his father, Jonah, had a seat with a pillow on it and he placed him in the warmest spot, next to the fire. Most of the adults drifted away leaving the children camped out around the heat. Just a few hours ago they were all too hot. Now the night air had a little chill, so they grabbed their blankets, and set as close to the fire as they could without getting burnt. They had to keep rolling around like a pig on a spit, to keep all sides warm but not toast their fanny.

It was a voice heard from under a blanket that first broke the silence. This was what they all did in the summer next to the fire. They talked. They talked and listened to each other. They always had an interest in what someone else had done or experienced that day. This was a curiosity about someone they loved, their family. And you could share your feelings openly, without fear of being shamed. This was truly a safe circle around the warm fire.

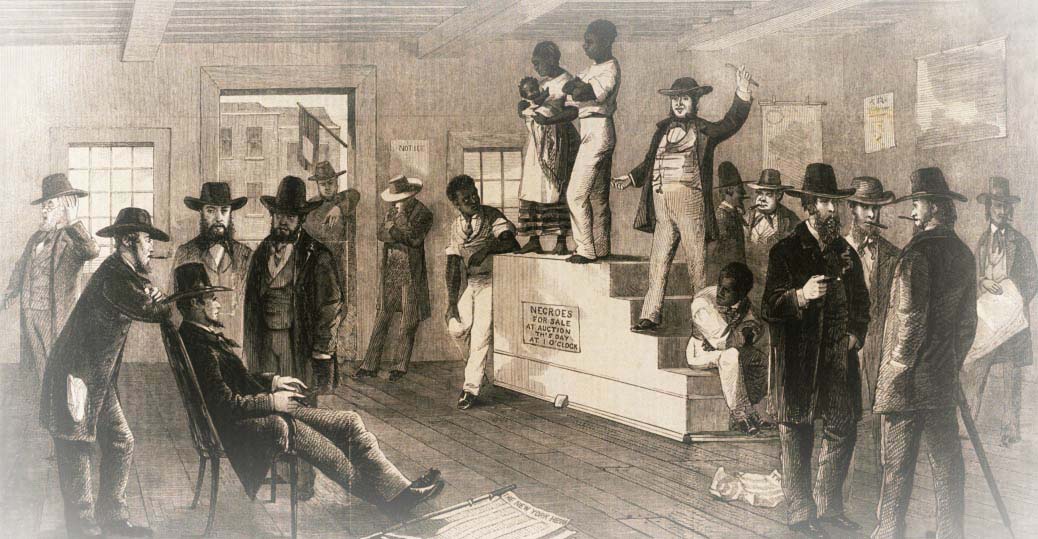

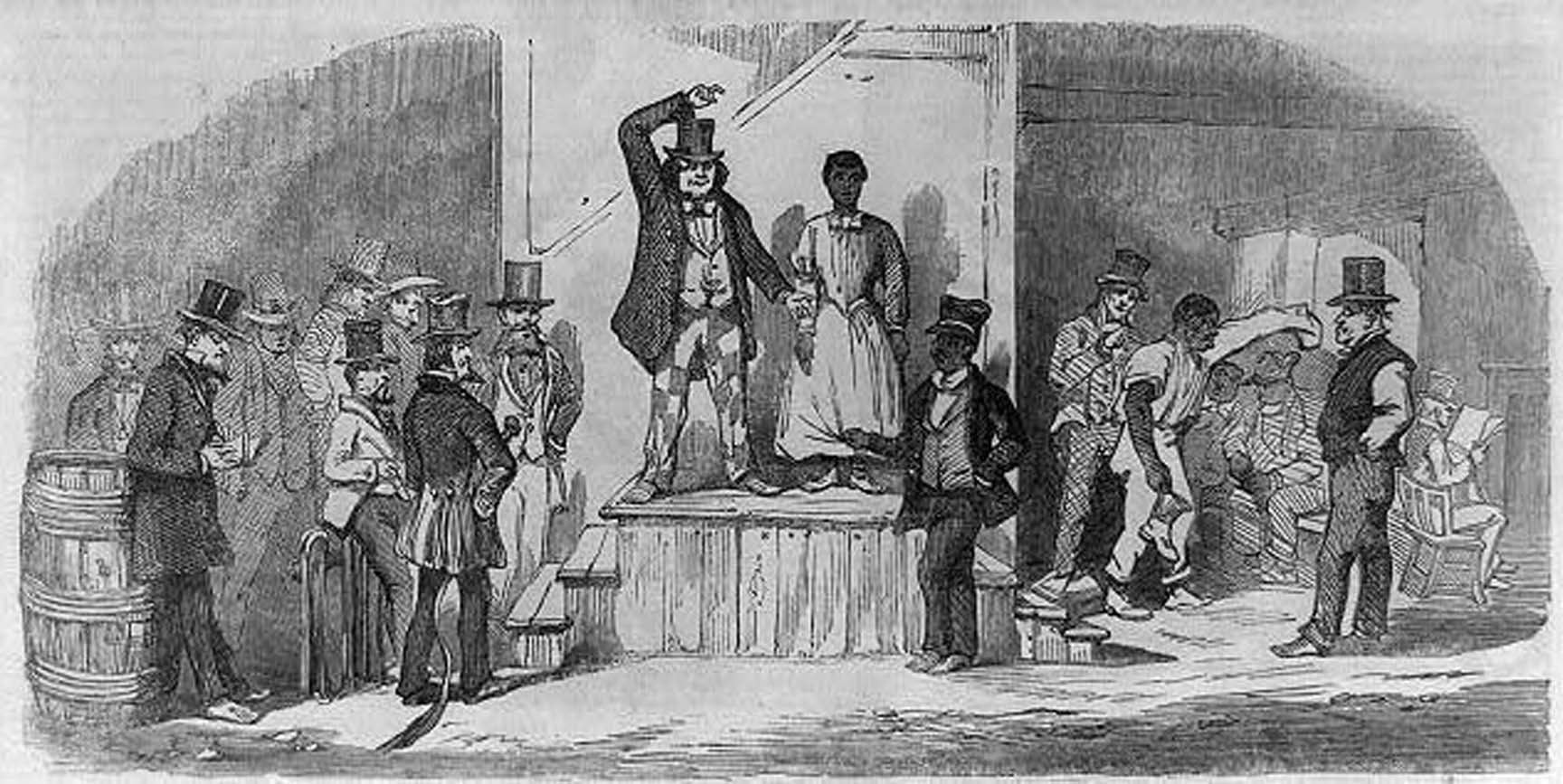

Jonah was asked again, “Tell us, what do you remember about slavery times.” It took some time before he would let himself answer. His heart grew very heavy just thinking about that, far back time. “That ain’t far back enough,” as far as Jonah was concerned, he thought to himself. With a very gruff voice he shouted at the blanket person, and he growled, “The highest bidder gets you. He’ll carry you to his plantation.” He snapped back, and pointed with his finger as if to show how far away that was.

Jonah said sharply, “Today I’s a freed man, can do what I wants.” Jonah hit on his pipe, gave a little spit, and continued, “Back then they’d, put another on up there, Me highest bid.” He pretended to be counting money when he told those listening to him so intensely, “whichever one bid, gives the most, he carries you to his plant, that the white, in the South.”

As the flames from the fire begin to die down a little, he mumbled to himself. No one understood what he said and after a while he repeated himself. It got real quiet and it seemed like even the crickets and frogs were giving the story teller 100% of their attention. You could feel the pain in Jonah’s voice as he quietly spoke. “And they went to mistreating the, the colored. Getting children by the colored women. And all such as that, gett’in da colored.” For someone that usually kept his thoughts to himself, this sudden eagerness to talk was out of character for him. The family had tried in the past to get Jonah to share his life experiences as a slave with them. They only knew him as a freed man. He never talked about it before.

“Now I tell you when slavery…,” he paused long enough to reach inside his shirt for some more tabacco, “…way back in slavery time, I was a good size boy then. That’s when me young.” Jonah stretched out his arm and held his hand so high, then raised it a little. “Well my old master, he bought one, two horses, and Jonah. Now he took us all down to da farm, I recollect all of that. I was a big, big boy then. A good big boy. I’s remember my old master place. I’s remember he was a speculator. I’s remembers it, me was good big boy then.”

Then he stopped, and gave great care to his corn cob pipe as he emptied and loaded it with fresh weed. The two of them were great friends and they gave each other comfort and conversation when nobody else was around. They now held a captive audience that eagerly waited for what he had to say next. “He had a big old shed, dar. And he, and he had cotton all in that shed, and we boys would all go up and play in that shed every day.” Jonah could see that they were quietly listening to him with great respect for the story he was telling.

“And he had wagon, every, everyday he’d load up all them wagon and take all that cotton and go off, go off far. Now you see, that, that was in slavery time. I recollect just as well, and he’d bring back whole lot the colored people. The overseer, Black Adam say, master was speculator. And he sell them to all these people round this country. Him name just Adam, but we calls him Black Adam cuse he mean to other colored folks.”

Jonah wiggled his southern end on his seat as to resemble movement. “I recall that my old, my old papa was his wagoner.” He pretended to grab the rains and drive the wagon. He even made a snap sound as he showed how the whip was used. “I used to go, he used to carry me with him all the time. Used to haul cotton, carry cotton in that wagon.” He tried to take a puff, it was out, so he relit it. And took a big spit. “They’d carry cotton over here and weigh it up at a place they call uh, forgot that place name now. Carry cotton there and weigh it. I’s remember he used to be, he used to always work.”

Flexing his mussels to get a laugh from his sober audience he proudly proclaimed, “I was good, big boy at the time, and master had a oxen, had a old, had a oxen, had a old oxen name Steam Boat. That how come papa was his wagoner. And I’d ride old Steam Boat, ride old Steam Boat, drive the rest of them. My britches soaked with Steam Boat sweating on me. Ride him, till I get tired and get down, then walk side of them.”

“Well, old Steam Boat get tired, and just set down. Overseer Black Adam says get that whip, get on that, get this whip and get on it. As soon as Steam Boat heard that whip he gave out a big snort from the rear end and started off on his own in the direction of the barn with wagon, cotton, papa.” Jonah found someplace especialy deep in his heart and come up with a belly shaker of a laugh that was contagious to everyone. It continued until it was obvious Jonah was out of breath. Then again, very quietly, he said, “Papa die when I’s young.” The fire snapped a spark of life and he watched the ambers float up to the heavens. “That, that was in slavery time, that was old slavery time, it was. And I remembers. I can tell you some more bout slavery time.”

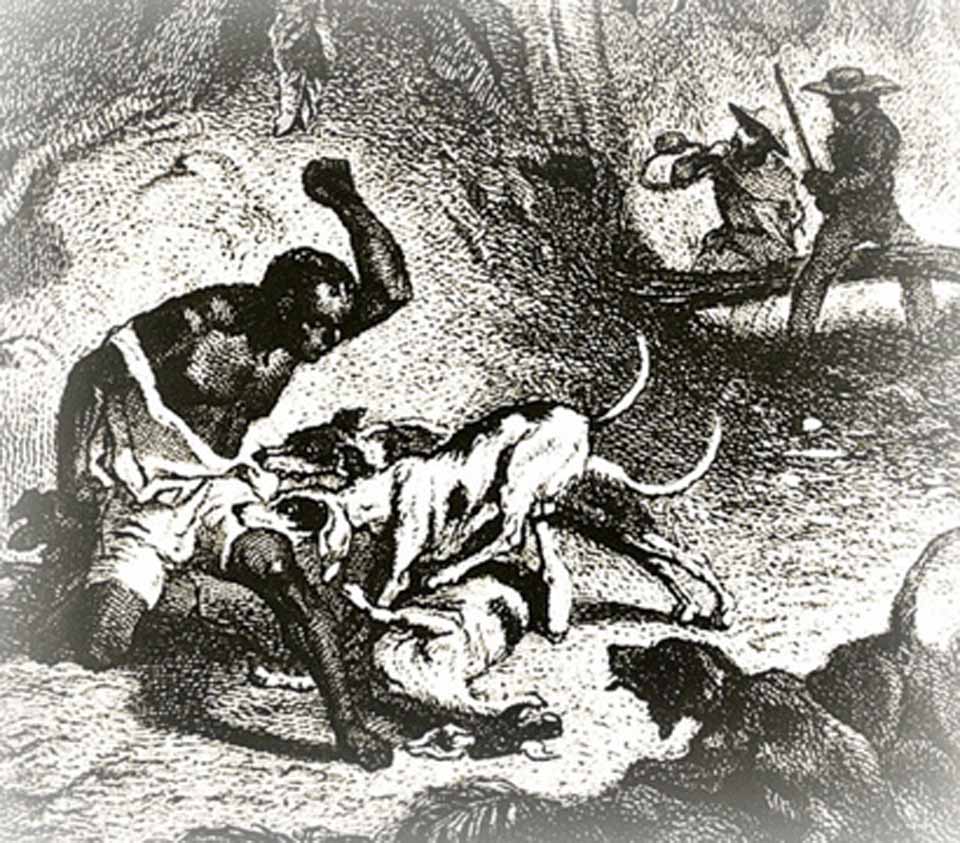

No one really used any words to give their approval of the oral history lesson. They all responded as if they were in church together, with a moan of, “more.” After relighting the pipe, but not taking a toke, Jonah smiled, showing he had no teeth left, he said “And was an old log jailhouse. And all around I recollect one time, we all was looking at it. And they, and they brought in, had hounds. And they brought them hound in and brought three colored with them hound, runaway colored, you know, caught in the wood.”

“And they, right, right across, right at the creek there, they take them colored and put them on, and put them on a log lay them down and fasten them. And whup em. You hear them boys hollering and praying on them logs. And there was a colored whup them. He gets whup his self if not do bad enough. Then they take them out down there and put them in jail. No one, no tell, what take place with them colored after. I don’t know, to tell you the truth when I think of it today, I don’t know how I’m living. None, none of the rest of them that I know of is living. I’m the oldest one that I know that’s living.”

“But, still, I’m thankful to the Lord. Now, if, uh, if the overseer wanted send me, he never say, you could get a horse and ride. You walk, you know, you walk. And you be barefooted and collapse. That didn’t make no difference. You wasn’t no more than a dog to some of them in them days. You wasn’t treated as good as they treat dogs now. But still I didn’t like to talk about it. Because it makes, makes people feel bad you know. Uh, I, I could say a whole lot I don’t like to say. And I won’t say a whole lot more.”

The silence of the audience was interrupted by a question from Chunky, “Well, was your father a songster like you, papa?” Jonah had been taught by his papa to play many different instruments. He passed on this love of music to his son Chunky. And even as an older man, Jonah’s voice was always heard like an angel in church, or out singing in the field. “Papa, your grand-pap, played nothing but old hymns, da hymns, papa was regular church man.”

“When I’s young, I didn’t, just hollered reels, just fiddled and reel, you know, all the time, my singing. Everywhere you hears me you hear me singing a song, a reel. And out in the field that’s what I’d do. Hollering, singing reels.” One of the youngest listeners spoke very softly, “And what was it you sang about, Jonah, the cotton?” He replied, “About uh, little Joe. Little Joe, my Sam told me to pick a little cotton, the boy says don’t for the seeds all rotten. My Sam told me to pick a little cotton. My boy says don’t, the seeds all rotten. Get out off the way, old Dan Tucker. Come too late to get your supper. That’s all I remembers bout dat one.”

“I do remember,” he paused, “Well I’ll tell you, uh, things come to me in spells, you know. I remember things, uh, more when I’m laying down than I do when I’m standing or when I’m walking around. Well, I belonged to, uh, master, when I was a slave. My mama belonged to master, but, uh, we, uh, was all slave children.”

“Now in my boy days, why, uh, boys lived quite different from the way they live now. But boys wasn’t as mean as they are now either. Boys lived too, they had a good time. The masters da, didn’t treat them bad. And they was always satisfied. They never wore no shoes until they was twelve or thirteen year. And now people put on shoes on babies you know, when they’re two year, when they month old. I be, I don’t know how old they are. Put shoes on babies. Just as soon as you see them out in the street they got shoes on. I told a woman the other day, I said, I never had no shoes till I was thirteen years old.” She say, “Well but you bruise your feet all up, and stump your toes.” I say, “Yes, many time I’ve stump my toes, and blood run out them. That didn’t make them buy me no shoes.”

“And back then, I been worn a dress like a woman till I was, I believe ten, twelve, thirteen-year-old,” A question could be heard, coming from under a blanket, from someone with a feminine voice that was thought to be fast asleep, “So you wore a dress, Jonah? He answered, “Yes. I didn’t wear no pants, and, of curse didn’t make boys’ pants. Boys wore dresses. Now only womens wearing the dresses, and the boys wearing the pants.”

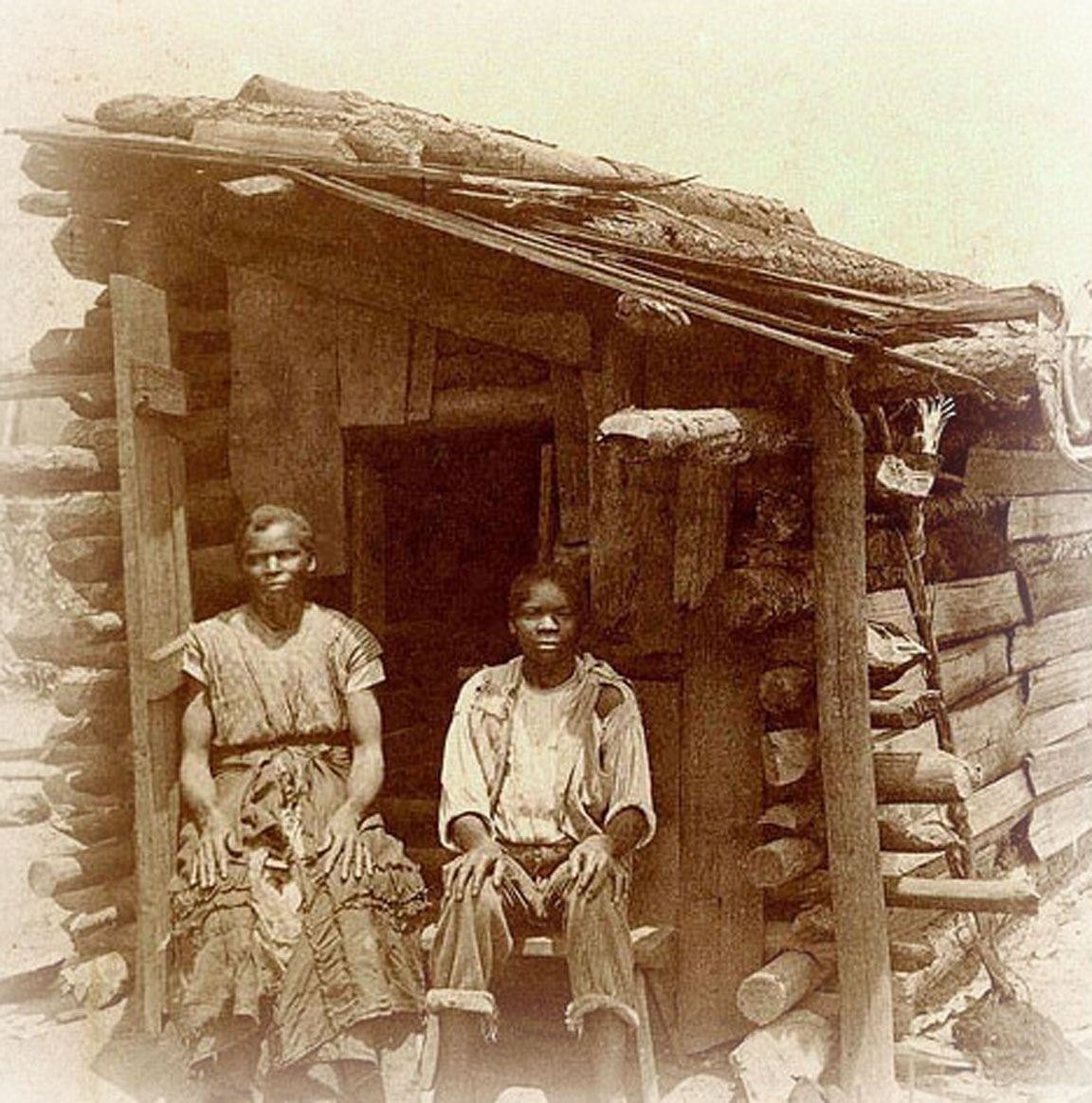

Jonah pointed to the person laying under the blanket and said to her, “Colored people didn’t have no beds when they was slaves. We always slept on the floor, pallet here, and a pallet there. Just like, uh, lot of, uh, wild people, we didn’t, we didn’t know nothing. Didn’t allow you to look at no book. And then there was some free born colored people, why they had a little education, but there was very few of them, where we was.

The more Jonah spoke to his audience, the more he thought of memories to share with them. “And they all had uh, what you call, I might call it now, uh, jail centers, was just the same as we was in jail. Now I couldn’t go from here across the street, or I couldn’t go through nobody’s house without I have a note, or something from my master. And if I had that pass, that was what we call a pass, if I had that pass, I could go wherever he sent me. And I’d have to be back, you know, when uh. Whoever he sent me to, they, they’d give me another pass and I’d bring that back so as to show how long I’d been gone. We couldn’t go out and stay a hour or two hours, must be something like they send you.”

“But I couldn’t just walk away like the people does now, you know. It was what they call, we were slaves. We belonged to people. They’d sell us like they sell horses and cows and hogs and all like that. Have a auction bench, and they’d put you on, up on the bench and bid on you just same as you bidding on cattle you know.” “Selling women, selling men. All that. Then if they had any bad ones, they’d sell them to the Black Traders, what they called, the Black Traders. And they’d ship them down south, and sell them down south. But, uh, otherwise if you was a good, good person they wouldn’t sell you. But if you was bad and mean, they want to beat you and knock you around, they’d sell you what to the, what was call the Black Trader. They’d have a regular, have a sale every month, you know, at the courthouse. And then they’d sell you, and get two hundred dollar, hundred dollar, five hundred dollar.”

“Oh, they had a terrible time. Husbands, wives, families, all violently separated, torn apart. Sold to different place, probably never to meet again. Colored people that’s free ought to be awful thankful. When I was in slavery you can’t never do what you want. Now that I’s freed man I can tell me what to do, nobody else. Now in these times you-all here can do what’s ever you want. You can choose which way you go down dat road.” Jonah smiled at them with that toothless grin again.

The children witness his big smile melt into a very long sad face. He took a deep breath and began again, If I thought, had any idea, that I’d ever be a slave again, I’d take a gun and just end it all right away. Because you’re nothing but a dog. You’re not a thing but a dog. Night never comed out, you had nothing to do. Time to cut tobacca, if they want you to cut all night long out in the field, you cut. And if they want you to hang all night long, you hang, hang tobacca. It didn’t matter about your tired, being tired. You’re afraid to say you’re tired. They just say, well work.”

Jonah drifted off into a privet memory and by the dim light of the fading fire you could see his eyes water. After a long pause Jonah took a deep breath and gave out a long sigh. He used his pipe once again as a pointer and motioned up to the heavens. “When papa died it left us small children just to live on whatever people choose to, uh, give us. I was, I was bound out for a dollar a month. And my mama used to collect the money. Children wasn’t, couldn’t spend money when I come along. In, in, in fact when I come along, young men, young men couldn’t spend no money until they was twenty-one year old. And then you was twenty-one, why then you could spend your money. But if you wasn’t twenty-one, you couldn’t spend no money.”

“And my mama, she bound us out for a dollar a month, and we stay there maybe a couple of year. And, she’d come over and collect the money every month. And a dollar was worth more then, than ten dollars is now. And I, and the men used to work for one dollar a month, twelve dollars a year. Used to hire that a way. And, uh, now you can’t get a man for, fifty dollars a month. You paying a man now fifty dollars a month, he don’t want to work for it.” There was a long pause. Finally, someone broke the silence, “You’re not getting tired are you Jonah?” When he did not answer right away all who were still awake assumed the answer was yes.

But after taking a long breath and looking around at who was still up Jonah began again. “I was thinking about oh, now you know how we served the Lord when I come along, a boy? We would go to somebody’s house. And uh, well we didn’t have no houses like they got now, you know. We had these what they call log cabin. And they have one, old colored man maybe one would be there, maybe he’d be as old as I am. And he’d be the preacher. Not as old as I am now, but, he’d be the preacher, and then we all sit down and listen at him talk about the Lord. Well, he’d say, well I wonder, uh, sometimes you say I wonder if we’ll ever be free. Well, some of them would say, well, we going to go ask the Lord to free us.”

Jonah folded his hands together, closed his eyes, and began to pray, “Our father who art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done. Give us this day our daily bread. Just like in that day. Deliver us not only from temptation but deliver us from sinning or and forever dying. Oh, calling on our God this night.” Jonah opened his eyes and raised his hands to the sky, “Whereas old time days. Calling down on all of you this night. Calling on you holy, holy, days. Oh a, Lord have mercy. Your mercy keeps us going. Sometime up. Sometime we are down Lord. Oh, Lord. Prophet give me. We are poor, tore down. Oh Lord King, help us round and round about way this evening for Jesus. Oh, Lord, have mercy. Your mercy give us strength. Oh, calling on our Lord God this night. Oh, Lord up there in heaven. Oh, Lord. Take us there oh Lord. We don’t want to ware these chains. Oh, what you need, put it in the trust of the same God of Israel.”

Jonah braced himself with his hands on his knees and stood up slowly. He looked around for some more wood to put on the fire. Large sparks hurled themselves skyward when he tossed on more fuel and brought the fire back to life. The light from the flames lit up the faces of the listeners and to his surprise all eyes were open. Almost at once two children asked the same curious question. “Just how old are you, Jonah?”

He had a great big toothless smile when he answered them, “I really don’t know. I born in slavery. Now I can’t tell you my own age. Hmm? You know why I say, I don’t really like to talk about it. I don’t know my own age, but I was born in slavery. I didn’t born free. I born in the old slavery. That’s the time I come up.”

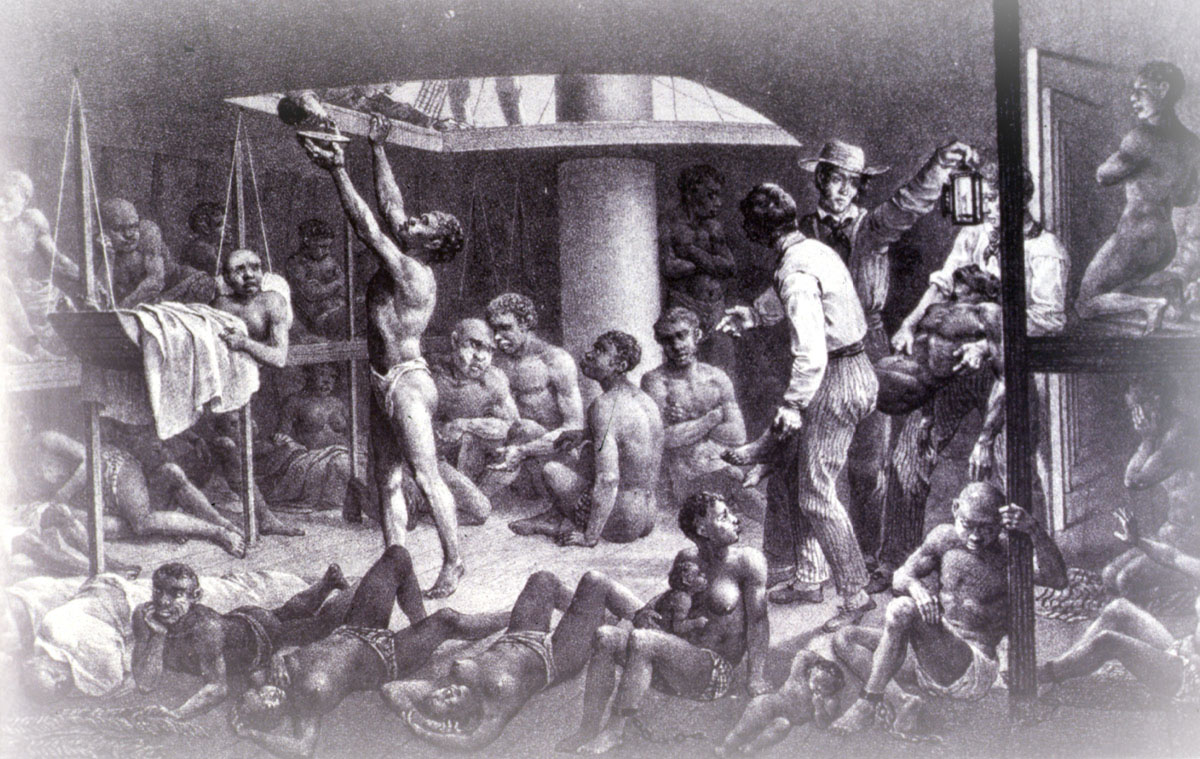

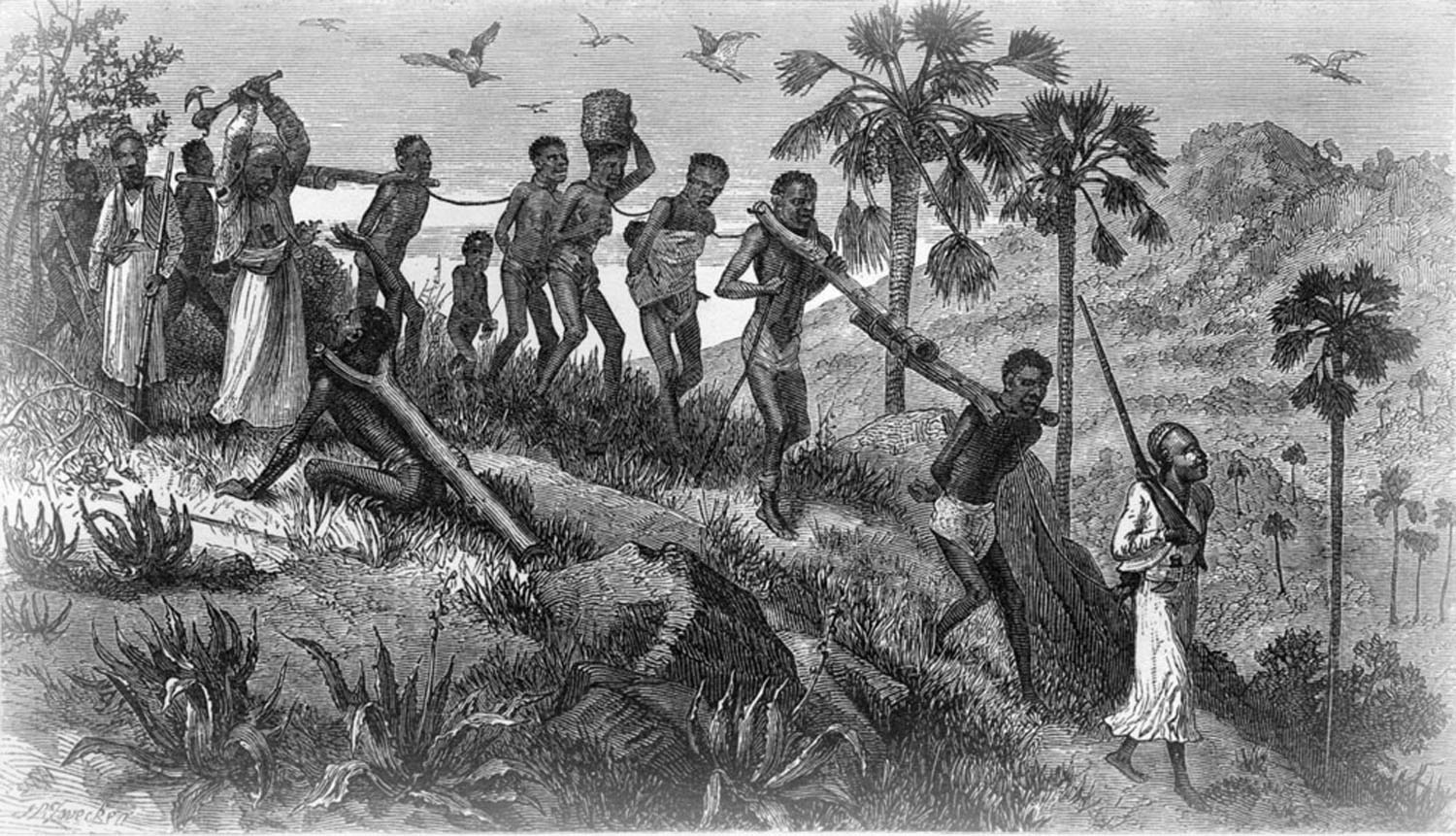

Jonah relit his pipe. He took a big puff and blew out a perfect white smoke ring. Then poked his finger right thru the center of it as he begun to finish his storytelling. “I was born in that, uh, born in Africa. And come to the United States. You see that was in slavery time. They sold the colored people. They sold the colored people. And they bringing them from the Africa. And they brought me from Africa. I was a boy child.”

All the captive colored people on a slave ship had a very bad time. Jonah experienced this, not only as a slave, but also as a small motherless child chained to adults that were fighting for food and water. They kept the men and woman separated on the slave ship. Jonah had to fight for survival as small child chained to men that wanted to kill him for his rations. He spoke with a real fear in his voice, “The colored folks want to throw me off the boat coming from Africa. Them other coloreds say, “Throw him overboard!” I was in cuffs. Just a sprout boy child chained in cuffs. They all shout, that the Black traders, “throw him overboard, let the damn whale swallow him like he done Jonah.”

“Hadn’t have been, the colored one want to throw me off, hadn’t have been for the Captain of the boat. Captain of the boat was a white man, but the colored is the one wants to throw me off the boat. The colored, the colored people always did hate me from a child. Bringing me from Africa, the colored want to throw me off the boat. They say, “Throw him overboard, cuss. Throw him overboard. Let the, cuss, let the cuss just go feed the whale.”

Another puff, another smoke ring, and he continued, “They bring us from Africa, Liberia Africa, where I was brought from. And put in the United States. Me know, the southern people bought colored folks, put you up on a block and sell you, bid you off. The highest bidder gets you. Highest bidder gets you. And they got to mistreating them so.”

Another puff, another smoke ring, and he continued, “They bring us from Africa, Liberia Africa, where I was brought from. And put in the United States. Me know, the southern people bought colored folks, put you up on a block and sell you, bid you off. The highest bidder gets you. Highest bidder gets you. And they got to mistreating them so.”

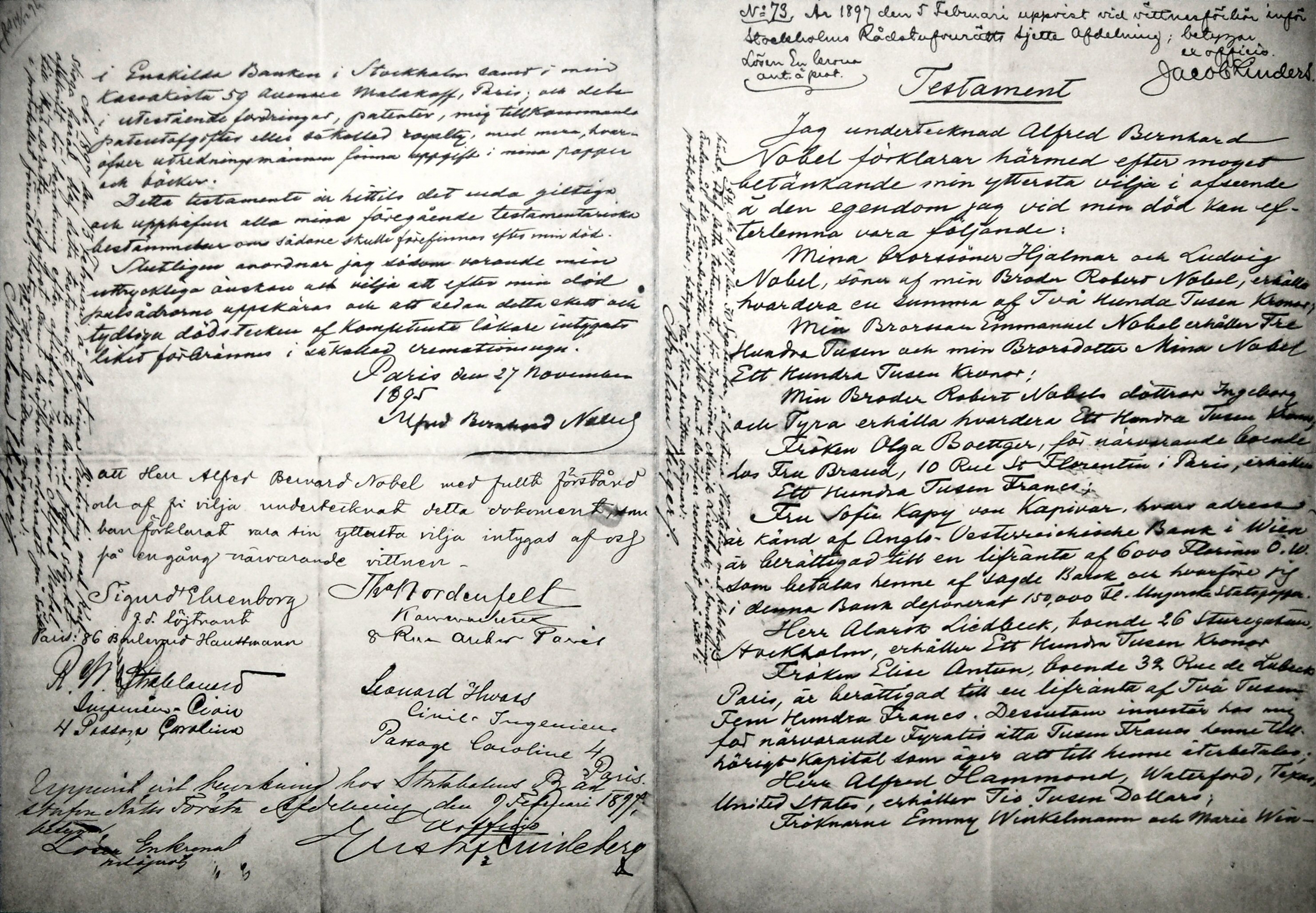

“Oh. I was in, in uh, when they went to New Orleans, that’s where they sold the people. The man that raised me, he buy me. The man raised me buy me. They would try to put you up on the block to sell you. He was master Jake. The man was master Jake. He name me Jonah that’s the name I go in now. Jonah. He name me. Jonah cuse them coloreds want to toss me to that whale. I got my last name some time ago, later.”

Part 2 Jonah saves the farm:

Jonah began the story of how he got his last name. He projected a feeling of great pride when he spoke about his heritage, his history. He knew darn well that he alone might be the last oral historian in his family’s long line of story tellers, that brought the past to the present. Not all Jonah’s memories were bad ones. He was eager to share the next chapter in his life with his young listeners.

“Some time later, there was a great and powerful storm, all the winds came from the east. Blowed feathers off da chickens. Bent the trees over, then all get very scary and still silent. No wind no how. Hounds all a houlin, barking caring on an such.” He paused long enough to hit the pipe and take a big spit right into the fire. “Animals all runned off. Overseer Black Adam he have a fit cuse he in a fix. He man-in-charge while the master off. He get punished, bad punished if things not right when master home. The thought of punishment was too great on Black Adam. So he runned off with the last horses. Now I Jonah, knowed that things getten badder. Then wind came up from the west stronger than other. It broke trees off in other direction leaving just stumps. Nothing but fire wood used for. All firewood, all firewood and broke stumps.”

“How I now living now, I no, know. I was praying, Jesus up dar in heaven, gets us out this wind. I believes, I believes He hep me be safe, and gets us out this wind. Wind so high ain’t see no nothing. But I started singing. Singing like I’s in the field. Singing like calling for someone. And all the people, colored people, white people came running at me. There was so many people I scared. I ran to the shed with all the cotton. Just jumped in all that cotton. People and cotton. Wind and cotton, in you mouth, in eye. Some sang da Lord’s Prayer, some cry a lot and holler. All safe, only-est one person got front teeth knock off, hit by windy board. No kill. Thank Jesus in heaven. No kill. No kill.”

“When master come home he seed the mess from long way. It days for he home. The master was so pleased when he found out all that had been saved, from all that was lost. All the peoples, colored folks, the white folks told him about Jonah singing. How they had trusted me to go to the safe place of the shed, because Jonah was trusting the Lord to save him. All them had heard me a praying to the Lord Almighty and me singing. Jesus had saved us all.”

“The master broke right down and teared his face. He freed me and my missy wife. He gave to me a team and wagon, so supplies, tools and money to go north and buy a farm that belong, me owner. The master told us that a great war was coming and we and my kind needed to be on the other side of the mountains where they be safer. Safer north. Safer North. When master freed me he name me whole. He say, God saved you, God freed you, so now you name is Jonah Godfreed. He said millionaires die and leave all they got. Everything they got, they ain’t carry nothing with them but thar name. So, he named me Jonah Godfreed, so to, a good name to take with me.”

“When he, uh, when he bought me at New Orleans, he raised me, in Texas, Galveston, Texas where I was raised in. And the man that raised me, he name Jonah Godfreed, and that’s the name he give me. He gave me Jonah Godfreed. He always teached me and his children. He treated me just like he treated his children, in everything, not one thing, everything. We ate together, we slept together. All the boys now, we just talking not about the women now. All we the boys slept together. I was, uh, raised with his own younglings.”

“My mama was a house woman, and uh, my father was a field hand, and white folks kept me around the house to tote cool water. Houseboy like. And uh, they had two weavers weaving, had two looms running every day. I’s big boy, carry cotton onto weavers to make weaving.”

“Well you know I’d go out in the quarter to play with them, other children. And if I hurt one and they caught me, they would wear me out. Well the, the white folk told me, when they get at me, make it to the yard. Well sometime I’d go out there and get to playing, one would hit me, I’d get a brick and show it to him and to the yard of younglings. Don’t nobody say nothing after that. And, uh, I, went on that-a-way.” Jonah turned the right side of his face to the fire so all could take a good look. “Yes, sir. And that scar,” pointing to his forehead, “because a boy throwed a rock and hit me here. When, when, when ah, I was ah, young, you know, and hit me. When I was little. Coming on out there, I call it, Old Lady Slop Room, after done eating.”

“And then, as I went on to tell you about, they made molasses way back then. They made wood, the carpenters made wooden mills. And they’d grind that molasses and they had a vat, big kettle to make it in, you know, had big fire put the kettles on. And when that molasses was made, they had a big long trough to pour that molasses in. No barrels at all. I never seed a barrel then, nothing but long troughs. And when you get your molasses made, they had plank to cover them troughs.”

“Now, now when I was a boy they used to make soap. Well I was large enough to tote water to the soap makers to put on ash hopper. Now they didn’t have no barrels, they had boards, you know. And uh, them boards come in that-a-way,” Jonah pointed off the his left, ” you know,” then he pointed back to his right, “that-a-way, them boards was there. Well, all these here, and you’d lay some crossway to hold the ashes. And then I’d tote water and put on that ash, ash hopper for the soap maker. Now he’d make soap for the whole plantation, and uh, make about two or three times a season. And along then, I ain’t seen none, no bar soap. They might have had some at the big house, but I never seed none.”

“And had, uh, something dug in the ground, hole, deep hole and board up on each side, it was plank. Well it was about three-foot-deep I reckon, and about eight or ten foot long. Well, they tan leather. You smell if from far off, is bad, bad, nasty, is nigh as I can come at it, but I knowed right where it was and which way to walk. They’d lay a, lay a bark down in that hole, and then they’d lay, lay a hide over that bark. And then they would lay another layer of bark and another layer of hide, till they got it like they want. And then they’d fill that thing up with water. But now, before they’d tan that, that leather, they had to let it lay a while and get the hair off it. And when they got done with that leather it’s just like any tan leather, and they had a man there to make shoes for all us. Now we was children, good size children, going about, that shoemaker make shoes for we children. And the old folks too. Was my first shoes, Jonah shoes.”

The next request came from one of the older boys. When he asked his question, it sounded like the young lad had a big chip on his shoulder. “They treat you pretty good?” “We had mighty good white folks, my memory, far as I can remember, you know, mighty good, mighty good.” Jonah answered him with confidence that he was telling the truth. “You know they must have been good. Yes sir, they treat me nice. They treat me nice as they could treat me. I’s came up here, over here, from Texas to Pennsylvania, United States. An’ they all treating me mighty nice, all the white folks that know me, they treats me nice. And if I want anything, I’ll ask for it. I was taught in that-a-way by my old master. Don’t steal, don’t lie, and if you want anything, ask for it. Be honest in what you get. That was what I was raised up with. And I’m that-a-way today.”

“I know of times they, when, when they mistreated people, they did, and I hear our folks talk you know, about them whipping you know, till they had to grease their back to take the holes from the, the back. Good Lord have mercy. That was bad sure. Them white folks were that a way. But master sure didn’t allow his colored people be whupped, no how. They use the whip on, horses and the ox, not ever hurt his coloreds. Not ever hurt colored folk.

All the younger Godfreeds wanted to know about their grandma. Chunky was the only one that had the courage to ask his papa, “you haven’t told us anything about your missy wife?’ It got real still then. Everyone that had been up listing to Jonah all night had notice he avoided talking about her. The silence was deafening. Then he spoke very sharply, “she dead too soon.” As his own words sunk into his memory, the older man became young again, as he thought about her.

“She good as any man, can plow and lay off a corn row as good as any man. Chop, and chop, pick cotton. She pick five hundred pounds of cotton. Knock out five hundred pounds. Then walk across the field and, and hunt watermelon, pomegranates and such. My missy, your grandma, was in the big house. She house slave.

Take care of the children. In the morning before sun, getup, put on the cereal, and stop and wash the children hands, brush their hair. She would put the table cloth upon the table. And get the mat and put them on top the tablecloth. Then get this knife and fork and plate, put them upon the table. So, when missus and master and company sat down eat. Then she and the old woman feed all the colored.”

Some one asked, “Out of all you told us tonight what do you remember, the most dear to you heart.” Another voice, “What is your fondest memories of the older days.

And yet another, “What else did you do when you were our age?”

Jonah was, all-ready, with his answer before they had finished asking their questions. But his response was just not what they had expected when they asked him. He had lived, and survived, and grew up living as a slave. He surly had seen more than what he had already shared with them. Their curiosity had the best of them now.

Jonah interrupted the line of questing and said this, “The thing I’s member the most from all that bad happen, the thing most dear to my memories in my heart, most important thing I learned, I teached to you now. The Lord Jesus loves ya, he was always there for me, Him there today, right now, and He there for all of you to. The most valuable possession I’s still have with me today from my boy times, is my talk with Jesus.”

Jonah took a toke on his pipe, and another, and another, and finally got it going again. But the weed had all but run out, and there was nothing left but hot ash glowing in his pipe. In one motion, with little effort, he was reloaded, puffing and spitting out tobacco, and his story.

“I was born in Africa. I’s born a slave to my mama, she was slave to Black men that sold colored men, woman, children, to white sea captains on big ships. They bring us to New Orleans, United States to be sold. Black men started me a slave. Black men stole colored people from their home.

Black men put me in chains, and get to the white sea captains. There was some white folks that in slavery that teached us about Jesus. We did not understand, just want to be free from slave. So, we believe the stories. I’s pray just like they did. And I’s know Jesus going to hep me not be slave. I’s always talk’in to Jesus.”

“I’m telling you now we ain’t nothing without the Lord. Got to put our trust in Him that gave us. That’s the onlyest way I’m still walking round today. I trust the Lord will bless you all. You all hold onto the best you can while we live. Take the Lord with you.” Jonah begin to clap his hands and sing. “Ever hold you hands in his?” Then he hummed a few lines. “ I would say, get in trouble, all you got to do is call Him. See! Only one you can call.”

“Yes, sir. Call Him. Call Him. That’s all of you. And this young lady right here, you know,” Jonah leaned over and hugged the child under a blanket that had been leaning on him for a while to keep warm. “I know ah, you all’s buddy, that’s why I come up here tonight talking to ya. Talkin about slavery time and all. Great God almighty there’s our Lordy up heave there. Him name Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. He fix’in a great place, gold roads, nobody hungry, no body hungry. Colored folks, white folks, all be gathered as brothers and sisters, brothers and sisters in Christ. Swing low sweet chariot take me home to Jesus.”

“And I’m telling you now, our people got to do right in the sight of God, because he knows all about us. And I’m, and I’m so thankful. And I tell you, young people these days, the young folk, the young folks ain’t taking the time. Is ya? Time to read the Bible, those that read, those that read can teached those that ain’t read no how. For God himself up dar in heaven, he sent his onlyest boy child to be a slave down here on earth. He dead on a cross of wood, piece of a tree, then used them big-o-nails put thru hands and feet on him. He died to set all the slaves to sin be free men and woman. Now, all we-all do here and now, is believe, believe, just in what he say down in his Bible book. Youngings dat taking the time, read that book, knows what God want. All peoples book. All peoples book. For them.”

Jonah’s ability to remember the past was picking up speed. He found himself like a preacher man on Sunday morning. He look out at his gathered congregation and said, “I was at ah, a white man church, and ah, a man got up to speak. You know, we never heared the sermon preached before, bout dry bones. The man couldn’t even speak, until they wanted him to. So, when he got put up on a bench, up front, he come there to speak, I take notice. I take notice, in that big Bible book in his hand. Preacher man say he talk bout dry bones in that Bible. And we ain’t know nothing bout no dry bones. Preacher man says God gave us, the Lord’s 10 commands. Lord is coming. Yes, sir, that day is coming. That day is coming. That day is coming and we got to prepare that day.”

“Now all us knowed God gave us, the Lord’s 10 commands. Yes sir, we all knowed Lord is coming, we just want to know bout dry bones in the Bible. Preacher man went on to tell us, “That day is coming. That day is coming and we got to prepare that day. I want to hear the first trumpet when it blows that morning. God, gave us commandments, Lord. God gave us Christ and he taking us all home to heaven.” Then preacher man say he talk about God raising the dead, and how the Lordy his self, have to come and pick up all our dry bones. He raise to heaven all the dead folks. We all just bust’in at the seams of our britches, laughing at that preacher man’s talk bout dry bones.”

“Well, I tell you don’t people, don’t, don’t pray like they used to. They don’t care so much for it. Who is we all without the Lord? Hmm? He hold us in the hollow of his hand. All power in his hand. But the young ones is forgotten that. Yeah. But I’m telling you myself. And then they shame, they don’t, don’t honor him like they ought to. I pray up to heaven, please don’t lock the door. Jonah is coming, Jonah is coming. The witness is in our breath. The witness is in our breath.” Jonah picked up a bug with a small stick and he surprised everyone when he put it into the fire. “Judgment is near at hand. It’s near at hand. It’s written in the Bible. Time ain’t long. Do you believe it? I said, Luther, you can go right ahead, be dat Satan. But it’s the truth, but God are going a put a curse on you. And I say, you mark what I tell you Devil man.”

Someone asked, “tell us about when you were a little baby and a little boy.” Jonah just laughed, “Oh, when I’s was a baby I, well I, I’s couldn’t remember nothing. I couldn’t remember nothing from when I was a baby. No sir.” That remark got a big chuckle from the peanut gallery. Jonah took a toke on the pipe and the smoke came out his nose as he started talking again.

“Back when we was children, you know. Wasn’t able to, to, tend to no, tend to no other children. I had a older brother though, he could tend to children. In the, you know, just sit them down in a corner and put this child, you know how little children, put this child in between his leg, and then hug his hand around this child, that’s the way he nursed them. Couldn’t stand up with him. Couldn’t, you know, just enough, you know, shake him this way in the arms.” Jonah pretended to be cradling a baby in his arms. “I, I can remember that. I had a brother, name, Willard. And he just shake that child so gentle like in his arms. Set him in the floor sleeping. And he, and if that child kick much, he’d fall down and play dead, kick him over too, you know, and catch him in his arms and hug him big time. Willard he got tick fever, mostly die, he can’t do to much no how sept baby keeping”

“And they had certain times to come to them childrens. I think about this like a cow out there will go to the calf, you know. And you know, they’d have a certain time, you know, cow come to his calf and at, at, at night. Well, they come at ten o’clock. Everyday at ten o’clock to all them babies. Give them what nurse, you know. Them what didn’t nurse they didn’t come to them at all, the old lady fed them. Them wasn’t big, wasn’t big enough to eat, you know. She’d ah, the old mother had time, you know, to come feed um. When that horn blowed, they’d blow the horn, for the mothers, you know. They’d just come just like cows, just a running, you know, coming to the children. Out of the fields. Out of the fields. I don’t know how old they, couple years, till it was big enough to walk, I guess”

One of the girls asked, “what bout when the babys get hungry at the night time, did they feed them?” Jonah answered, “yes, ma’am, twice a day. Come there and nurse that baby. He couldn’t eat, you know. But one dat could eat, he wouldn’t come until dinner time. But little one what couldn’t eat they’d fed them in the shade.”

Chunky had a great interest in his father’s past. He had already retold some of the stories to the younger ones in his family. His favorite ones were about, his papa, when he was his age. So he asked Jonah, “Did you mama pass down any stories about you, when you was our age?”

“I remember when she used to tell me about the day when I’s was uh, little sprout and used to ride the oxen and things. Yeah. Oh, my papa drove some, the big old oxen. He had one with, uh, big with wide horns. Oh, looked like a house.” Jonah seemed to slip into a second child hood as he described his childhood experience. He even got down on his knees to make himself shorter, as he encouraged his listeners to believe he also once was young.

“Wide horns, and, and, and I used to set up there in between them horns. And he, his name were, Old ’Steam Boat. His name Old’ Steam Boat. He named Old’ Steam Boat, cuse when it be frost cold, the steam shoot out his nose like the old river boats smoke. The other ox him name Samuel.”

“And papa drive them to church that day. And put da children in the, in the old, old ox wagon and carry them there. And, and I’d get up there and on, and on, and on Steam Boat, clinging on Steam Boat horns, and sit up there. Sit up there just as big as I was setting in a house. Him back so wide, so big, I could lay down all flat and nap a while.”

“Well, papa went to, went to, to lumber. Want to get some lumber, and he had to go cross the river. It was in the summertime, about the same this year, in June, and the, the, the old oxen got hot. They got hot. Oh, and then, uh, when we no knowed anything, papa knowed anything, them old oxen done run off in, runned off in the river with us, with us, with that, with that wagon.”

“And, and there I sat up there in the old’ Steam Boat horns. Sit up in old oxen horns. Oh, and he’s wading through the water, and I was setting up in there. I stayed in there too. I held to his horns. I held to his horns. I didn’t fall off in the river. I held, I’m telling you, I held it too, yes I did. Oh, oh, my papa was just a whipping with that whip, trying to get them out of that uh, river. And we was, and old Steam Boat and Samuel was coming through. They come out too. Yes they did but not till they got good cooled, and a big drink. They no move till done gettin big drink.”

Someone asked, “Jonah, what was the worst thing you can remember about those days”

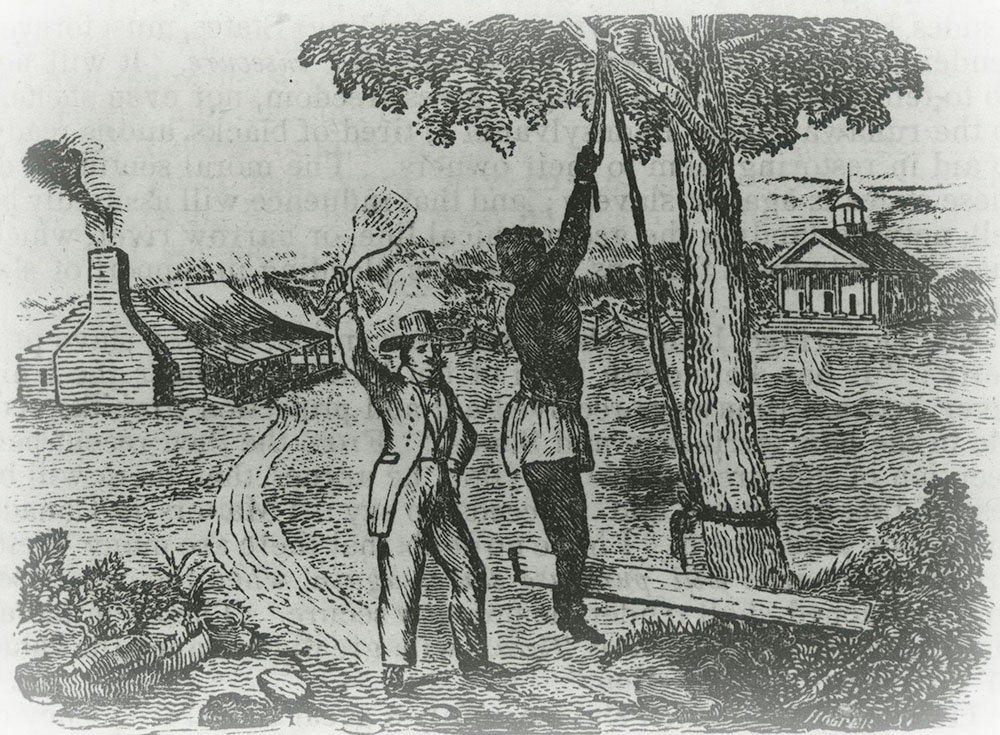

Some things a person experiences in their own life are too bad to remember. From some experiences, we learn a greater lesson from going thru it and it should never be forgotten. Jonah tried to walk the very thin line between the two, when he spoke about the past, to his youth of the feature. “Some white folks hurt bad the colored folks. I’s don’t, don’t much like talk bout dat, couse have to think bout dat slavery time, slavery time bad for colored. My eyes see bad, bad thing one day. Remembers a hanging. But ah, ain’t nobody know what the man done or nothing. Ain’t nothing at all about it. And they hung him. They tied and hung him. I went to that place, they were hanging a boy, standing there looking about was, his mama, brothers and all, out yonder held back by the overseers.”

“Yes, ma’am, I stood and looked. And the, the a gallows was up as high as here covered this house, and got all the people all out the field coming around all standing in line. And this, this, this boy standing there rope around his neck. And ah, I tell you that’s something for you to look at. I don’t know what I ain’t seen in my life. Terrible sight I know. And when they got ready to touch the lever, and when they touch the lever, that boy, that he had the rope around his neck, and they just cought him hanging by his neck. I’m afraid that believe your eyes. Believe your eyes.

There was a sudden burst of questions all at once but the voice that was the loudest got an answer, “You say his mother was there?”

“Mama, father, brother and all right there in the line. Overseers make them in the line, so they can watch good. And I never saw such crying in all the days of the Lord. And I’m telling you, start living on the Lord. And, I’m just telling you all. They say he moves in mysterious ways and his wonders are many. And he plants his footstep in the sea. And he rises up on the storm. And when this storm come, there was, this boy they hung, and they say there was a hundred men, right around here just to see. And they, they, they would not bury the boy. They burn him up. They burn him up. And they had to burn the boy up by tonight you see, you see, you see. And all the people stood and watched till dark.”

Everyone, kind of knew, that after so much time one of the girls would ask another question about their grandmother. No one ever heard of any other name for her other that what Jonah always said, my missy. That question, strangely, was avoided by all, and was not being asked by the young listeners. None of them asked because, that’s the way they all remembered her, my missy. She had died long before any of the children were born.

Once again Jonah’s attitude abruptly shifted, back, back to a very deep sore spot in his memory. This was why he did not like to talk about his life as a slave. Sure, everything was bad while he was a slave. But the hardest thing for him to think about it all, was the memories of her. These memories were so special and precious to him, but they reminded him of what he had lost. Lost long ago. That is why he never wanted to talk about slavery times, because he had to think about her. But Jonah thought it was more important that the children know about their grandmother, so he kept answering all their questions.

Jonah began, “She was born behind a rich white woman. She sure was. She wasn’t no poor woman. No, she wasn’t. Her husband was living then. Oh, she wasn’t no poor woman. She, ah, she brought my missy up here from the South, oh from one the other, in this country. She brought my missy here to Texas, when she was young. Oh, my missy was young. She wasn’t grown. Oh, she brought there to the land where I was. Oh, way up Texas, and get grown.”

“In day time, my missy, she tends to all the children with the old woman. Tend to the children. Just like, you know, you bring a whole lot of children, you know, and put them down, you know, at one house. Well, there somebody have to look over them, you know and tend to them, that way. Just a house full of them children. And if one act bad, you know, they’d whup him. They’d whup him. And if the old woman didn’t tend to the children, they’d whup, they’d whup her too. You know to make her tend to the children, she wasn’t doing nothing. Well she was a cripted woman, you know. She was an old crippled woman, and they’d whup her.”

“But there be a house, you know, where are feed all the other children. I call that a slop room place. After she done, in the morning, at the big house, my missy, goes and feed the coloreds. And they had trays, I don’t know where you see a tray today. Wooden tray. Dug out, you know, all about that, that long.” Jonah held out his arms and stretch as far as he could while still setting down. “And all of them you know would get around that tray with spoons, and just eat. I can recollect that because I ate out the tray. With spoons, you know, and eat, treat you like mush or soup or something like that. But feed them, you know, before twelve o’clock. And all them children get around there and just eat, eat, eat out that thing. No table, no cloth, ain’t no fork and knife, big long tray, and gots his wood spoon”

“And that old woman, you know, she would tend to them. Just like slopping hogs wasn’t it. It, just like a tray, you know, just like a tray, you know, you have, it’s made just like a hog pit, a hog trough, you know , hmm, that nasty. And, and ah, of course you know they’d wash them things and scald them out for the children. I didn’t see them scald, but that what they told me, they scald them out, you know. For the children. And ah, them children eat out of that, that thing and, that’s with wood spoon, if one would, if one reach his spoon over in the other’s hand, over in the other’s place, he going hit him. Hit him, you know. Knock that, knock that there, s-s spoon back, you know, on his side. On his side.”

“Oh. Well, my master, have me to help my missy with the big house work chores. Tote water, stacks the firewood box. I’s big enough to help her, she young yet. I be da yard boy. She be house slave in da, big house. I’s don’t know how we not get together when they has us in the pantry night time, so’s she can be ready to fix vittles in the morning. Stayed there till, was grown young man too. Kept the house, the yard and all the horses. Yah, sir.”

“Oh, oh. In them days, them days the white people had control over the, colored marriage, slavery time, that slavery time. Those wouldn’t hardly agree no mater no how. They brought my missy to this country, she wouldn’t let nobody take, take her away. She raised here there, with, with her children. She raised her there with her boys and girl. She didn’t have but one girl. Oh, but she had five or six boys, some die. She didn’t have but one girl, and she, and she was a little. She was little. She wasn’t no big girl. Oh. Oh, but she stayed there till she got to be older, then she sold.

Surprisingly it was not one of the girls that asked the next question, “Now, who did the cooking for the plantation?” From the young man’s size you tell this boy liked to eat.

Jonah turned up his nose a little. He remembered what he mostly had to eat back then, mush, fried grease and dough, and once the while, the salt pork and beans. “I don’t know what the old woman’s name done the, the cooking. A master Jake did tell me not, not long ago, who done the main cooking. You know they didn’t cook, cook in the ah, kitchen like here, they’d have a, off, off kitchen. Off from the house.” Jonah explained, “In the south it was too hot to cook inside the house like folks does now. So, they had cook fires off the kitchen yah know.”

“They cooked, you know, on the outside. Right in the yard, but no, they cooked it out, out there, and then brought it to the house. They always brought it to their kitchen, when I was a child. And then pack the vittles, you know, to the kitchen. Pack it to the kitchen. They didn’t have, they wasn’t cooking in the, in the kitchen dining room. Once, the twice, a year they do da pit cooking, we got real full too just like this day here.” Jonah rubbed his big belly and gave out a fake burp.

Leave it to one of the boys to ask, “Jonah, did you hear anything about the Indians in the days when you were young and the things that they did.” Jonah put on his best tuff man face and said, “The Indians were pretty well gone at that time down there I think. But not, farther north. Oh. I have seen them, but I didn’t know them. I’v e seen them, but I didn’t know nothing about them. But I did have doing with them a once. Met one with an ax. Caught them in the smoke house at the bacon, taking at night time. They were more hungry than us coloreds, let him take some meat but I’s took back the ax. Good for me he wanted food more than kill me. Then they all gone.”

Jonah checked his pipe, knocked out the ash on his pant trousers, and rubbed it in to the cloth. He took out some more tobacco and reloaded his friend and with the stem of the pipe he pointed to the nearest child and said, “Another very interesting thing in my early childhood was the colored baptizing. How they did it. All the candidates for baptism was standing on the bank of the pond over in the cow pasture. They all dressed in long white gowns, with white caps on their heads, ready to be buried in baptism. And the song, as they were being led into the water by the minister was this:

Oh, brother, keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Just like the light of God.”

Jonah begin claping his hands on the back beat and stomping his feet on the down. He did some real ham-boneing, between slapping his thigh, and clapping his hands.

“Oh, sister, keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning. “ Jonah grabbed a young girl about 8 or 9 years old by her hand and they begin to dance around the fire. He kept on singing.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Just like the light of God.

By this time all the children were singing to Jonah’s call and response. He sang the first line and then they all sang together. Everybody was very happy and filled with a good spirit.

Oh, mourners, keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Just like the light of God.

Oh, sinners, keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Keep your lamp a trimmed and a burning.

Just like the light of God.

The choir gave themselves a well-deserved applause and they sang some more old tunes together, they all knew from school. Jonah ask two of the bigger boys to go over to the wood shed and get a few sticks for the fire. And he sent some of the girls to fetch some water from the well because his mouth was too dry from talking so much. Jonah said, “ Maybe time for us-all-here to get down to doing some sleeping, hay?” The response is what you might expect from young children that are getting to stay up late. The response was, “NO”

A young man stood up and stirred the fire sending more sparks up into the night sky. Jonah pointed to some sticks on the ground and the boy added them on top of the red-hot coals. The dry wood quickly took off burning, snapping, and popping. It lit up the darkness with an orange glow that sent spooky shadows dancing threw out the trees. Then he asked, “Jonah did you ever see anybody get punished, ah, did they ever whip you?”

Jonah answered right away without hesitation, “Master used the whip for the farm animals. Never hurts any of us coloreds, but did hear of some. Well, once when I’s bonded out to nother plant there was a, ah, house gal that got bad treated.”

“She be a house gal running and playing with another girl, and just catched her by her wrist this-a-way.” Jonah grabbed his arm with his other hand and gave it a little twist. “Both them pushed down in a rocking chair. When their mistress come home, that girl she crying, mistress asked her what was the matter, you know. She told, that gal hurt her, hurt her wrist. And ah, and mistress asked that gal, ah, what ya-all doing in this house here hurting this girl?”

Jonah shook his head in disgust with what he was about to tell these children. He was not too sure if telling them would be a good idea. Some things maybe better left un-spoken about. But, deep down in his heart he remembered his master telling him to always do your best at whatever you are doing. “Be good boy, be good man, be honest and always tell the truth.” That what master Jake always told Jonah. And he thought to himself, “These children need to know the truth.”

This story was going to need a fresh pipe so he got ready. But when he dropped it on the ground in front of him, there was a scramble of children trying to retrieve it for him. The fastest one, won, and handed it to Jonah. He changed the subject right then and there and told all the children, “Listen to me, don’t ya all ever start, don’t ever start. Leave the pipe alone, Jonah wish he be never even try. Don’t ever even try. Jonah gots the bad cough from the tabacca. Don’t even try.” Trying to change the subject again he said, “Now where was we?”

Jonah was just stalling. He did not want to tell them this, but he did anyway. “That gal not hurt that girl, she told da mistress that. She say she wasn’t hurting the girl, but the thing is anyway, well the mistress dragged her to the peach orchard and, whupped her. I’s there, seen it happen. And, you know, just tied her hands this way, you know, around the peach orchard tree.” Jonah held out his arms in a big circle. The children could easily tell, that this story was not easy, for him to tell them. It was like he, Jonah, felt a little responsible himself for not helping her that day. “I remember that just as well, look around a tree, see, and whupped her. Well she couldn’t do nothing, but kick her feet out at them. The more she kick, more the keep whupped her. They didn’t have her plum naked, but they had her clothes down to her waist. And every now and they they’d, whup her.”

“You know, and then, snuff the pipe out on her, you know. Snuff the pipe out on her. You know, with embers in the pipe. I don’t believe what ever I seed, the pipe still smoking and snuff out on her there like that. You know, with embers in the pipe. Good God! I said, I don’t believe what is seed, I not stay to witness no more and runned off. I was wake till morning that night.”

Someone else asked, “Didn’t she scream”

Jonah choked as he tried to answer that question. He still felt like he should have done something to help that gal, but the truth was, if he had tried to help her, he would have been punished far worse for just trying. “Yeah! I think she was. I think she did, but she mouth bound too. But you see there was we, was daring to go out there, where it was, you know. Because ah, the overseer he would whup us if he catch can. You see, that overseer, her papa, her papa was the overseer but he had to whup her. He whupped her too. He really sure did whup her. Well, he ah, he a whupped her so that at the night they had to grease her back. Grease her back. I didn’t know what kind of grease they had, but they sure greased her back, and night you know, that way. They just grease her back”

“And ah, so after him, after so long on the tree, so, whupping being so long, that way they quit. Then they give her, her dinner. Late that evening they give her dinner. Late that evening of course she been whupped so bad then, you know, she didn’t want to eat, you know. If for they whupped you half a day, you ain’t want to eat no how, you know.” Jonah felt like he was going to lose some of that fine meal they all had just enjoyed. These memories made him just plain sick. He excused himself and went behind some trees. Then, the children could hear him sobbing in the darkness. They all wanted to go to him and comfort him but before anyone could move, he came back out of the dark.

As Jonah was returning to his hot seat he looked around to see if anybody had been watching. With a face full of tears, he said, “Man tears, man tears, those,” with his finger he wiped tears from his face and held them up, “are man tears. Good for man to cry when pain so much. Jesus cried for us, cried tears, Jonah cried for that gal, her tears done all used up, all used up. Jonah cry man tears for that gal”

Jonah was not the only one with tears in his eyes. He looked around and he could tell that his young listeners were deeply affected by the truth. There is no way to soften the blow when the facts hit you in the face like an old wet dish cloth. It takes a while to get the stink off. But you always remember how it smells. They all knew that the pain they felt now about these stories was nothing in compared to what the colored folks felt when they went thru slavery. Their heritage, their history was being passed on to them now.

Jonah told them that, they held the responsibility to tell the truth. They had to pass on the good stories that made them laugh, as well as the tuff times to. But this is what he wanted them to remember the most. He said, “members that the Lord loves ya. He loved us first so we-all would know how’s, ah, to love each other.” Jonah stood up, adjusted his self so that he stood real proper. Then he looked the children right in the eye, and said, “The most important I’s can ever teach you, is about Jesus. Jesus. The Lord, Jesus. He is everything to me.”

Jonah thought for moment to himself. He could look back at his whole life in a flash and he felt so unworthy of the precious gifts that the Lord had blessed him with over his life time. He had survived an unbearable trip here from Africa fighting for his life all the way.

He had been separated from his mother and left alone. And when he prayed to the Lord He saved him by protecting him from harm with the white ship captain. He found himself on the block of slavery. And when he prayed to Lord He saved him by guiding the hand of the man that bought him, to rise Jonah as his own.

Once again Jonah looked up into the sky. The dawn was starting to cut thru the clouds and the fire was going out again. He smiled at the children that were surprisingly all still awake. He could not believe it. Then he started to sing. “Do ya member a song, a old song, it called, Go Down Moses?” They all started yawning but trying to pick up their spirit Jonah began to sing and they all followed in and joined him.

“Tell old pharaoh let my people go”, Jonah sang with a real deep voice and his choir sang back with the bright voices of their youth. “Let my people go!?” and they all kept singing.

“When Israel was in Egypt’s land

Let my people go!?

Oppressed so hard they could not stand

Let my people go!?

Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land

Tell old pharaoh let my people go”

Soon the yawning took over the singing. Slowly the younger ones went to sleep. But there was still a few that could not stop talking about what Jonah had told them that night. Jonah slipped off into the bushes to relieve himself. As he returned to the smoking fire pit, he could hear a very brisk conversation about whether or not the few remaining, could talk him into more oral history. They were hooked. And like a fish out of water, their mouths were open and begging for more. In his absent the young adults had chosen one to speak for them all. A young lady that had been quiet voicetress all evening spoke. “Well, did they have church? Did the slaves have a church?”

Right away Jonah’s spirt was lifted. He loved to witness to the young people, not only in his family, but any of them that would listen to him. He believed there was a better chance of spreading the gospel to the young, more than an older person that may have harden his heart to the word. Jonah’s voice was energized when he spoke, “And another thing that I members, on that old plantation, that we not talk bout before was church. Ya see, things real poor, but we have the best church God can give us, it outside.”

The curious one asked, “In the trees?” And Jonah answered, “Under trees. Under trees. Yes, ma’am. Under trees.” Still curious she asked, “Brush arbors?” Jonah answered her, “No mam, they didn’t have no brush arbors, they just had it under the tree. You see. Just had it under a tree. And you know, because of church got no building, you know, when they started. But I know when mama and them used to go to church it be under the trees, you know.”

Jonah pointed to the grove of trees behind them. The shadows from the fire were starting to disappear in the early morning light. “Out and under, under the trees. And, and didn’t have no church houses much then. Just like, you know, you get a big old tree, but ah, and clear all out from under it, and make a, dry spot to sit down, you know, and make benches on it, you know, or sits on that ground. That’s what they have for church, in da trees.”

Chunky asked, “Just get together and sing and pray, eh?” Jonah answered, “That’s all I heard, would hear them sing. And ya know, night come, ah, Id go and sleep pretty soon. Most time I wake, so ah, I’d sing these here songs we just did sing. We used to go to church, in them trees, and sing them same songs.”