Native Americans Tribes & Peoples – part 4

Jonah saves the farm

Jonah began the story of how he got his last name. He projected a feeling of great pride when he spoke about his heritage, his history. He knew darn well that he alone might be the last oral historian in his family’s long line of storytellers who brought the past to the present. Not all of Jonah’s memories were bad ones.

He was eager to share the next chapter in his life with his young listeners. “Sometime later, there was a great and powerful storm, all the winds came from the east. Blowed feathers off da chickens. Bent the trees over, then all get very scary and still silent. No wind no how. Hounds all a houlin, barking caring on an such.”

He paused long enough to hit the pipe and take a big spit right into the fire. “Animals all runned off. Overseer Black Adam he have a fit cuse he in a fix. He man-in-charge while the master off. He get punished, bad punished if things not right when master home. The thought of punishment was too great on Black Adam. So he runned off with the last horses. Now I Jonah, knowed that things getten badder. Then wind came up from the west stronger than other. It broke trees off in other direction leaving just stumps. Nothing but fire wood used for. All firewood, all firewood and broke stumps.”

The Underground Railroad

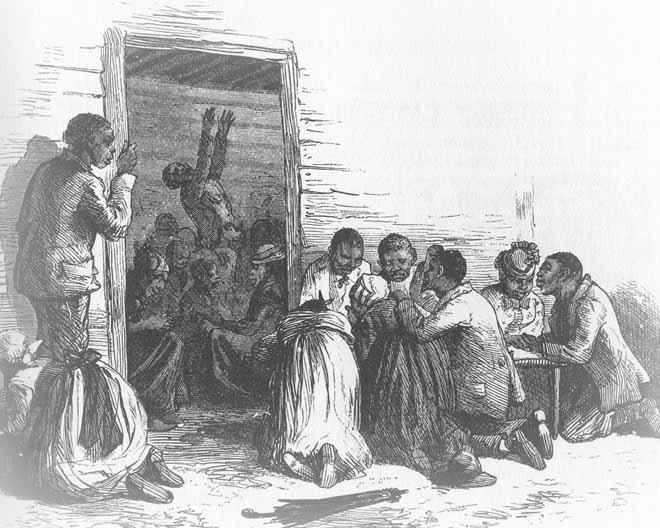

There was an expression of amazement on Jonah’s face when he said, “How I now living now, I no, know. I was praying, Jesus up dar in heaven, gets us out this wind. I believes, I believes He hep me be safe, and gets us out this wind. Wind so high ain’t see no nothing. But I started singing. Singing like I’s in the field. Singing like calling for someone. And all the people, colored people, white people came running at me. There was so many people I scared. I ran to the shed with all the cotton. Just jumped in all that cotton. People and cotton. Wind and cotton, in you mouth, in eye. Some sang da Lord’s Prayer, some cry a lot and holler. All safe, only-est one person got front teeth knock off, hit by windy board. No kill. Thank Jesus in heaven. No kill. No kill.”

Jonah cowardly bowed his shoulders and said, “When master come home he seed the mess from long way. It days for he home. The master was so pleased when he found out all that had been saved, from all that was lost. All the peoples, colored folks, the white folks told him about Jonah singing. How they had trusted me to go to the safe place of the shed, because Jonah was trusting the Lord to save him. All them had heard me a praying to the Lord Almighty and me singing. Jesus had saved us all.”

Jonah somehow found the way to speak kindly, “The master broke right down and teared his face. He freed me and my missy wife. He gave to me a team and wagon, so supplies, tools and money to go north and buy a farm that belong, me owner. The master told us that, “A great war was coming.”

Jonah said, “ He convinced us that me and my kind needed to be on the other side of the mountains where they be safer. Safer north. Safer North. When master freed me he name me whole.”

His old master told Jonah, “God saved you, God freed you, so now you name is Jonah Godfreed.” He said, “Millionaires die and leave all they got. Everything they got, they ain’t carry nothing with them but thar name.”

Holding his head high and proud, Jonah said, “So, he named me Jonah Godfreed, so to, a good name to take with me.”

Jonah needed no encouragement from the children to keep telling them more about his coming to America. “When he, uh, when he bought me at New Orleans, he raised me, in Texas, Galveston, Texas where I was raised in. And the man that raised me, he name Jonah Godfreed, and that’s the name he give me. He gave me Jonah Godfreed. He always teached me and his children. He treated me just like he treated his children, in everything, not one thing, everything. We ate together, we slept together. All the boys now, we just talking not about the women now. All we the boys slept together. I was, uh, raised with his own younglings.”

Chunky asked, “Tell us something about my great-grandma, your mother, Papa.”

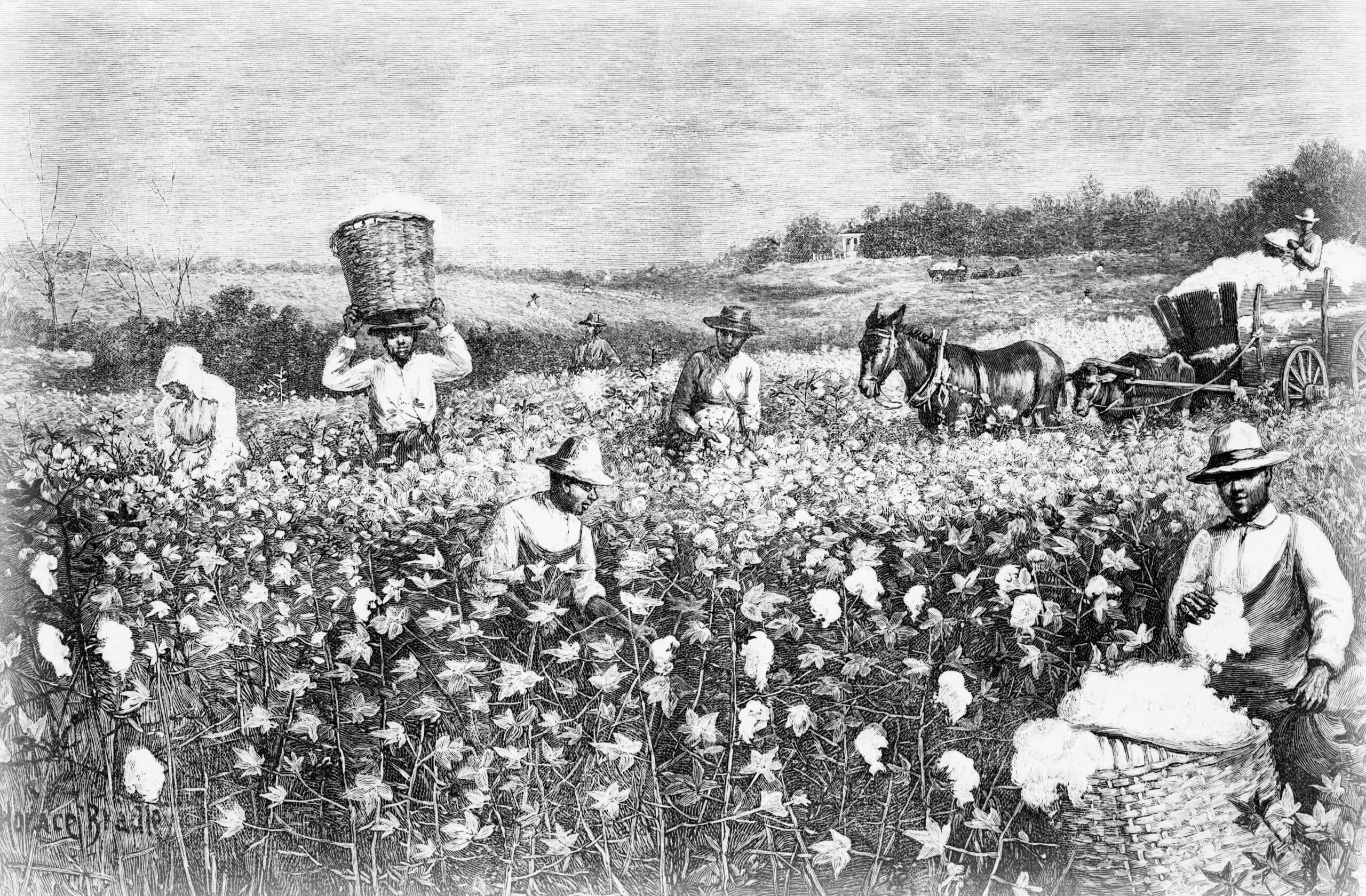

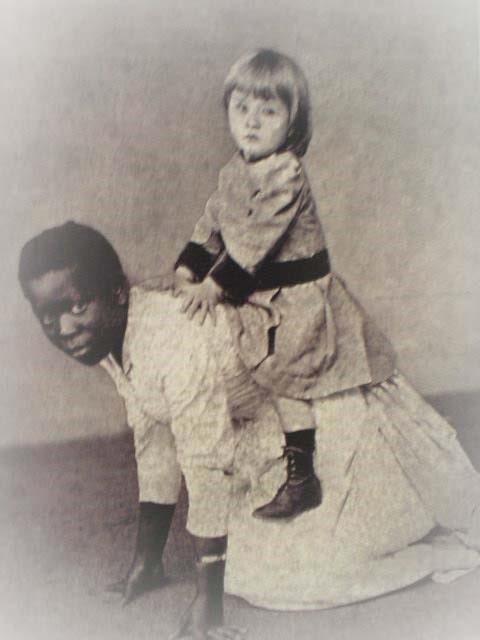

“My mama was a house woman, and uh, my father was a field hand, and white folks kept me around the house to tote cool water. Houseboy like. And uh, they had two weavers weaving, had two looms running every day. I’s big boy, carry cotton onto weavers to make weaving.”

One young lady asked, “Did all the children on the plantations play together?”

Jonah answered, “Well, you know I’d go out in the quarter to play with them, other children. And if I hurt one and they caught me, they would wear me out. Well the, the white folk told me, when they get at me, make it to the yard. Well, sometime I’d go out there and get to playing, one would hit me, I’d get a brick and show it to him and to the yard of younglings. Don’t nobody say nothing after that. And, uh, I, went on that-a-way.”

Jonah turned the right side of his face to the fire so all could take a good look. “Yes, sir. And that scar,” pointing to his forehead, “Because a boy throwed a rock and hit me here. When, when, when ah, I was ah, young, you know, and hit me. When I was little. Coming on out there, I call it, Old Lady Slop Room, after done eating.”

A boy next to the fire asked, “What kind of things did they make you do when you were a slave, Jonah?”

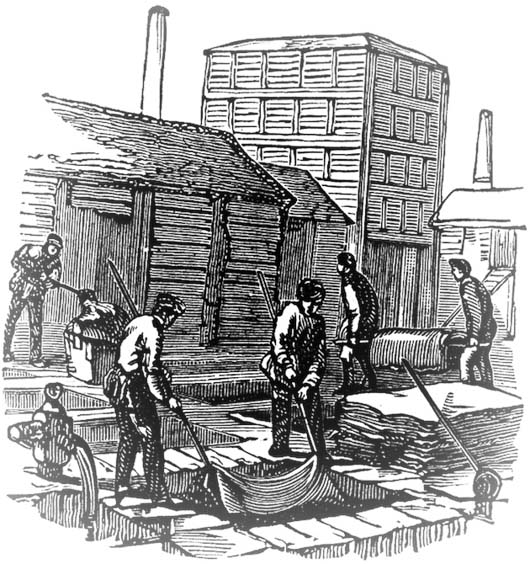

He answered right away. “And then, as I went on to tell you about, they made molasses way back then. They made wood, the carpenters made wooden mills. And they’d grind that molasses and they had a vat, big kettle to make it in, you know, had big fire put the kettles on. And when that molasses was made, they had a big long trough to pour that molasses in. No barrels at all. I never seed a barrel then, nothing but long troughs. And when you get your molasses made, they had plank to cover them troughs.”

Jonah went on to tell them more about his experience with slave labor, “Now, now when I was a boy, they used to make soap. Well I was large enough to tote water to the soap makers to put on ash hopper. Now they didn’t have no barrels, they had boards, you know. And uh, them boards come in that-a-way,”

Jonah pointed off to his left, “You know.”

Then he pointed back to his right, “That-a-way, them boards was there. Well, all these here, and you’d lay some crossway to hold the ashes. And then I’d tote water and put on that ash, ash hopper for the soap maker. Now he’d make soap for the whole plantation, and uh, make about two or three times a season. And along then, I ain’t seen none, no bar soap. They might have had some at the big house, but I never seed none.”

Jonah asked, “Guess what was the worster job I’s remembers.”

No one answered right away so Jonah told them, “And had, uh, something dug in the ground, hole, deep hole and board up on each side, it was plank. Well, it was about three-foot-deep, I reckon, and about eight or ten foot long. Well, they tan leather. You smell if from far off, is bad, bad, nasty, is nigh as I can come at it, but I knowed right where it was and which way to walk.”

There was an unmistakable expression on each child’s face, something did not smell good. Laughing together, they traded unpleasant sounds between each other and kept listening for what came next.

Jonah told them, “They’d lay a, lay a bark down in that hole, and then they’d lay, lay a hide over that bark. And then they would lay another layer of bark and another layer of hide, till they got it like they want. And then they’d fill that thing up with water. But now, before they’d tan that, that leather, they had to let it lay a while and get the hair off it. And when they got done with that leather it’s just like any tan leather, and they had a man there to make shoes for all us. Now we was children, good size children, going about, that shoemaker make shoes for we children. And the old folks too. Was my first shoes, Jonah shoes.”

The next request came from one of the older boys. When he asked his question, it sounded like the young lad had a big chip on his shoulder. “They treat you pretty good?”

“We had mighty good white folks, my memory, far as I can remember, you know, mighty good, mighty good,” Jonah answered him with confidence that he was telling the truth.

“You know they must have been good. Yes sir, they treat me nice. They treat me nice as they could treat me. I’s came up here, over here, from Texas to Pennsylvania, United States. An’ they all treating me mighty nice, all the white folks that know me, they treats me nice. And if I want anything, I’ll ask for it. I was taught in that-a-way by my old master. Don’t steal, don’t lie, and if you want anything, ask for it. Be honest in what you get. That was what I was raised up with. And I’m that-a-way today.”

One of the boys put some more sticks on the fire, and while he was stirring the ashes, he asked, “How were the black people mistreated back then in slavery times?”

Jonah paused again, and he looked at his pipe; he glanced at the fire and back to his pipe. He did not want to go here or what to say next, and he was trying to avoid saying anything that would upset his grandchildren.

He saw no way out of answering the question, so he said, “I know of times they, when, when they mistreated people, they did, and I hear our folks talk you know, about them whipping you know, till they had to grease their back to take the holes from the, the back. Good Lord have mercy. That was bad sure. Them white folks were that a way. But master sure didn’t allow his colored people be whupped, no how. They use the whip on, horses and the ox, not ever hurt his coloreds. Not ever hurt colored folk.”

All the younger Godfreed children wanted to know about their grandma. Chunky was the only one that dared to ask his papa, “You haven’t told us anything about your missy wife?

It got real still then. Everyone that had been up listing to Jonah all night had noticed he avoided talking about her. The silence was deafening.

Then he spoke very sharply, “She dead too soon.”

As his own words sunk into his memory, the older man became young again as he thought about her.

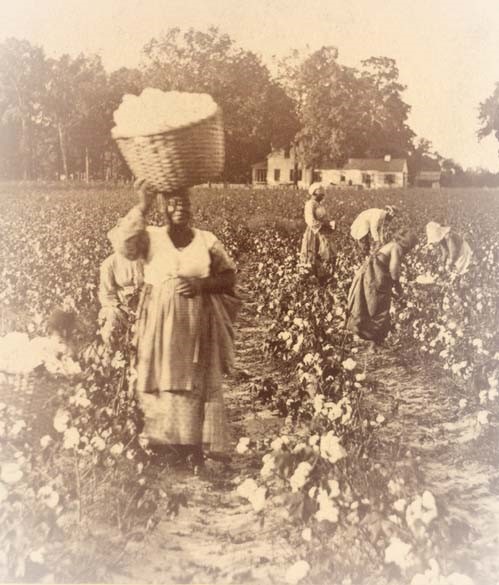

“She good as any man, can plow and lay off a corn row as good as any man. Chop, and chop, pick cotton. She pick five hundred pounds of cotton. Knock out five hundred pounds. Then walk across the field and, and hunt watermelon, pomegranates and such. My missy, your grandma, was in the big house. She house slave.”

Jonah poured out his heart that was full of good memories of his missy, “My missy, she take care of the children. In the morning before sun, getup, put on the cereal, and stop and wash the children hands, brush their hair. She would put the tablecloth upon the table. And get the mat and put them on top the tablecloth. Then get this knife and fork and plate, put them upon the table. So, when missus and master and company sat down eat. Then she and the old woman feed all the colored.”

Someone asked, “Out of all you told us tonight, what do you remember the most dear to your heart.”

Another voice, “What is your fondest memories of the older days.”

And yet another, “What else did you do when you were our age?”

Jonah was, all-ready, with his answer before they had finished asking their questions. But his response was just not what they had expected when they asked him. He had lived, and survived, and grew up living as a slave. He evidently had seen more than what he had already shared with them. Their curiosity had the best of them now.

Jonah interrupted the line of questioning and said this, “The thing I’s member the most from all that bad happen, the thing most dear to my memories in my heart, most important thing I learned, I teached to you now. The Lord Jesus loves ya, he was always there for me, Him there today, right now, and He there for all of you too. The most valuable possession I’s still have with me today from my boy times, is my talk with Jesus.”

Jonah took a toke on his pipe, and another, and another, and finally got it going again. But the weed had all but ran out, and now there was nothing left but hot ash glowing in his pipe. With little effort, he was reloaded, puffing and spitting out tobacco and his story in one motion.

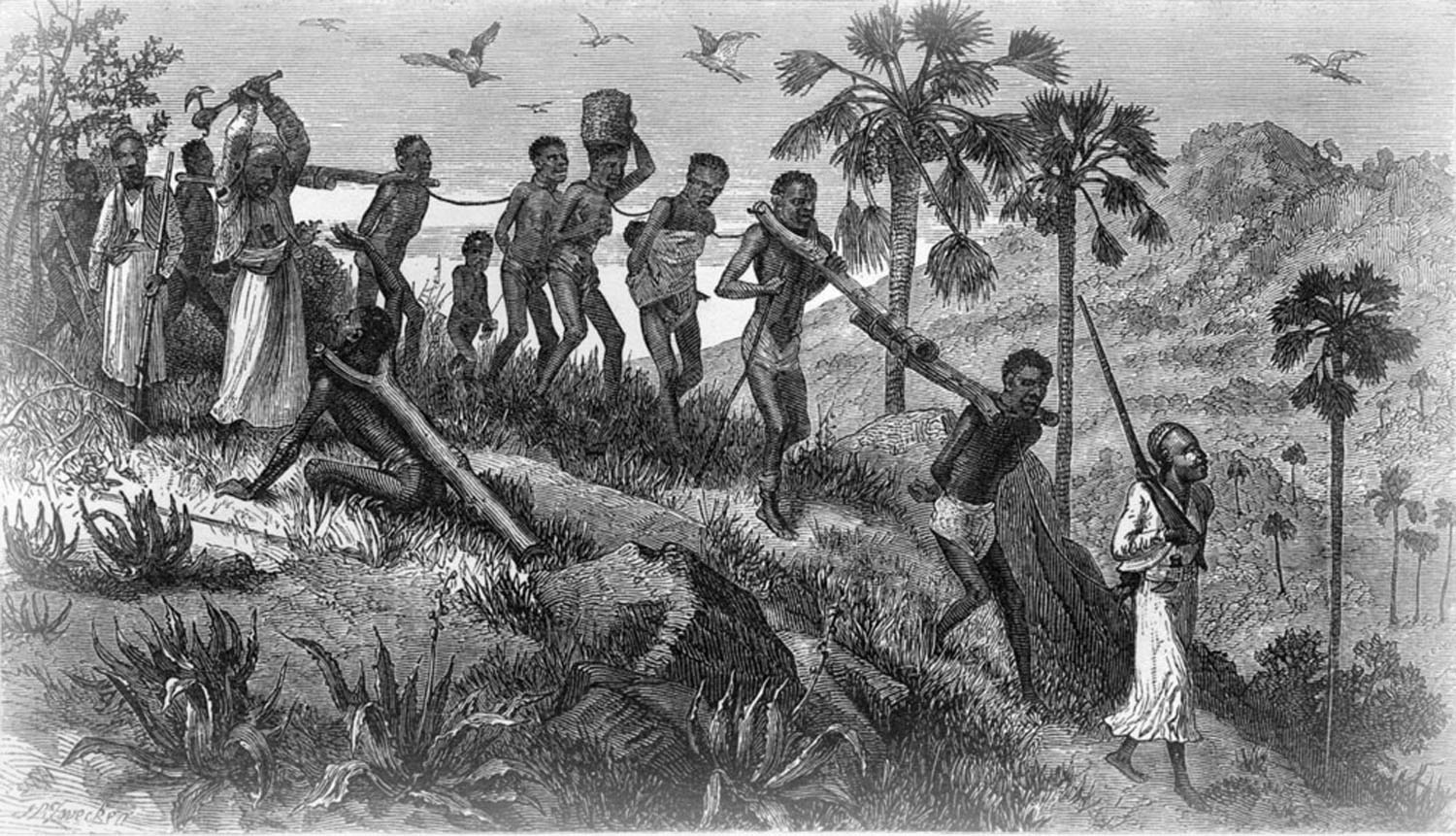

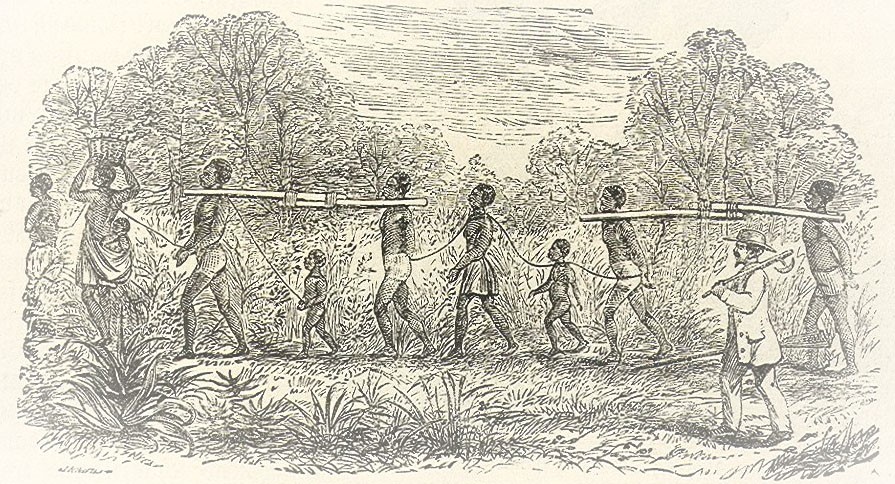

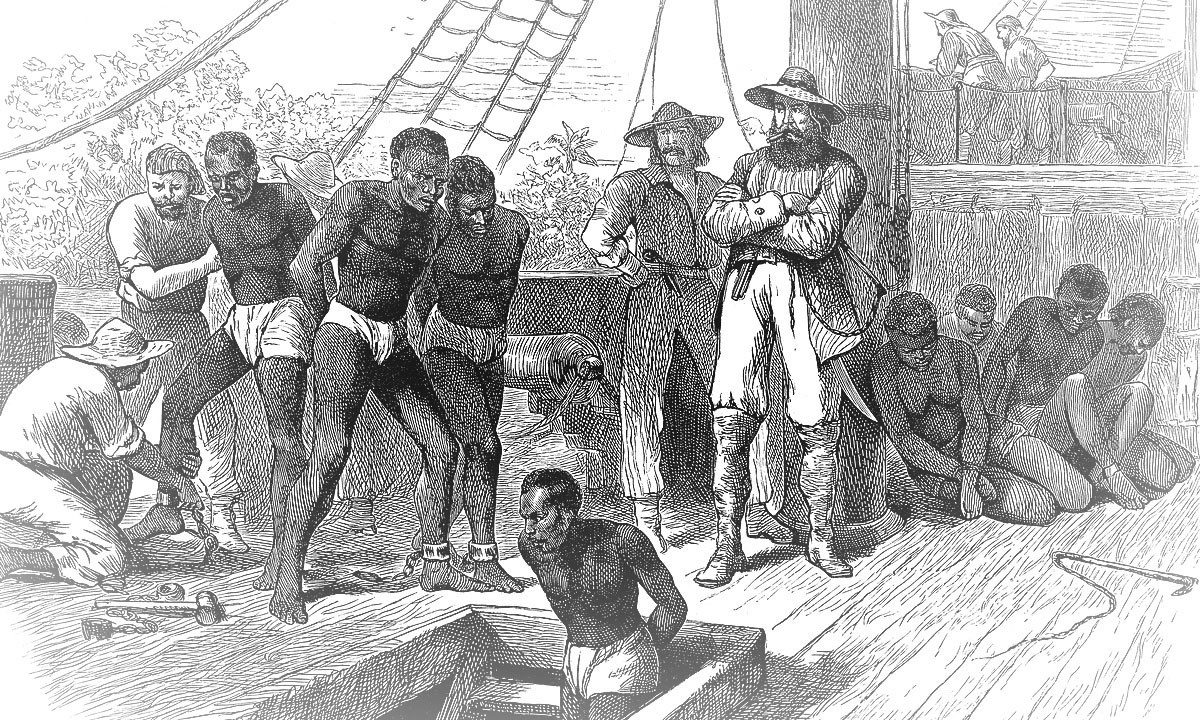

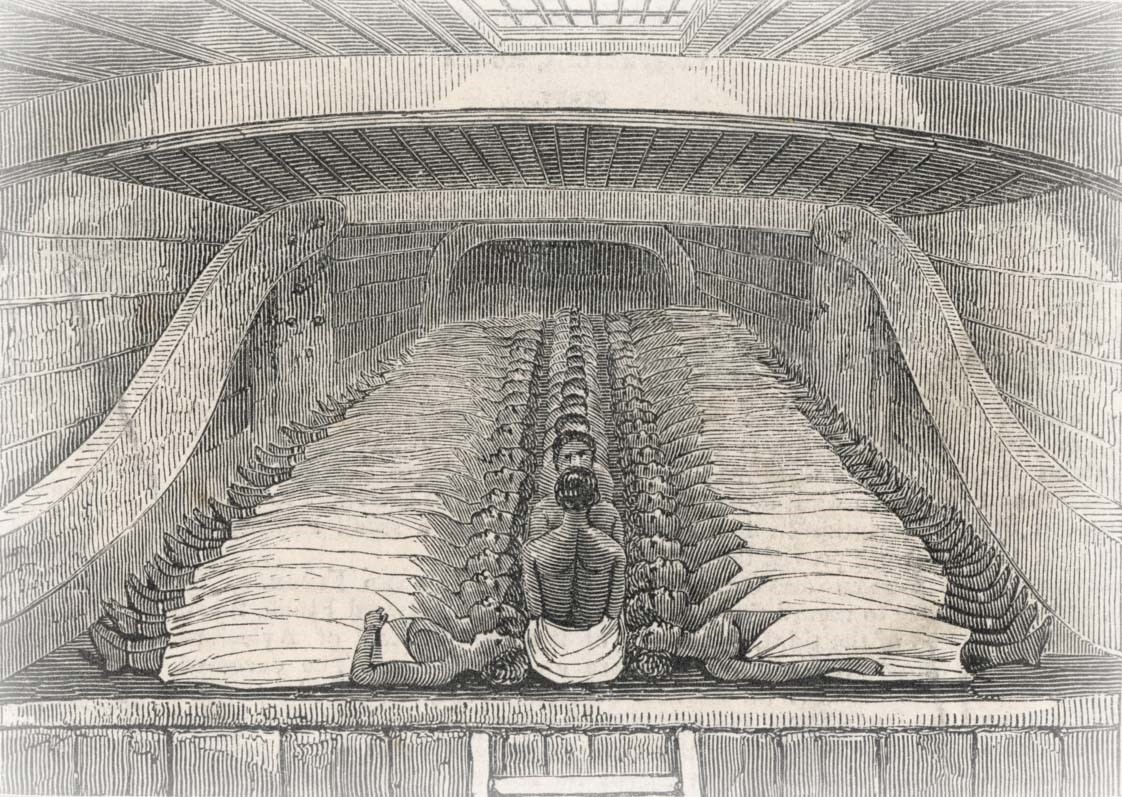

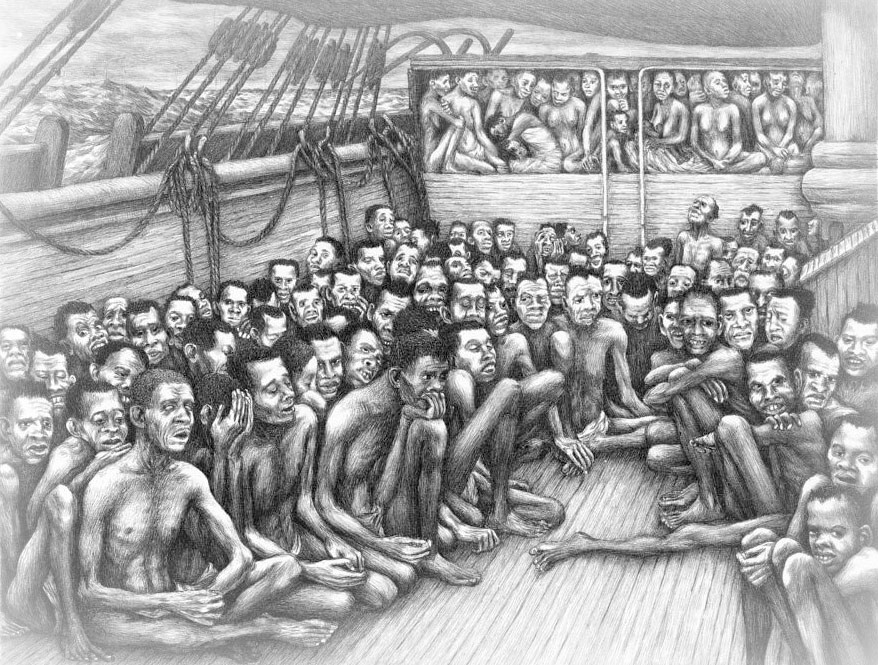

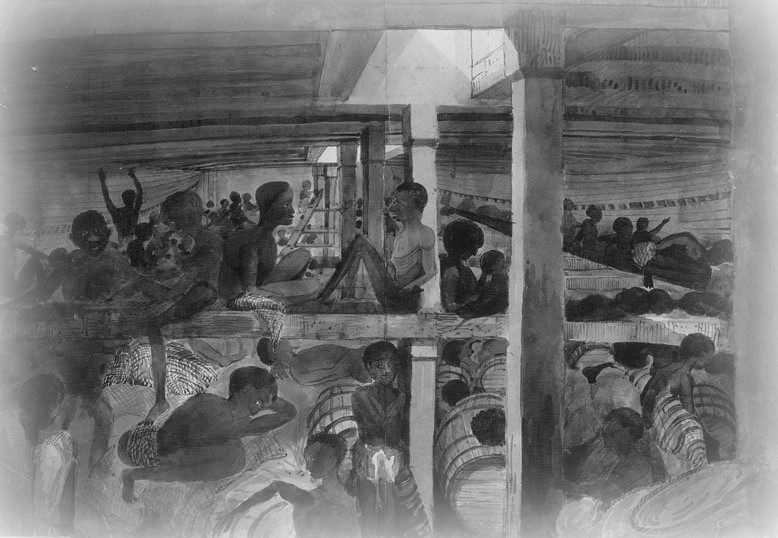

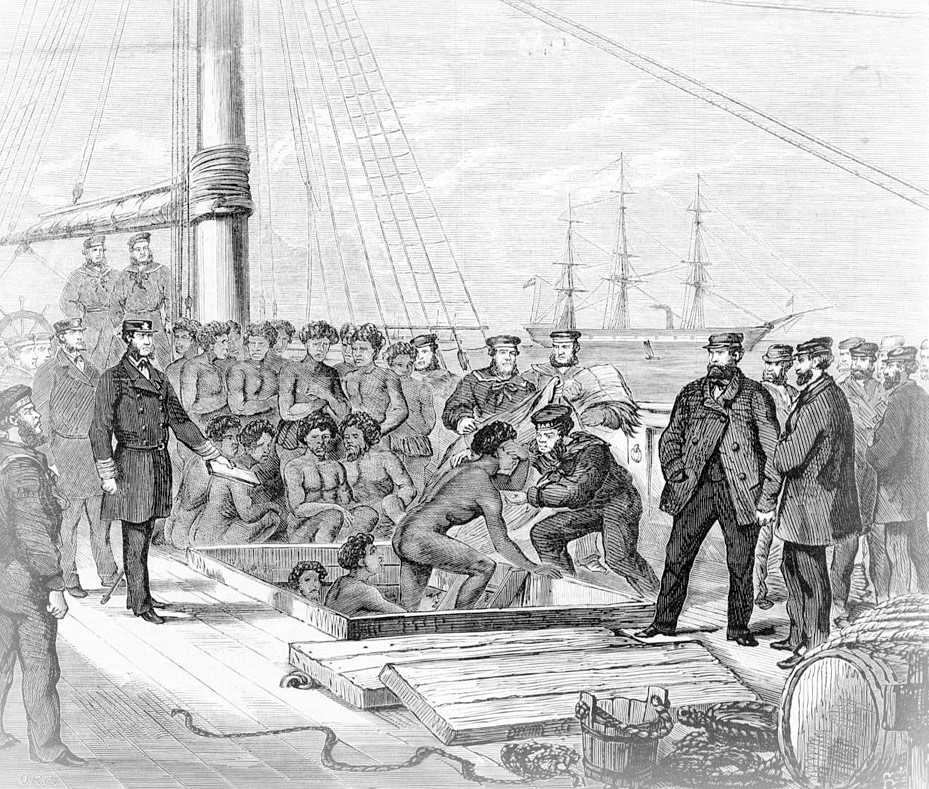

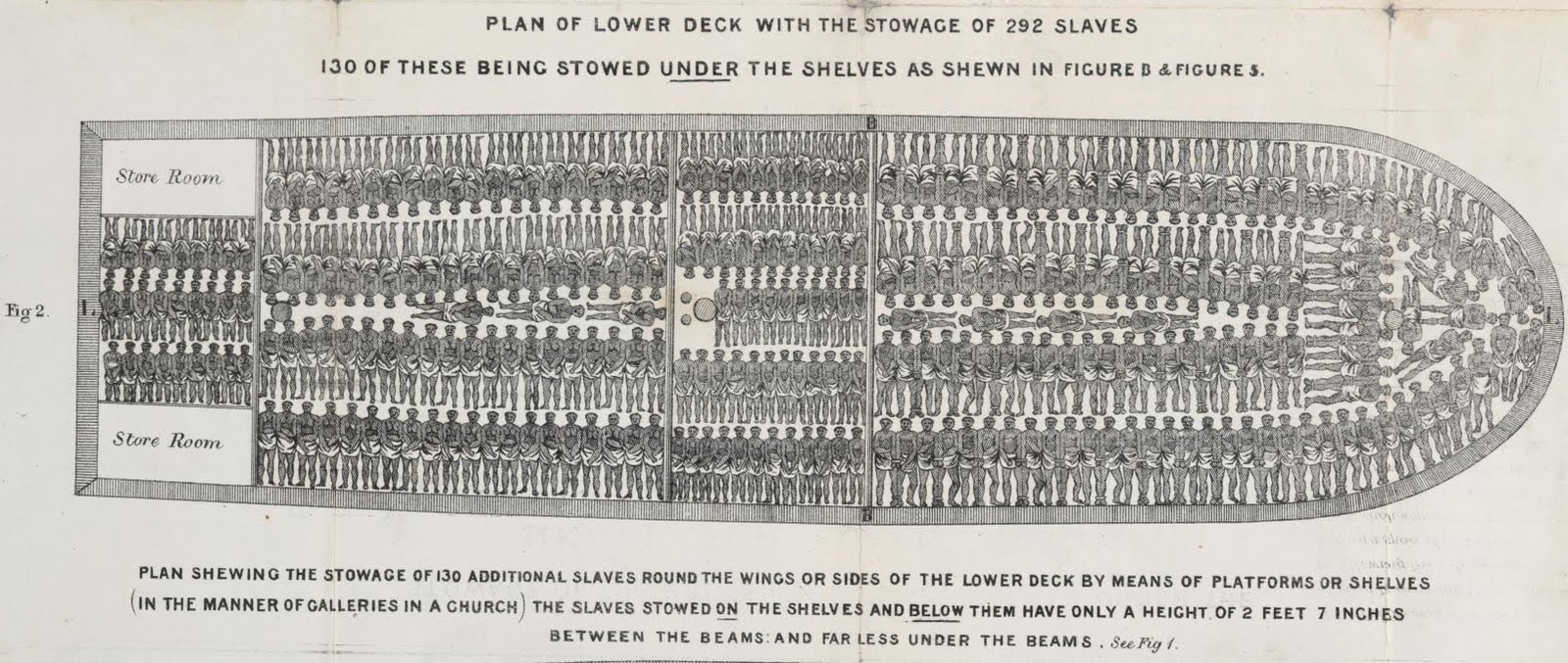

“I was born in Africa. I’s born a slave to my mama, she was slave to Black men that sold colored men, woman, children, to white sea captains on big ships. They bring us New Orleans, United States to be sold. Black men started me a slave. Black men stole colored people from their home.”

With anger in his eyes, Jonah said, “Black men put me in chains, and get to the white sea captains.

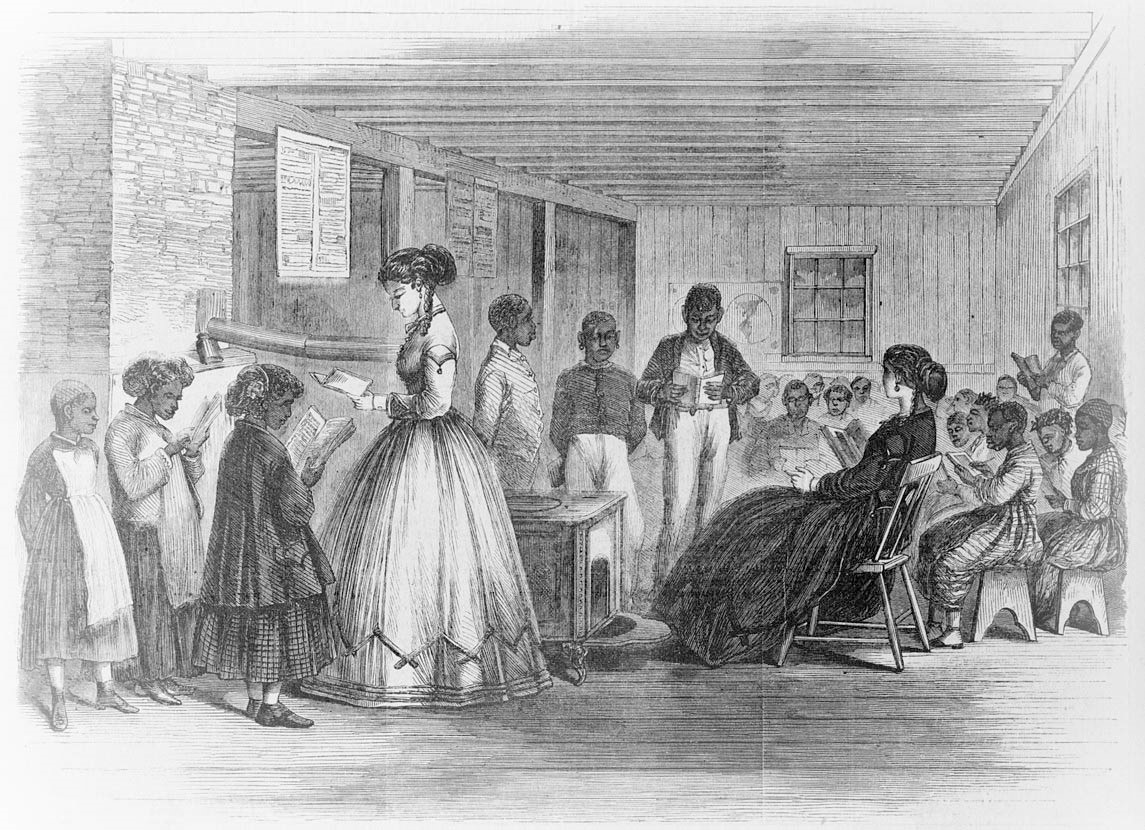

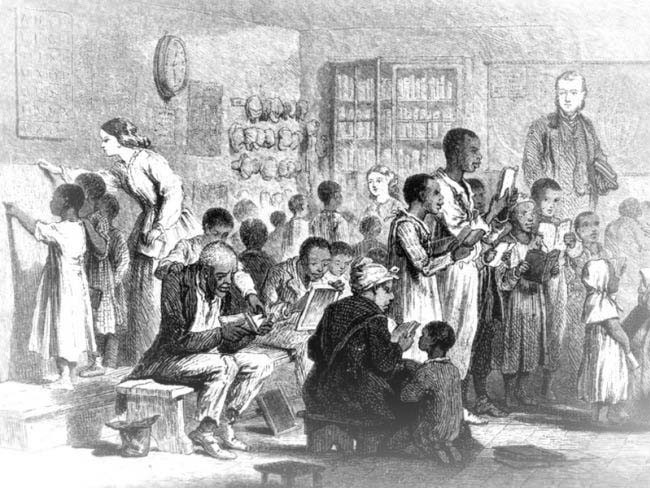

There was some white folks that in slavery that teached us about Jesus. We did not understand, just want to be free from slave. So, we believe the stories. I’s pray just like they did. And I’s know Jesus going to hep me not be slave. I’s always talk’in to Jesus.”

Jonah preached to his grandchildren, “I’m telling you now we ain’t nothing without the Lord. Got to put our trust in Him that gave us. That’s the onlyest way I’m still walking round today. I trust the Lord will bless you all. You all hold onto the best you can while we live. Take the Lord with you.”

Jonah began to clap his hands and sing. “Ever hold you hands in his?”

Then he hummed a few lines. “I would say, get in trouble, all you got to do is call Him. See! Only one you can call.”

Jonah sang a little louder, “Yes, sir. Call Him. Call Him. That’s all of you. And this young lady right here, you know,”

Jonah leaned over and hugged the child under a blanket that had been leaning on him for a while to keep warm. “I know ah, you all’s buddy, that’s why I come up here tonight talking to ya. Talkin about slavery time and all. Great God almighty there’s our Lordy up heaven there.

Him name Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. He fix’in a great place, gold roads, nobody hungry, no body hungry. Colored folks, white folks, all be gathered as brothers and sisters, brothers and sisters in Christ. Swing low sweet chariot take me home to Jesus.”

He was all wound up now, and Jonah told them, “I’m telling you now, our people got to do right in the sight of God, because he knows all about us. And I’m, and I’m so thankful. And I tell you, young people these days, the young folk, the young folks ain’t taking the time. Is ya?”

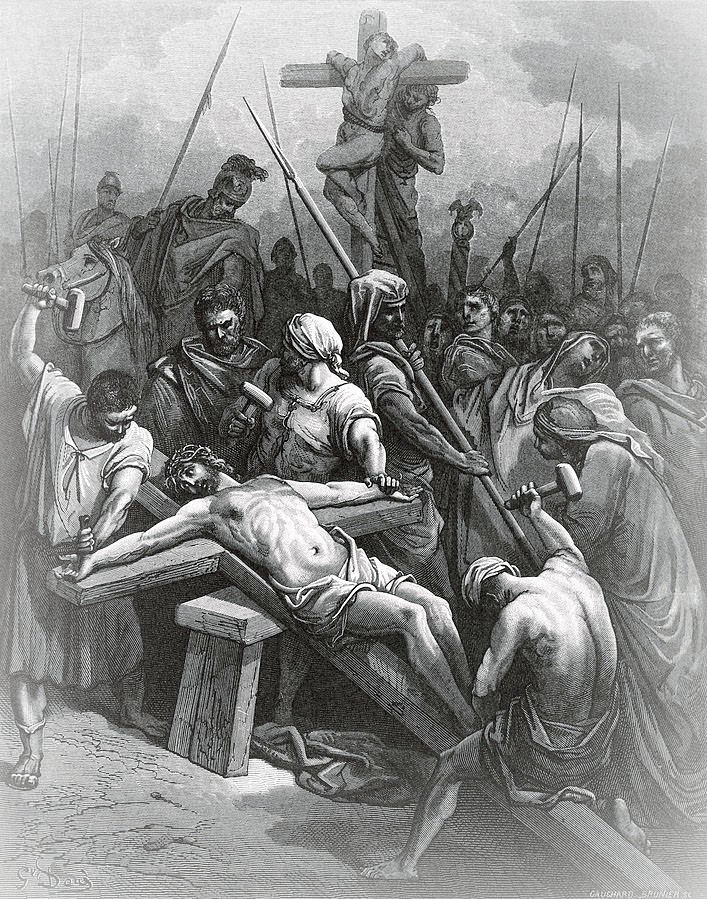

Jonah looked around to see if everyone was listening to him, “Time to read the Bible, those that read, those that read can teached those that ain’t read no how. For God himself up dar in heaven, he sent his onlyest boy child to be a slave down here on earth. He dead on a cross of wood, piece of a tree, then used them big-o-nails put thru hands and feet on him. He died to set all the slaves to sin be free men and woman.”

Jonah opened their minds to the blessed assurance that, “Now, all we-all do here and now, is believe, believe, just in what he say down in his Bible book. Younglings dat taking the time, read that book, knows what God want. All people’s book. All people’s book. For them.”

Jonah’s ability to remember the past was picking up speed. He found himself like a preacher man on Sunday morning. He looked out at his gathered congregation and said, “I was at ah, a white man church, and ah, a man got up to speak. You know, we never heard the sermon preached before, bout dry bones.”

One of the girls said, “What about bones?’

Without answering her, he kept his story going saying, “The man couldn’t even speak, until they wanted him to. So, when he got put up on a bench, up front, he come there to speak, I take notice. I take notice, in that big Bible book in his hand. Preacher man say he talk bout dry bones in that Bible. And we ain’t know nothing bout no dry bones. Preacher man says God gave us, the Lord’s ten commands. Lord is coming. Yes, sir, that day is coming. That day is coming. That day is coming, and we got to prepare that day.”

One quick look at the children, and Jonah saw they were all still listening. He said, “Now all us knowed God gave us, the Lord’s ten commands. Yes sir, we all knowed Lord is coming, we just want to know bout dry bones in the Bible.”

The preacher man went on to tell Jonah, “That day is coming. That day is coming, and we got to prepare that day.”

Jonah said, “ I want to hear the first trumpet when it blows that morning. God, gave us commandments, Lord. God gave us Christ and he taking us all home to heaven.”

Then the preacher man said, “God raising the dead, and how the Lordy his self, have to come and pick up all our dry bones. He raise to heaven all the dead folks.”

Relieving himself of a little chuckle, Jonah grinned, “We all just bust’in at the seams of our britches, laughing at that preacher man’s talk bout dry bones.”

Jonah went on with his sermon, “Well, I tell you don’t people, don’t, don’t pray like they used to. They don’t care so much for it. Who is we all without the Lord? Hmm? He hold us in the hollow of his hand. All power in his hand. But the young ones is forgotten that. Yeah. But I’m telling you myself. And then they shame, they don’t, don’t honor him like they ought to. I pray up to heaven, please don’t lock the door. Jonah is coming, Jonah is coming. The witness is in our breath. The witness is in our breath.”

Jonah picked up a bug with a small stick, and he surprised everyone when he put it into the fire. “Judgment is near at hand. It’s near at hand. It’s written in the Bible. Time ain’t long. Do you believe it? I said, Luther, you can go right ahead, be dat Satan. But it’s the truth, but God are going a put a curse on you. And I say, you mark what I tell you Devil man.”

Someone asked, “Tell us about when you were a little baby and a little boy.”

Jonah just laughed, “Oh, when I’s was a baby I, well I, I’s couldn’t remember nothing. I couldn’t remember nothing from when I was a baby. No sir.”

That remark got a big chuckle from the peanut gallery. Jonah took a toke on the pipe, and the smoke came out his nose as he started talking again.

“Back when we was children, you know. Wasn’t able to, to, tend to no, tend to no other children. I had a older brother though, he could tend to children. In the, you know, just sit them down in a corner and put this child, you know how little children, put this child in between his leg, and then hug his hand around this child, that’s the way he nursed them. Couldn’t stand up with him. Couldn’t, you know, just enough, you know, shake him this way in the arms.”

Jonah pretended to be cradling a baby in his arms. “I, I can remember that. I had a brother, name, Willard. And he just shake that child so gentle like in his arms. Set him in the floor sleeping. And he, and if that child kick much, he’d fall down and play dead, kick him over too, you know, and catch him in his arms and hug him big time. Willard he got tick fever, mostly die, he can’t do too much no how sept baby keeping.”

The girls were talking among themselves, and finally, one of them asked, “Who fed the babies?”

Jonah explained to the girls, “They had certain times to come to them childrens. I think about this like a cow out there will go to the calf, you know. And you know, they’d have a certain time, you know, cow come to his calf and at, at, at night. Well, they come at ten o’clock. Everyday at ten o’clock to all them babies. Give them what nurse, you know. Them what didn’t nurse they didn’t come to them at all, the old lady fed them. Them wasn’t big, wasn’t big enough to eat, you know. She’d ah, the old mother had time, you know, to come feed um. When that horn blowed, they’d blow the horn, for the mothers, you know. They’d just come just like cows, just a running, you know, coming to the children. Out of the fields. Out of the fields. I don’t know how old they, couple years, till it was big enough to walk, I guess.”

Another one of the girls asked, “What bout when the babies get hungry at the night-time, did they feed them?”

Jonah answered, “Yes, ma’am, twice a day. Come there and nurse that baby. He couldn’t eat, you know. But one dat could eat, he wouldn’t come until dinner time. But little one what couldn’t eat they’d fed them in the shade.”

Chunky had a great interest in his father’s past. He had already retold some of the stories to the younger ones in his family, and his favorite ones were about his papa when he was his age. So, he asked Jonah, “Did you mama pass down any stories about you when you were our age?”

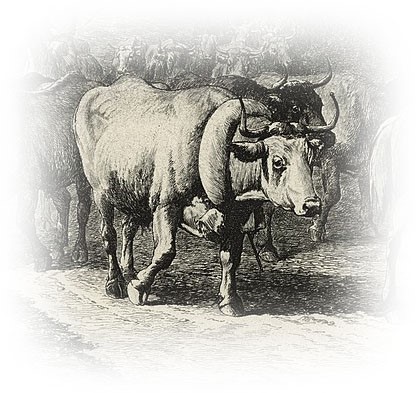

“I remember when she used to tell me about the day when I’s was uh, little sprout and used to ride the oxen and things. Yeah. Oh, my papa drove some, the big old oxen. He had one with, uh, big with wide horns. Oh, looked like a house.”

Jonah seemed to slip into a second childhood as he described his childhood experience. He even got down on his knees to make himself shorter, as he encouraged his listeners to believe he also once was young.

“Wide horns, and, and, and I used to set up there in between them horns. And he, his name were, Old ’Steamboat. His name Old’ Steamboat. He named Old’ Steamboat, cuse when it be frost cold, the steam shoot out his nose like the old river boats smoke. The other ox him name Samuel.”

“And papa drive them to church that day. And put da children in the, in the old, old ox wagon and carry them there. And, and I’d get up there and on, and on, and on Steamboat, clinging on Steamboat horns, and sit up there. Sit up there just as big as I was setting in a house. Him back so wide, so big, I could lay down all flat and nap a while.”

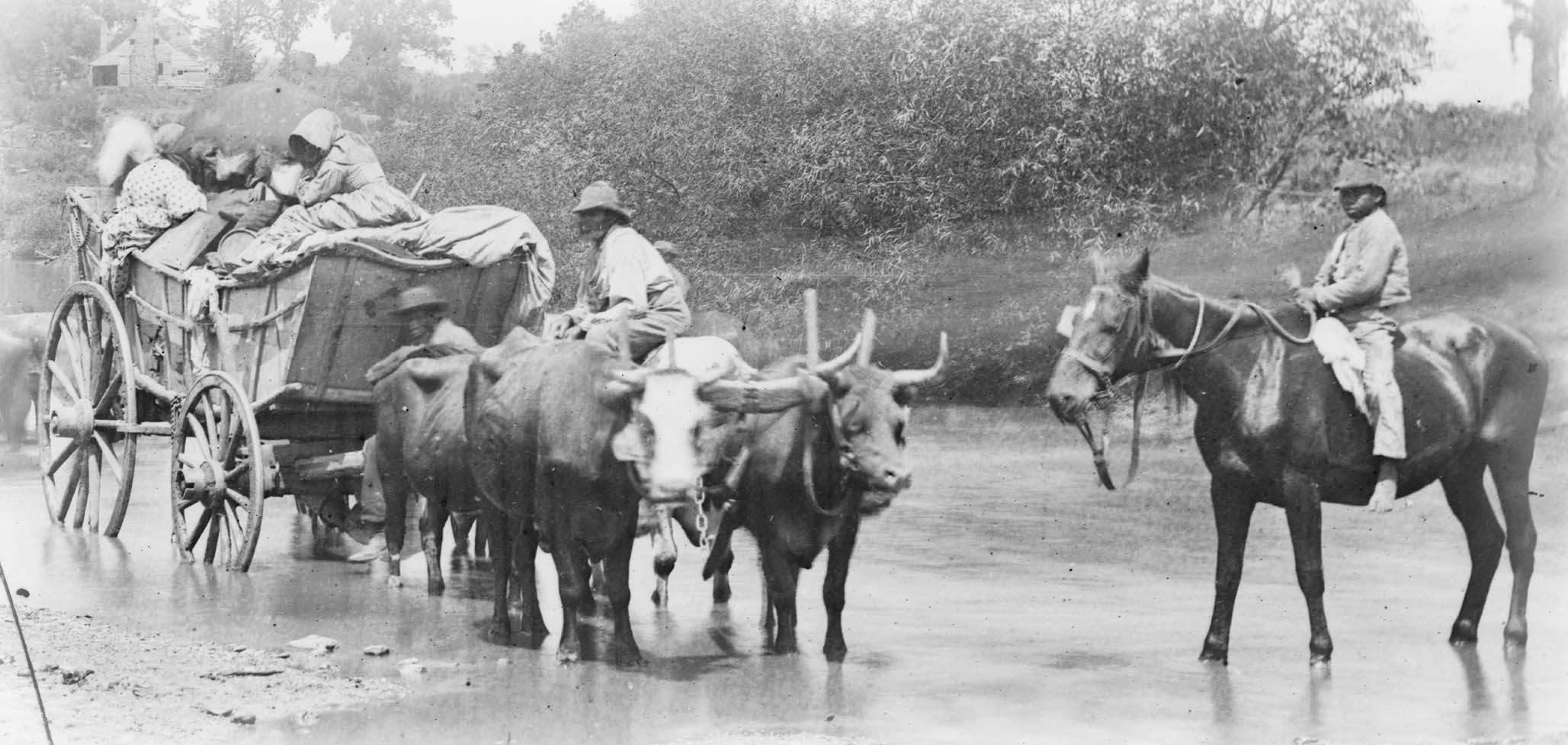

“Well, papa went to, went to, to lumber. Want to get some lumber, and he had to go cross the river. It was in the summertime, about the same this year, in June, and the, the, the old oxen got hot. They got hot. Oh, and then, uh, when we no knowed anything, papa knowed anything, them old oxen done run off in, runned off in the river with us, with us, with that, with that wagon.”

“And, and there I sat up there in the old’ Steamboat horns. Sit up in old oxen horns. Oh, and he’s wading through the water, and I was setting up in there. I stayed in there too. I held to his horns. I held to his horns. I didn’t fall off in the river. I held, I’m telling you, I held it too, yes I did. Oh, oh, my papa was just a whipping with that whip, trying to get them out of that uh, river. And we was, and old Steamboat and Samuel was coming through. They come out too. Yes they did but not till they got good cooled, and a big drink. They no move till done gettin big drink.”

Someone asked, “Jonah, what was the worst thing you can remember about those days.”

Some things a person experiences in their own life are too bad to remember. From some experiences, we learn a more important lesson from going through it, and it should never be forgotten. Jonah tried to walk the very thin line between the two, when he spoke about the past, to his youth of the feature.

“Some white folks hurt bad the colored folks. I’s don’t, don’t much like talk bout dat, couse have to think bout dat slavery time, slavery time bad for colored. My eyes see bad, bad thing one day. Remembers a hanging. But ah, ain’t nobody know what the man done or nothing. Ain’t nothing at all about it. And they hung him. They tied and hung him. I went to that place, they were hanging a boy, standing there looking about was, his mama, brothers and all, out yonder held back by the overseers.”

An older young lady asked Jonah, “Did you watch someone get hanged?”

Jonah answered her, “Yes, ma’am, I stood and looked. And the, the, a gallows was up as high as here covered this house, and got all the people all out the field coming around all standing in line. And this, this, this boy standing their rope around his neck. And ah, I tell you that’s something for you to look at. I don’t know what I ain’t seen in my life. Terrible sight I know. And when they got ready to touch the lever, and when they touch the lever, that boy, that he had the rope around his neck, and they just caught him hanging by his neck. I’m afraid that believe your eyes. Believe your eyes.”

There was a sudden burst of questions all at once, but the voice that was the loudest got an answer, “You say his mother was there?”

Jonah replied, “Mama, father, brother, and all right there in the line. Overseers make them in the line, so they can watch good. And I never saw such crying in all the days of the Lord. And I’m telling you, start living on the Lord. And, I’m just telling you all. They say he moves in mysterious ways and his wonders are many. And he plants his footstep in the sea. And he rises up on the storm. And when this storm come, there was, this boy they hung, and they say there was a hundred men, right around here just to see. And they, they, they would not bury the boy. They burn him up. They burn him up. And they had to burn the boy up by tonight you see, you see, you see. And all the people stood and watched till dark.”

Everyone kind of knew that after so much time, one of the girls would ask, “Tell us some more about our grandmother, please.”

No one ever heard of any other name for her, other than what Jonah always said, “My missy.”

That question, strangely, was avoided by all and was not being asked by the young listeners. None of them asked because that’s the way they all remembered her, “My missy.” She had died long before any of the children were born.

Once again, Jonah’s attitude abruptly shifted, back, back to an intense sore spot in his memory. This was why he did not like to talk about his life as a slave.

>>>Click here <<<

Next: The Chunky story – part 2 – picture book – 2