Rebel soldiers on the retreat

There was no time now to think about anything but trying to stay alive. As it so often happens in the fast-moving tide of war, the battle lines shifted, and the Rebels were forced to make a hasty retreat in all directions. The only men left in the yard were like David, unable to move without help or dead. The change in sides came so quickly all David noticed was the uniforms went from grey to blue, and soon the Union medics were treating his wounds.

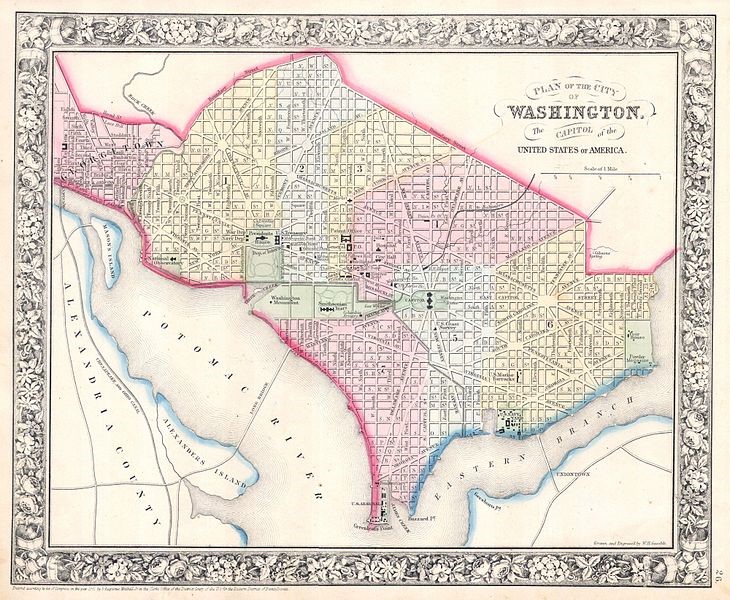

Washington DC

He was pleased that the bleeding had stopped on its own. The mud had caked over the wounds like a clay bandage. It probably saved his life. One bullet had gone through his right pant leg, leaving a hole. But the other bulled had hit him in the left knee. The corpsman dressed and bandaged his wound, then he got David back on his feet, able to walk a little again.

A wounded Civil War soldier resting in a deserted war camp

The Doctor ordered him to be sent to Washington, where under kind treatment, he sufficiently recovered to return to light duty. After the rebels were repulsed, David was ordered to the War Department barracks. He did duty around the old Capitol Prison and the Navy Yards Prison, where Mrs. Surratt and other accomplices of Pres. Lincoln’s assassination was confined.

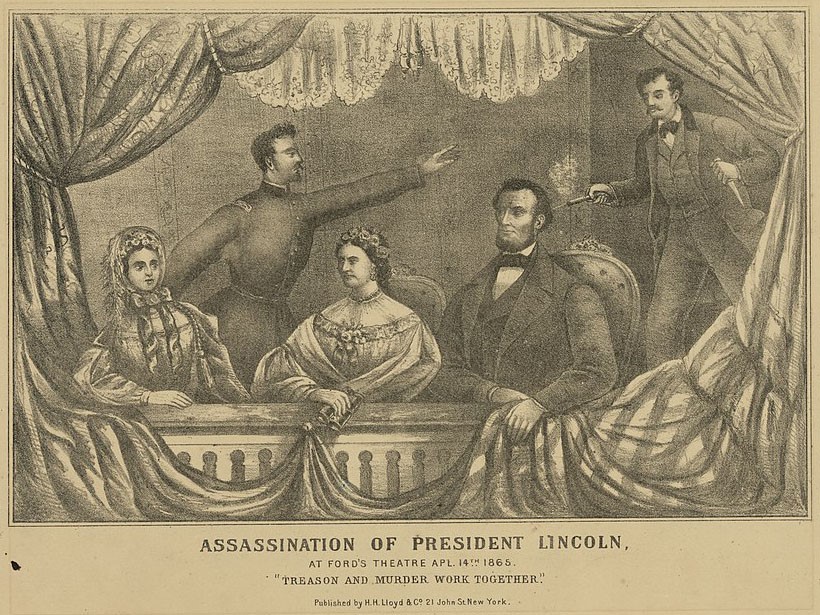

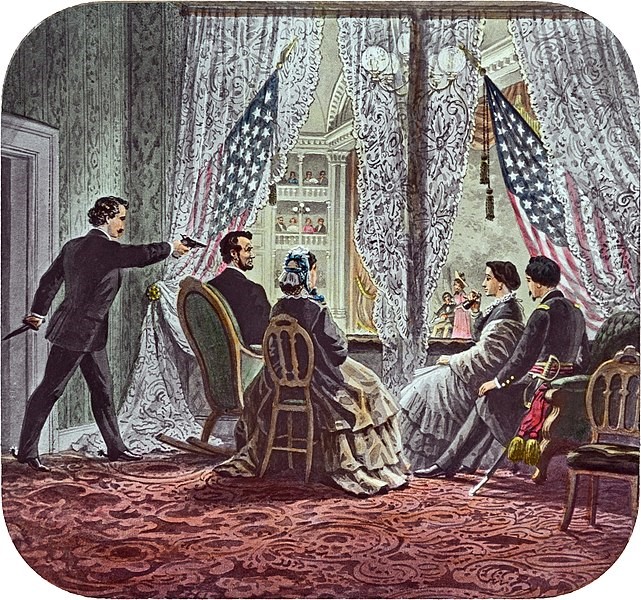

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on Good Friday, April 14, 1865. He was attending the play “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., just as the American Civil War was drawing to a close. The assassination occurred five days after the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army of the Potomac.

Booth’s co-conspirators were Lewis Powell and David Herold, who were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt, who was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson. Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to disrupt the United States government by simultaneously eliminating the top three people in the administration.

Booth’s co-conspirators were Lewis Powell and David Herold, who were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt, who was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson. Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to disrupt the United States government by simultaneously eliminating the top three people in the administration.

The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln

As the President was watching the play, Booth shot Lincoln from behind at a distance of perhaps three or four feet, hitting him in the back of the head. At 7:22 a.m. the following day, Lincoln died in the Petersen House across the street from the theatre.

Powell only wounds Seward

The rest of the conspirators’ plot failed; Powell only managed to wound Seward, while Atzerodt, Johnson’s would-be assassin, lost his nerve and fled. Booth made a dramatic escape, resulting in a lengthy manhunt that ended in his death. Several other conspirators were later tried and hanged.

The convicted

The regiment was mustered out of service, and on its arrival in Easton, the Colonel shared in the great ovation. The occasion will long linger in the memory of the survivors. The pleasure of the reception was significantly increased by the incident of the presentation of a beautiful sword, the gift of the officers and members of the regiment.

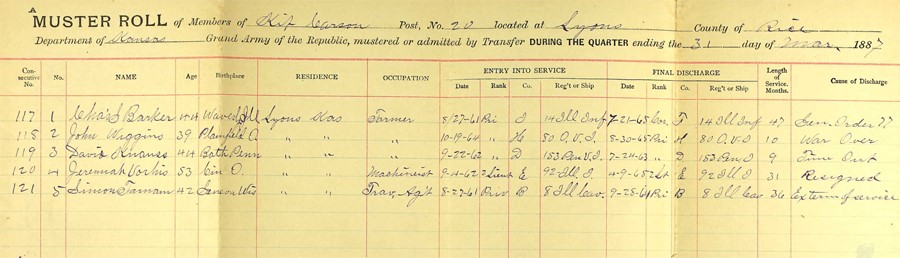

David Knauss mustered out of service

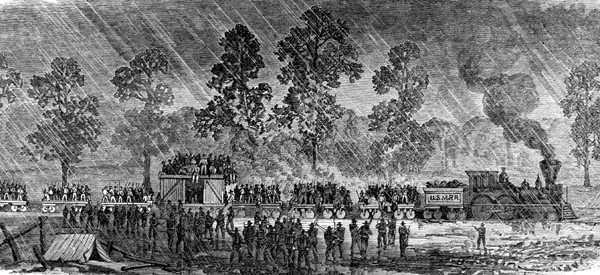

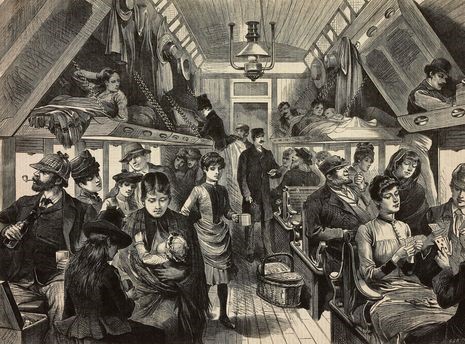

Boarding the train

David and the troops boarded the train for Philadelphia and arrived at about 9 o’clock that night. Here they got tasty meals, had wounds dressed, but instead of taking a cot as the rest did, he lay down on the floor. About midnight, the fellows commenced getting out of their cots and, complaining of backache, took positions on the floor. The beds were too soft for an old soldier. That night and the next morning, the trainload with which they came was sent to West Philadelphia.

Sleeping on the floor

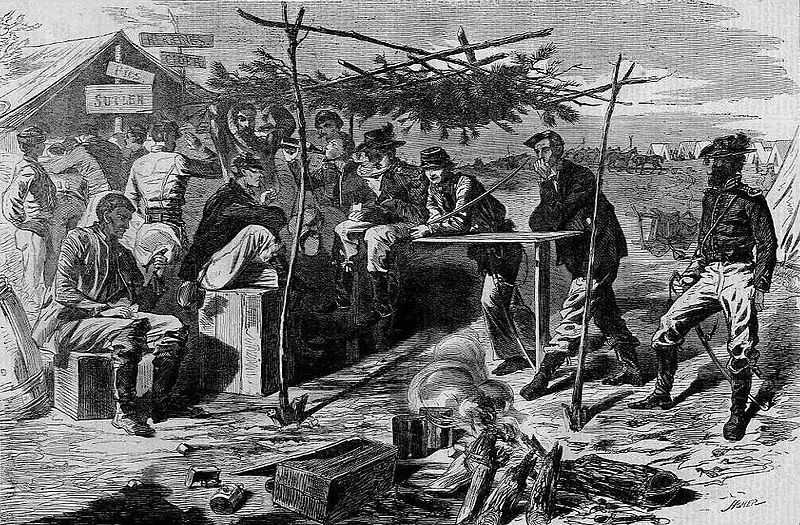

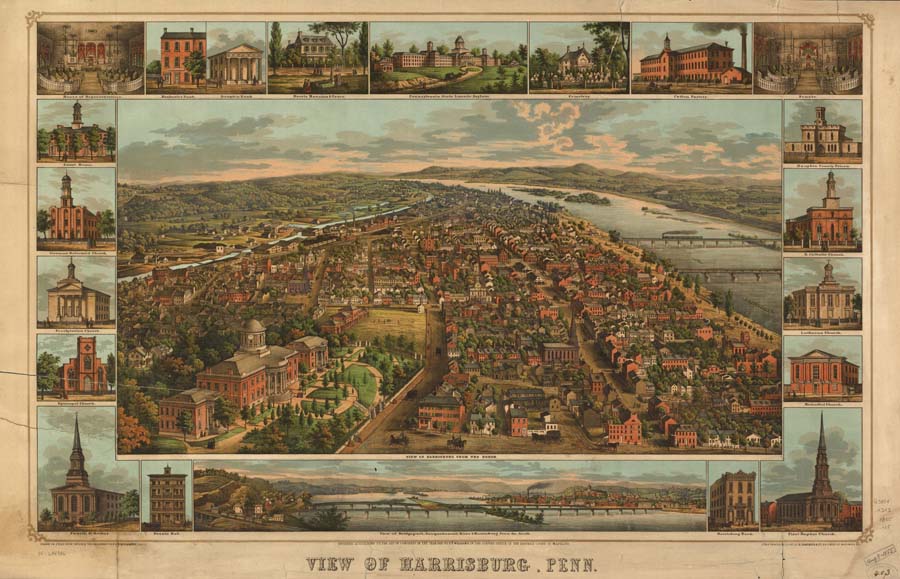

The men, twenty in number, belonging to the 153d Regiment, requested to be sent to Harrisburg, and their request was granted. After reporting to the general hospital, where they got dinner, they left for Harrisburg, arriving there that night at about 9 o’clock. The first thing they looked for was Uncle Sam’s boarding house, known in wartime as the Soldiers’ Retreat.

Harrisburg station

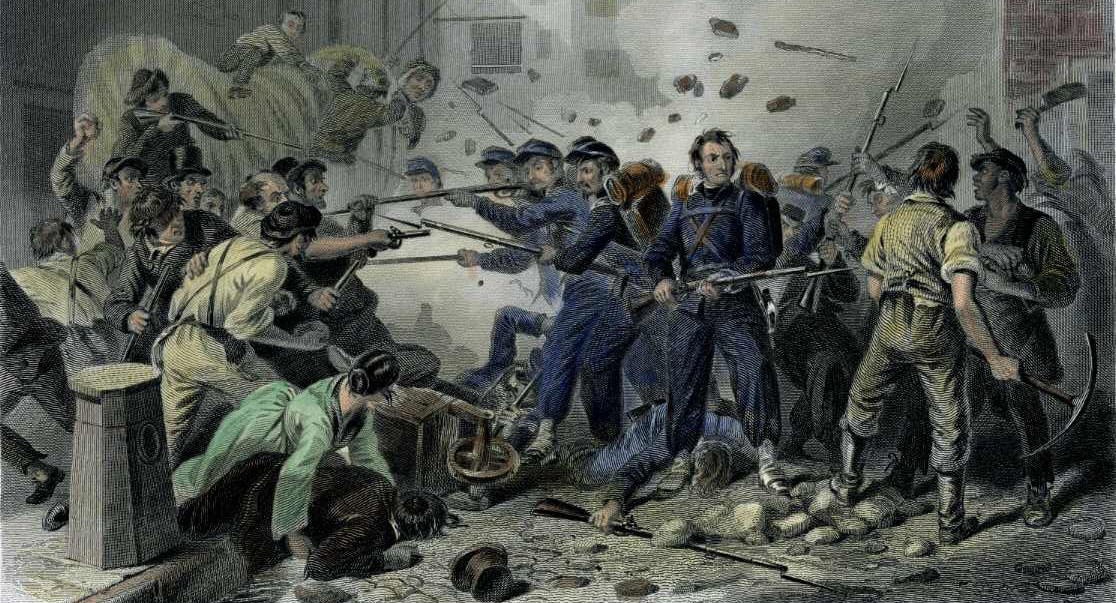

There was one corporal in the squad, and he was sent to the mess hall to see about supper. He returned and reported that the man in charge said that they could not have supper because he was expecting a militia regiment that night. David’s crowd was composed of twenty men and a corporal. All the men looked ragged, bloody, and dirty—some with heads tied up, some with arms in slings, some with crutches and canes. In fact, they looked as if they had seen service, had been to the front, and this report was not acceptable to any of them.

So, the men held a council of war, and it decided that they storm the retreat. There were two or three old pistols and revolvers in the crowd, but none of them were loaded. The men had no trouble with the guards, for they were on their side. The guards quickly passed them, and they got right to the front of the line.

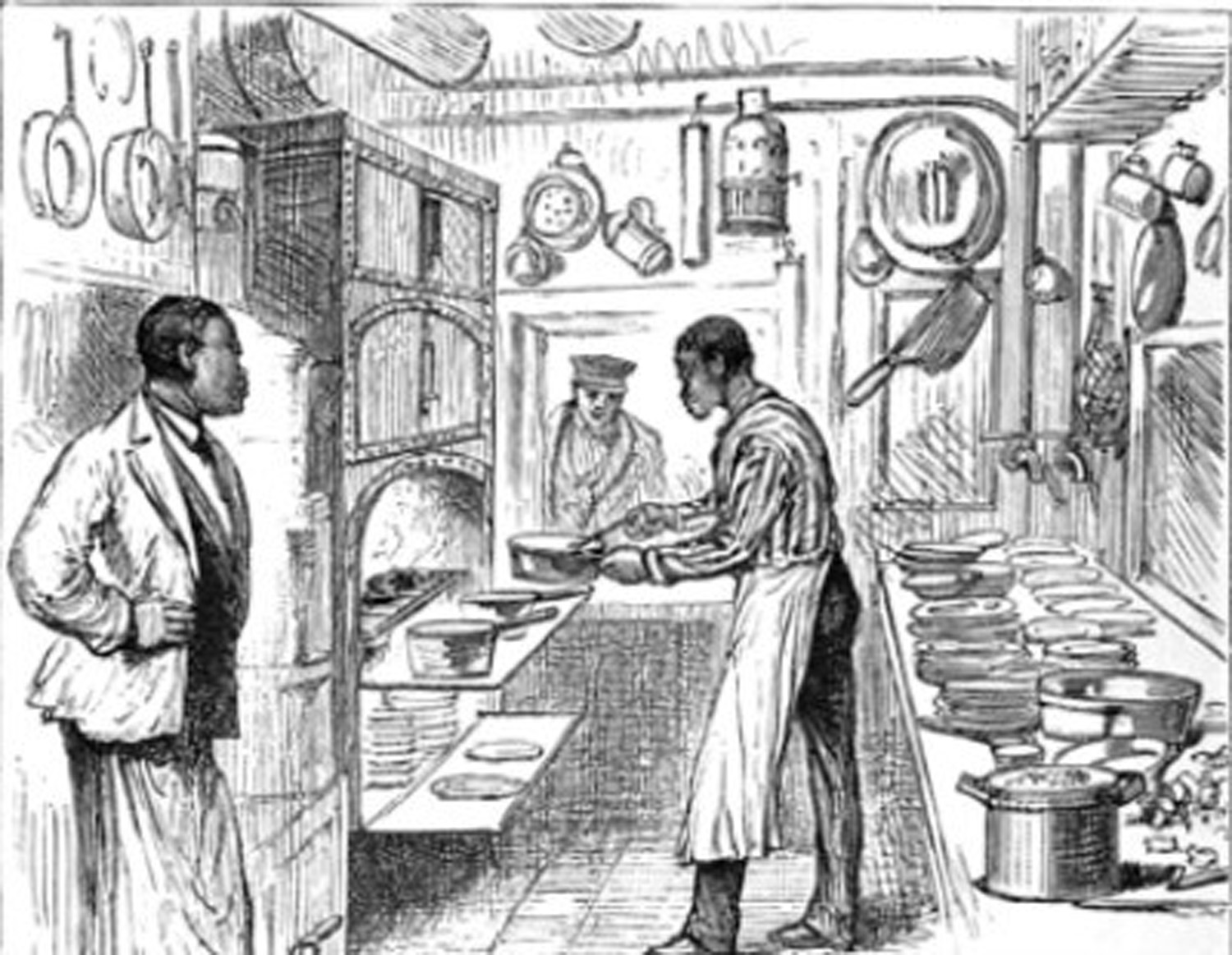

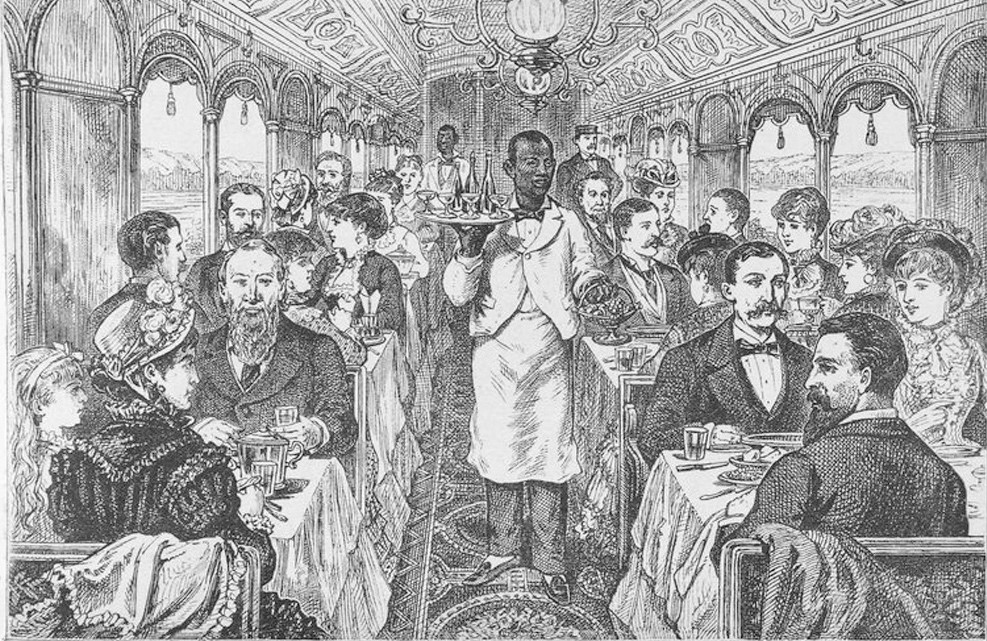

The kitchen of a pullman Car

A

After the group got in, a big old fellow made his appearance. He told them that they could come so far on one table and no further because they were not appropriately dressed. One of the fellows showed him an old revolver, and the big man got out of their way. The men ate all they wanted, then retired to look for a place to sleep. David had fully decided to report that gentleman in charge of the Retreat to the governor of the state. All the men found quarters for the night in a covered portion of the train depot.

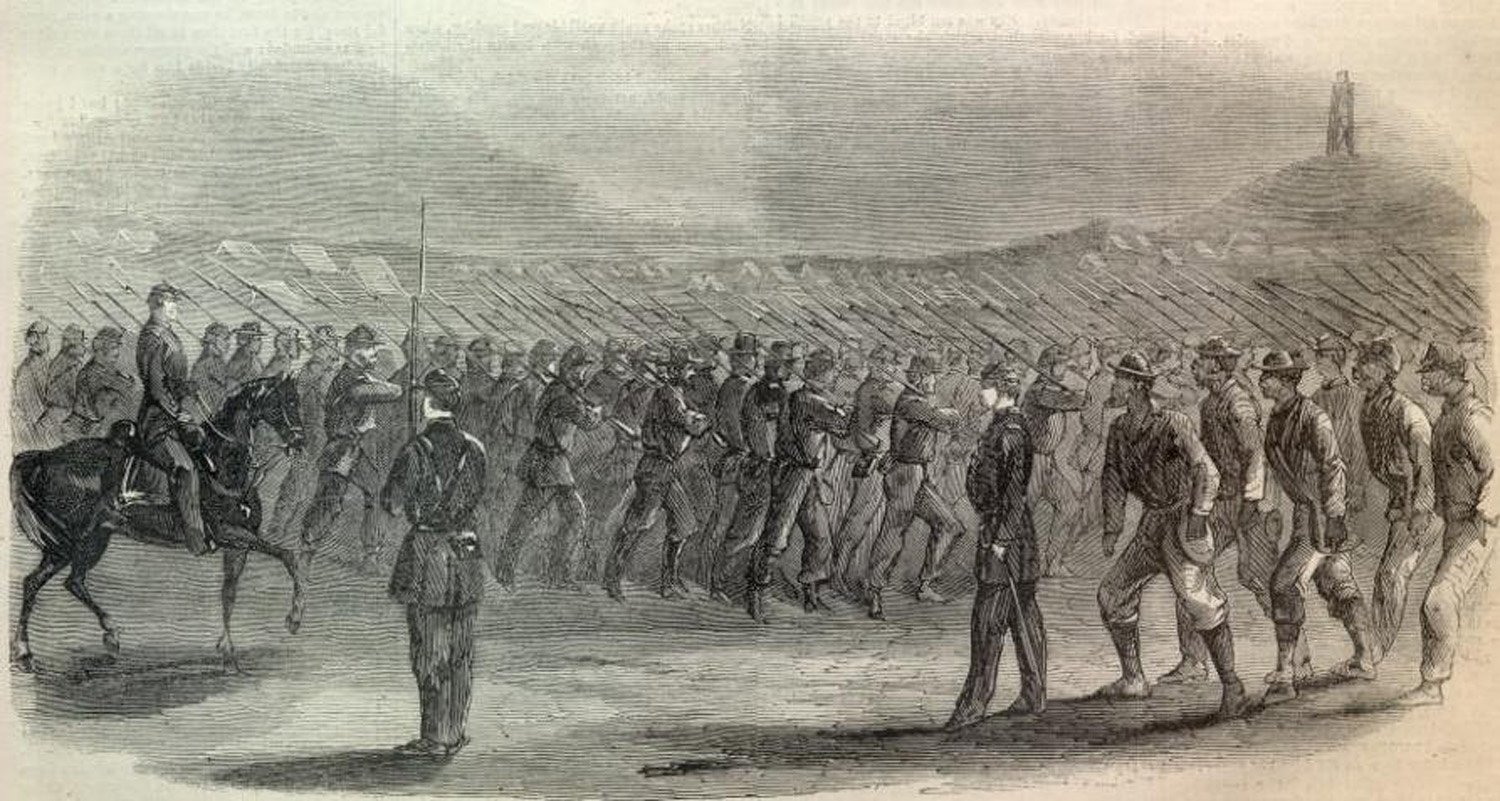

Just at daybreak, as David awoke, he heard commands, “Fall in.” The militia had arrived, which had been expected the evening before. He wondered what the mess hall was going to feed them after David’s men ate their meal. As they marched off, you could hear the officers calling, “Left, left, left.” David said in a low voice to the other men, “They’ll find out.”

Union infantrymen

The men found water behind the depot, took a wash, and some men cut their hair. Soon after that, a messenger arrived, inviting them back to the Retreat for breakfast. It seems that the cook made an early meal for the militia, but they had left before it was ready to eat. The big old man apologized for his actions the night before. He said, “I was just a little off, boys.” He took out his jug that softened their hearts, and they forgave him his sins for his whiskey.

Having a drink

The Colonel joined the men and asked them how they were all doing. Someone in the back shouted to him, “It’s too hot and dry to talk much, sir.” The rest of the men were left in uncontrollable laughter. The Colonel offered to treat the men to a beer. And with great appreciation, all accepted.

A captain said to the Colonel, “There is only one man here left from my company.” David and the captain were seated at a table. He went over the list of his men, inquiring after everyone by name. David could only report to him either killed or wounded. There were only twelve left of the company after the battles. The tears rolled down both men’s cheeks. The Doctor returned with arrangements for the men, and they were placed in a hospital on Mulberry Street.

Harrisburg Pennsylvania 1855

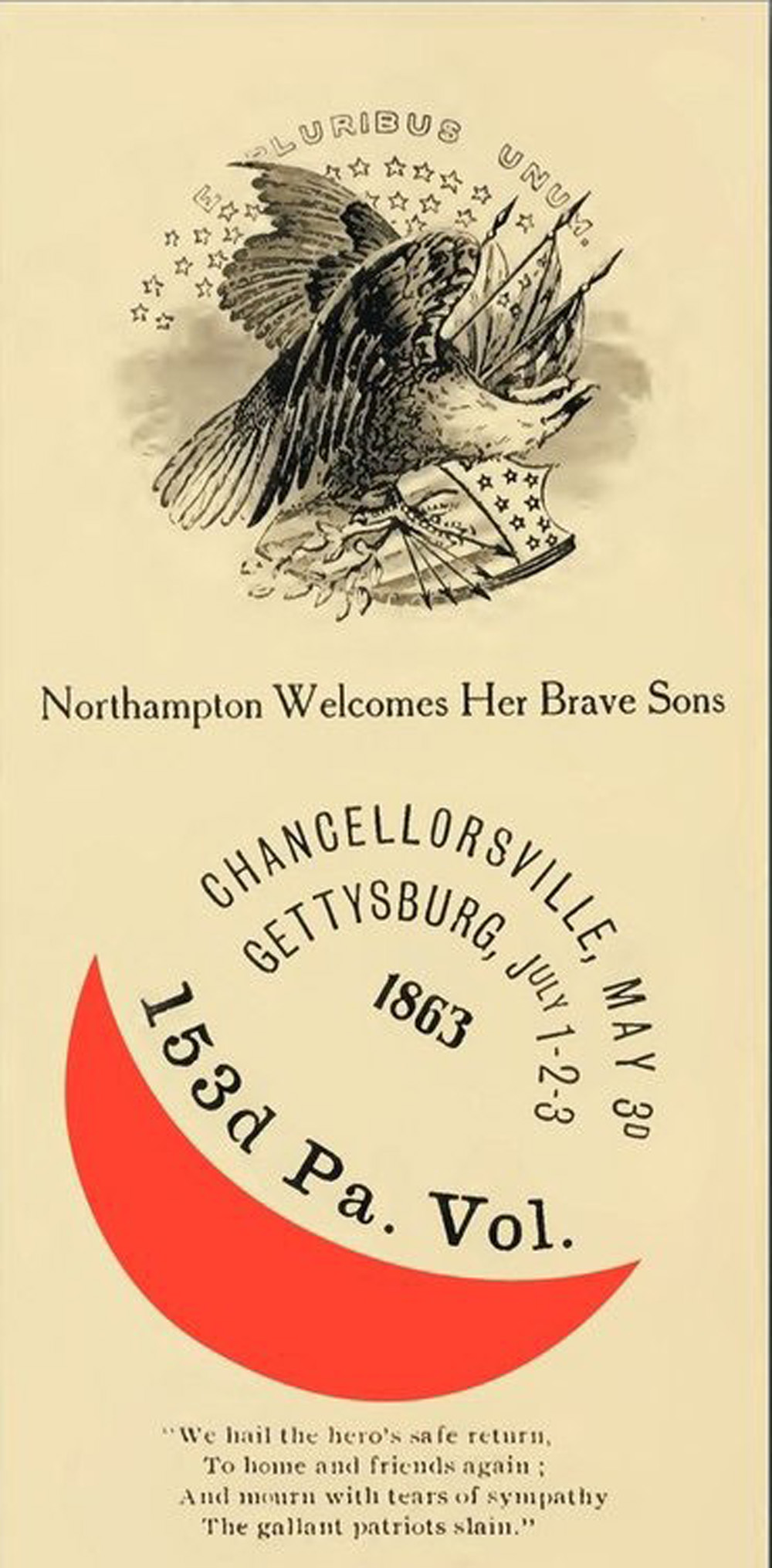

The regiment arrived in Harrisburg on the 17th. The citizens of the town treated the troops to everything to make them comfortable. Then the day came to return home. The first stop was at Reading. Here they were met by a committee from Easton, and they presented each man of the regiment with a badge of honor containing the corps mark, the battles they had been in, and the following poem.

Northampton Welcomes Her Brave Sons

We hail the hero’s safe return

To home and friends again

And mourn with tears of sympathy

The gallant patriots slain.

A grand welcome home

The boys were in fine spirits. The colors and their Brass Band was on the roof of the car. The next stop was Allentown Junction. David had informed Captain Stoul that he lived six miles up the valley from the Junction, and he could not walk it, and he had no money.

Dinning car on the train

The Captain started through the car to see if he could find twenty cents for David’s fare. He returned with the twenty cents all in pennies. David told him, “From the looks of the change, he must have got all there was.” He said, “I would not undertake to get twenty cents more out of that crowd.”

Sleeping car

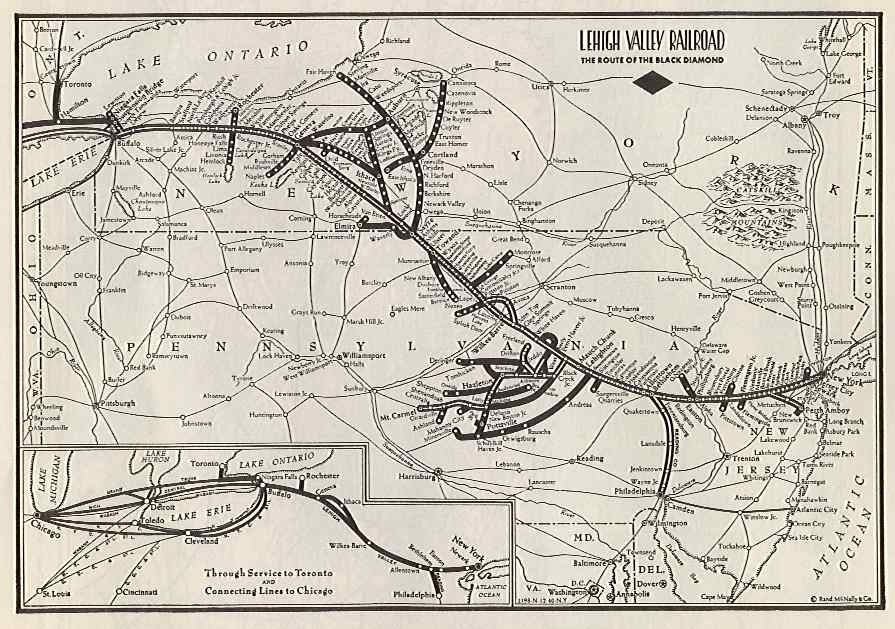

David and some of the men got off at the Junction, and by the time he got up to the Allentown Station, there were about twenty to go up the Lehigh Valley Railroad. They all expected to walk but David, for there were not twenty cents in that crowd, and he had it. But they were fortunate. An older man, his name was Lauhach, learned of their misfortune and bought tickets for all of the soldiers. David had been traveling two months without any money in his pocket, and he did not feel safe with twenty cents in the crowd I was in. The train came along, and they were soon at their destination.

Lehigh Valley Railroad

A coal train was passing at the time they arrived. Being between the station and the passenger train, and David not wanting to wait, he jumped out on the car’s platform. To his amazement, on the platform of the depot stood his mother and Rachel. They were expecting an uncle of his from New York City. In so little time, the living hell of war had changed David so much they did not recognize him. They could no longer see the vibrant youth that had jumped on the back of Henry the mule to ride off and enlist.

Civil War train station

The conductor was helping David off the train, and his medical tag on his back with his name was turned toward them. A young girl’s love spotted him, and Rachel was the first to call out his name. That was all it took, for the joy to see him and the pain of seeing him, to overcome each of them into tears. No words can describe how glad they were to see each other. It was hard for any of them to speak. When their uncle got off the train, he offered to drive the wagon home. They never said a word about David running away and going into the army.

The ride home in a wagon

On the ride home from the station, David and Rachel sat in the back of the wagon. David lay back on the straw to rest while she brought him up to speed on what’s been happening back home while he was away. He was exhausted, but he worked hard, keeping awake enough to listen to the latest news. His mother constantly interrupted them in the front seat, telling David one more thing sweet Rachel had been doing while he was away.

In the years before the Civil War, the lives of American women were shaped by a set of ideals that historians call “The Cult of True Womanhood.” The household became a new kind of place, a private feminized domestic sphere, a “haven in a heartless world.” “True women” devoted their lives to creating a clean, comfortable, nurturing home for their husbands and children.

Cult of true womanhood

With the outbreak of war in 1861, women and men alike eagerly volunteered to fight for the cause. In the Northern states where Rachel and Ruth lived, women organized ladies’ aid societies to supply the Union troops with everything they needed. They baked, canned, and planted fruit and vegetable gardens to feed the soldiers. They sewed and laundered uniforms, knitted socks and gloves, mended blankets, and embroidered quilts and pillowcases. They organized door-to-door fundraising campaigns, county fairs, and performances of all kinds to raise money for medical supplies and other necessities.

Women planting gardens

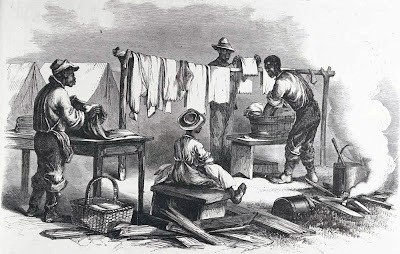

There were nearly 20,000 other women like Rachel that worked more directly for the Union war effort. Working-class white women and free and enslaved African American women worked as laundresses, cooks, and “matrons.” Some 3,000 middle-class white women worked as nurses. The war had given women a chance to control their own lives, earn their own money, and manage their own, finances. Some women were no longer complacently filling the roles they had filled before the war.

The activist Dorothea Dix, the Army nurse’s superintendent, called for responsible, maternal volunteers who would not distract the troops or behave in unseemly or unfeminine ways. Rachel was one of the many women, young and old, that responded with a “call to action.” Dix insisted that her nurses be “Past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.” No one ever stopped Rachel from serving, and her youth was overlooked.

Dorothea Dix,

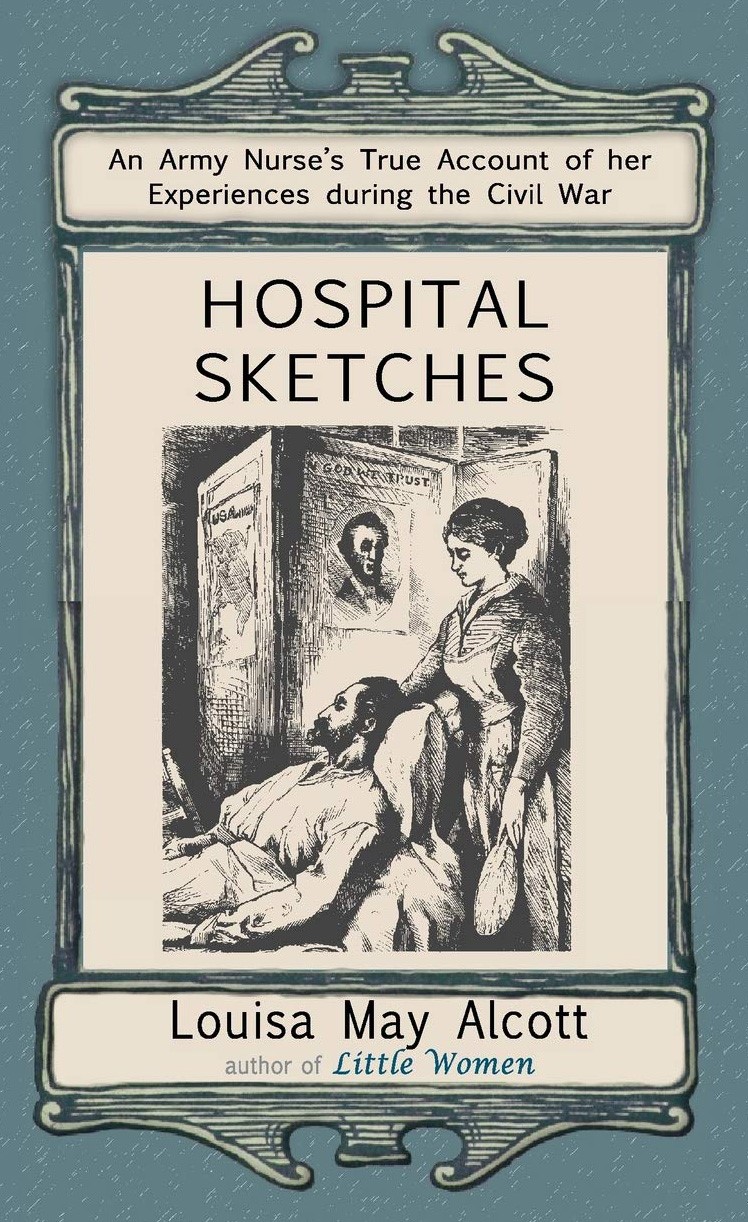

One of the most famous of these Union nurses that Rachel read about would later write the book Little Women. Louisa May Alcott. While serving as a nurse, Alcott wrote several letters to her family in Concord. At the urging of others, she prepared them for publication, slightly altering and fictionalizing them. The narrator of the stories was renamed Tribulation Periwinkle, but the sketches are virtually authentic to Alcott’s real experiences.

Louisa May Alcott – Little Women

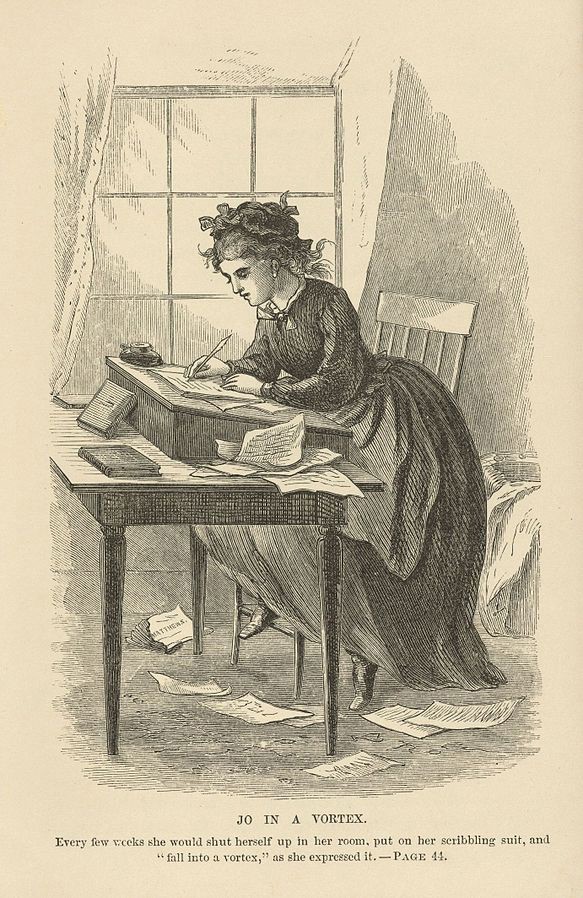

Published in 1863, Hospital Sketches was a compilation of four sketches based on letters Louisa May Alcott sent home during the six weeks she spent as a volunteer nurse for the Union army. Tribulation Periwinkle opens the story by complaining, “I want something to do.” She dismisses suggestions to write a book, teach, get married, or start acting. Then someone suggests that she go nurse the soldiers, so she does just that. While attending to the wounded from the Battle of Fredericksburg, she converses with the various wounded soldiers, including an Irishman and a Virginia blacksmith. Witnessing his death affects her deeply.

Hospital Sketches, Louisa M Alcott 1863

It was not known to Rachel and the public that Alcott herself did not care much for the writings. She dismissed the idea that they were “witty,” and she admitted, “I wanted money.” The pieces received great critical and widespread acclaim, making Alcott an overnight success.

John the blacksmith from a later edition of Hospital Sketches

Army nurses traveled from hospital to hospital, providing humane and efficient care for wounded, sick, and dying soldiers. They also acted as mothers and housekeepers, “havens in a heartless world” for the soldiers under their care.

Roles of women during the Civil War

The women of the south threw themselves into the war effort with the same zeal as Rachel and the other Northern counterparts. However, the Confederacy had less money and fewer resources than did the Union, so they did much of their work on their own or through local auxiliaries and relief societies. They, too, cooked and sewed for their boys. They provided uniforms, blankets, sandbags, and other supplies for entire regiments. They wrote letters to soldiers and worked as untrained nurses in makeshift hospitals. They even cared for wounded soldiers in their homes.

Women of the North and South

There are three ingredients required to make gunpowder: saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur. Desperate for saltpetre, the Confederacy sent out agents around the South to collect deposits of “Night Soil.” John Harrelson, an agent in Selma, Alabama of the Confederate Nitro and Mining Bureau, advertised the following in the local paper: “The ladies of Selma are respectfully requested to preserve the chamber lye collected about their premises for the purpose of making nitro. A barrel will be sent around daily to collect it.” This appeal went out to the southern women to save the contents of their chamber pots.

Making explosives

Many Southern women, especially wealthy ones, relied on slaves for everything and had never had to do much work. However, even they were forced by wartime necessities to expand their definitions of “proper” female behavior.

Women in the South working for the war effort

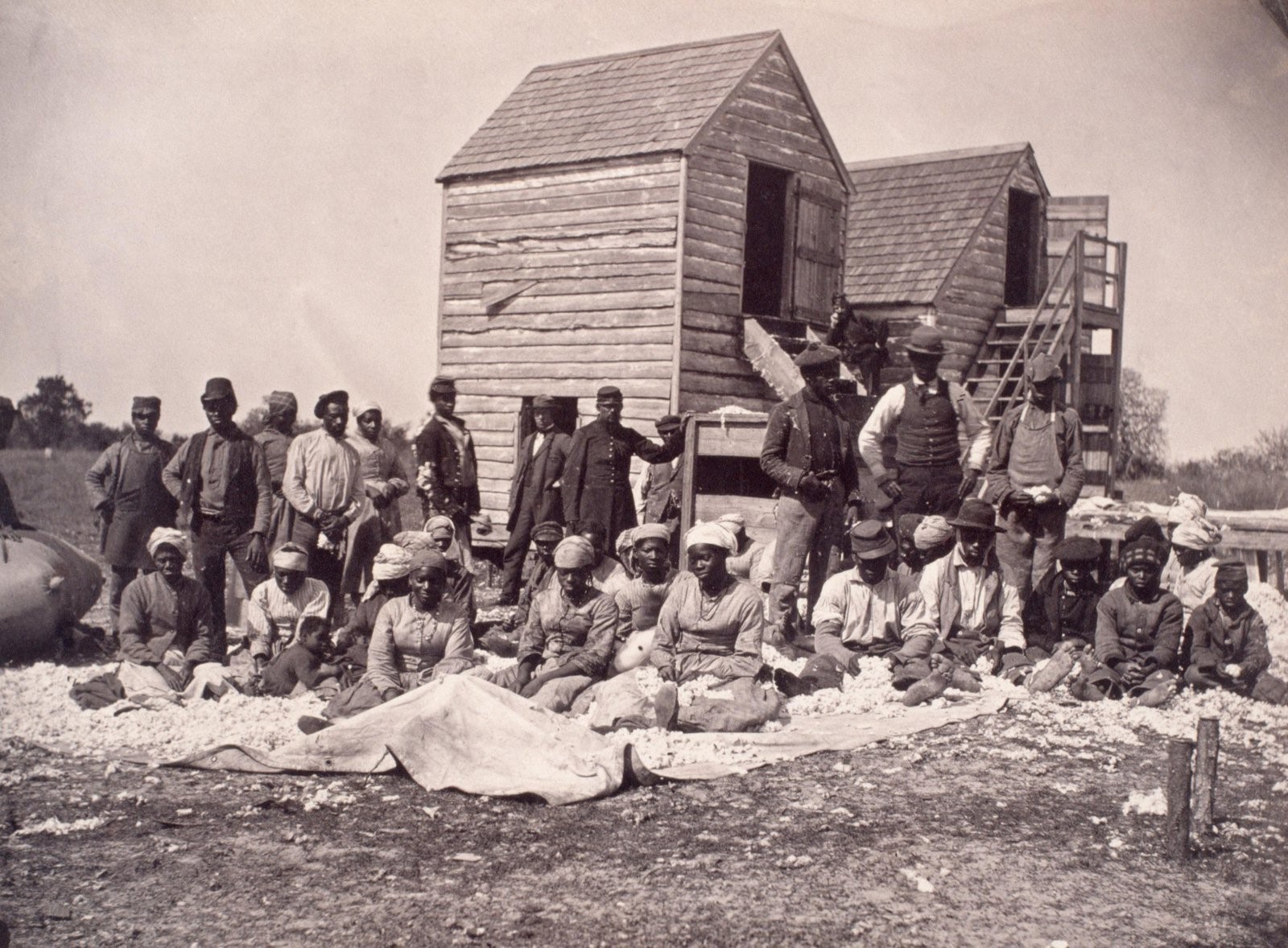

Slave women were, of course, not free to contribute to the Union cause. They never had the luxury of “True womanhood” to begin with. Being a woman never saved a single female slave from hard labor, beatings, assault, family separation, and death.” The Civil War promised freedom, but it also added to these women’s burden. In addition to their plantation and household labor, many slave women also had to do the work of their husbands and partners.

Work was never done for the slave women

The Confederate Army frequently impressed male slaves, and slaveowners fleeing from Union troops often took their valuable male slaves, but not women and children with them. Working-class white women had a similar experience. While their husbands, fathers, and brothers fought in the Army, they were left to provide for their families on their own.

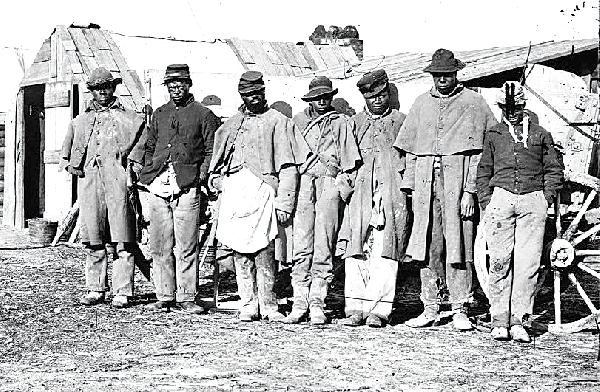

Black Confederate soldiers

Rachel told David that Ruth and one of his cousins got married just before the Battle of Chancellorsville. He was a year younger than Ruth but 6 inches taller and 50 pounds heavier. Rachel could still see in her mind him picking up her sister and sweeping her off her feet in his huge arms. Rachel told David that the two of them had been in love from an early age, but everyone already knew that, including David. His family all thought they were going to get hitched someday. His family could also see that Rachel had her eye out for David, but he did not know it. If he did, he did not show it.

A Civil War wedding

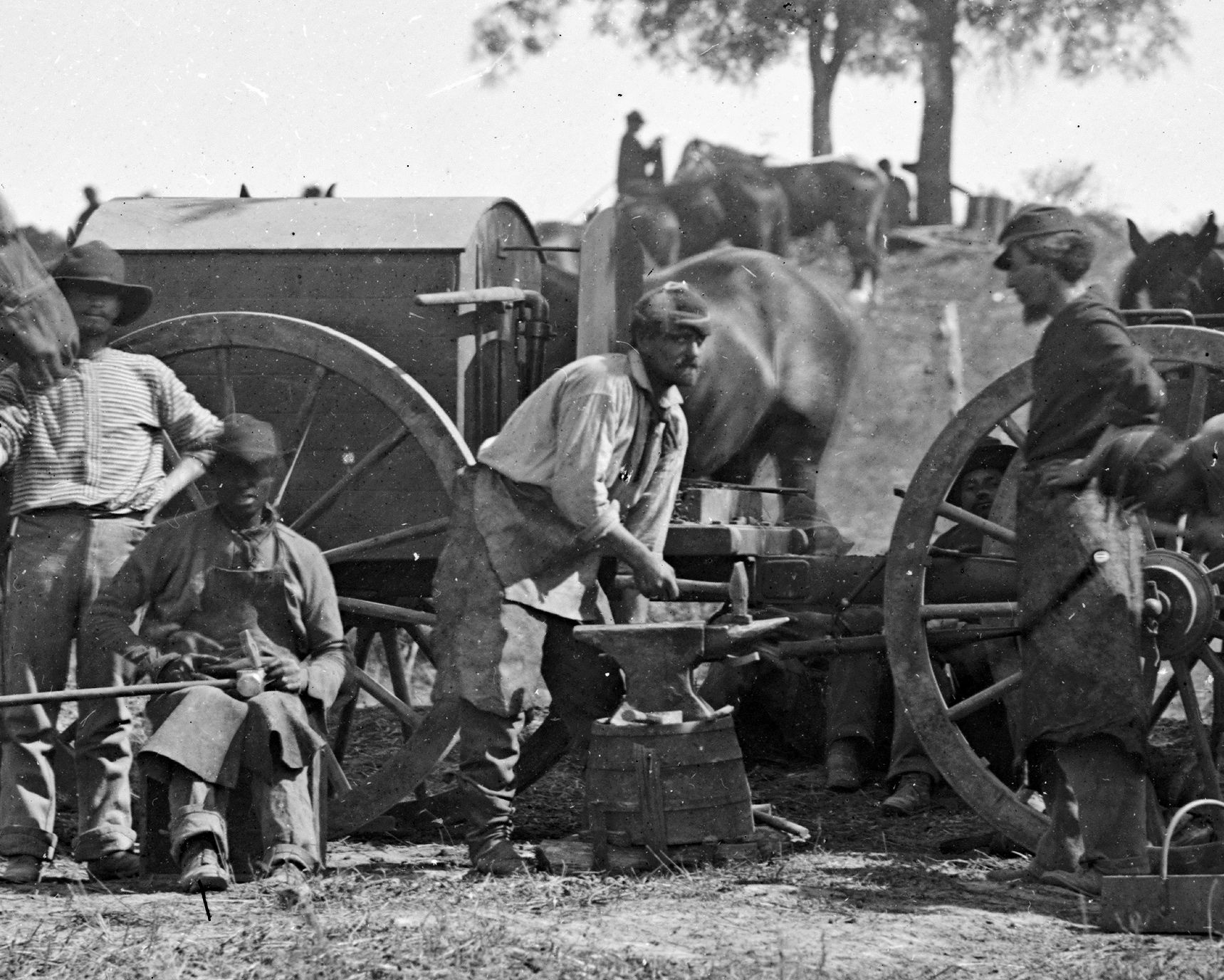

David could see the sadness of their separation in Rachel’s face when she told him that Ruth had gone along with her husband when he went on the march in the army. She traveled with many other men and women that were camp followers. They supported the soldiers as cooks, nurses, blacksmiths, Sutters and kept the army clean doing the laundry. Ruth had gone to war in order to share in the trials of her beloved husband. A thirst for adventure also stirred her.

Black slaves in Union camp – blacksmith

She went to war with her husband

David took a deep breath, and he got really silent when Rachel told him what happened shortly after they got married. The change in her voice triggered his sigh as she told him about Ruth losing her husband at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Women in the war