The march to Gettysburg

David writes a postscript in his diary.

June 12, 1863:

Today at about 2 o’clock pm, we commenced the famous march to Gettysburg. It was very dry for we had had no rain since May 9. The dust was from two to three inches deep, and one could see the heat waves curl up from the dry roads about twenty-five feet, having the appearance of the sun shining on a piece of hot iron. The wells and springs were about all dry, and the creeks very low. The clouds of dust would rise about one hundred feet above us, and I was informed that these clouds of dust could be seen for miles.

Timeline 1850 – 1858

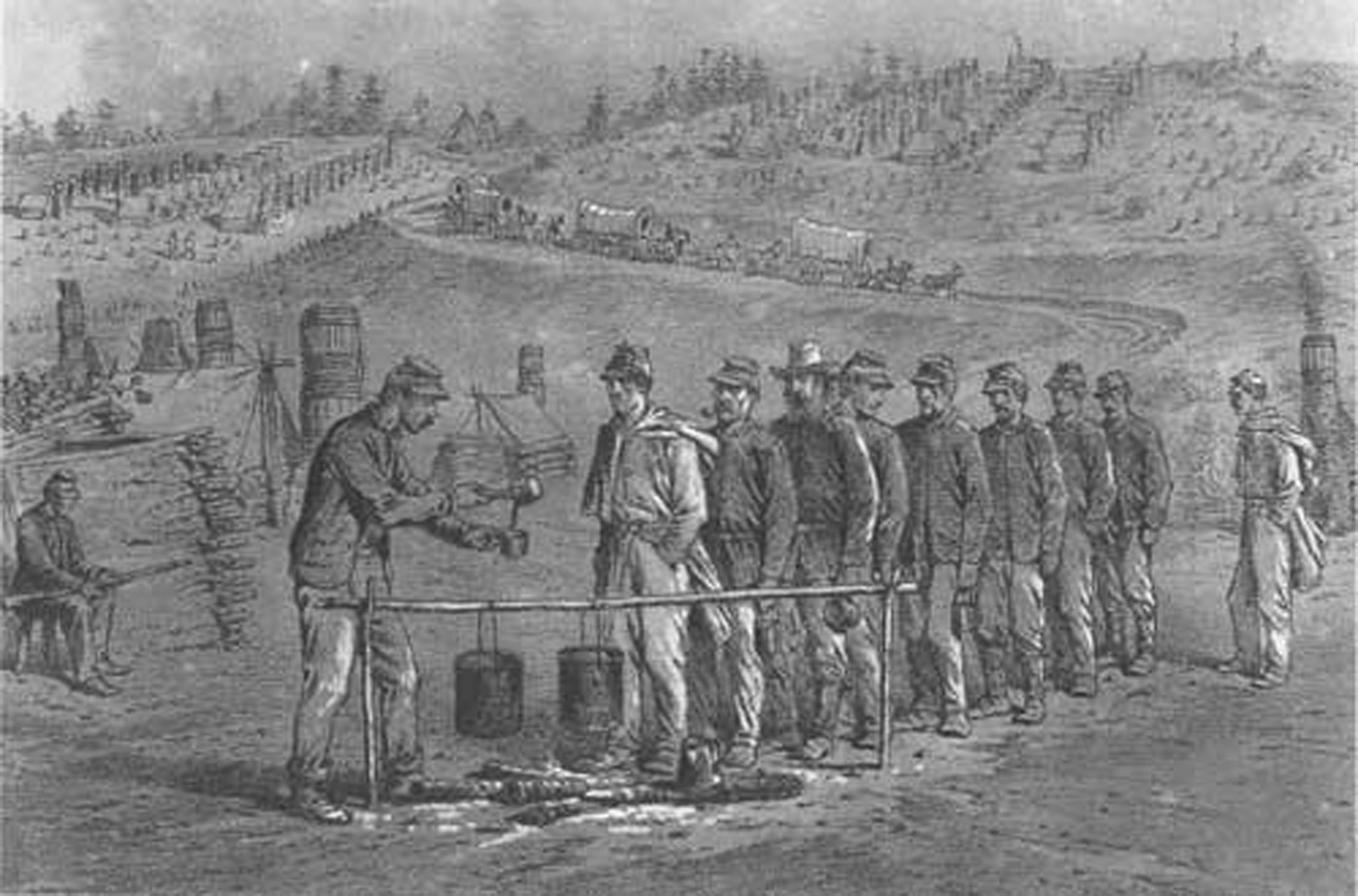

Union army camp

On arrival at the old camp, near Brooks Station, David found his regiment had started on the march towards Gettysburg. He followed it up, hitching a ride with the baggage train and rear guard. The wagon ride was very bumpy, so he used his haversack to soften the ride. David had some time to rest and make an entry into his diary.

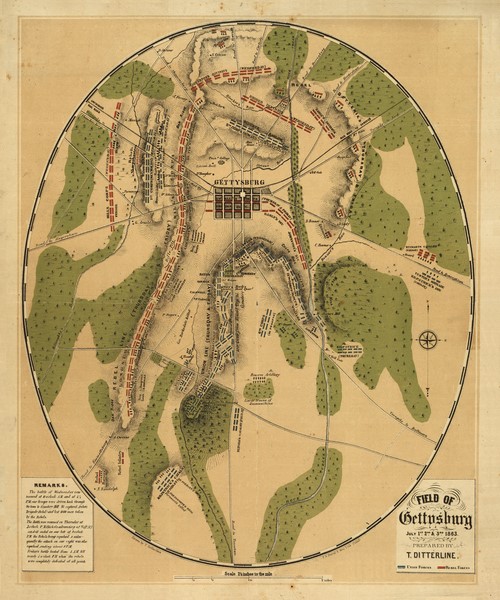

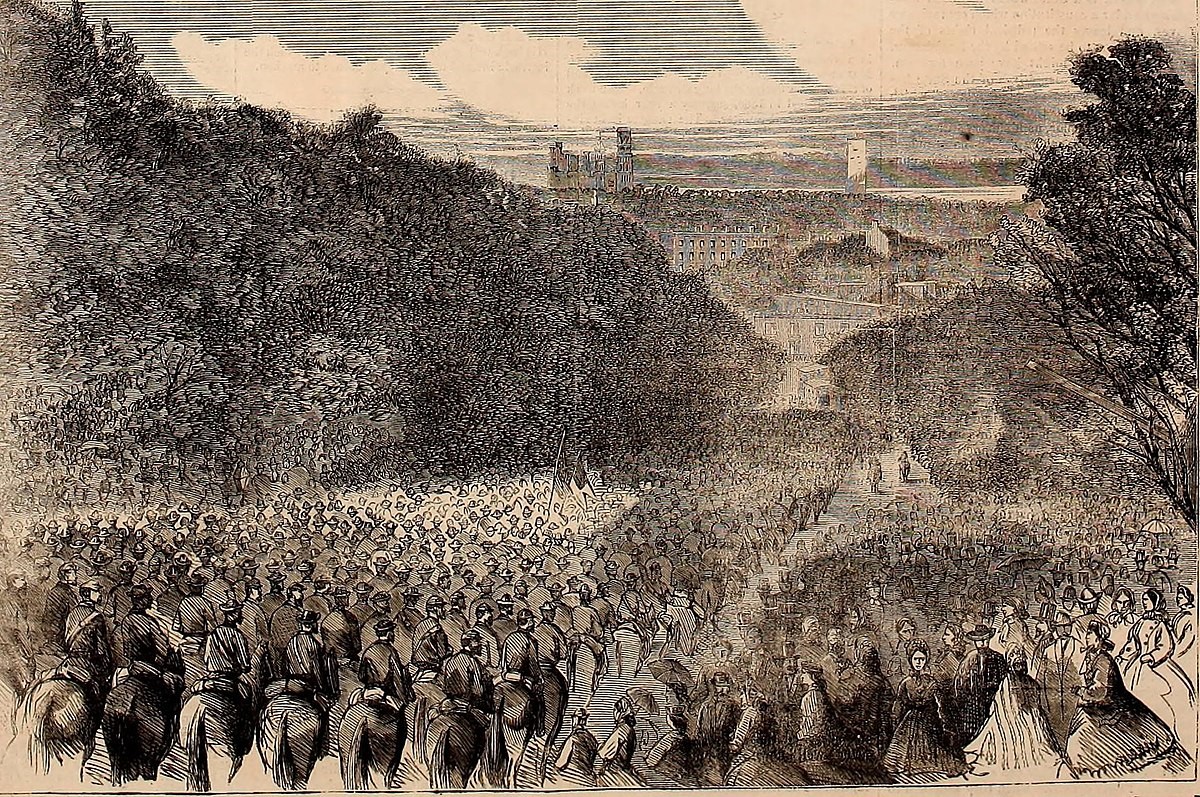

Field Of Gettysburg1863

Each time he opened the book and began to write, he could still smell the scent of home in the wrapping. He touched his face briefly with the cloth, then put it away as if it had great value.

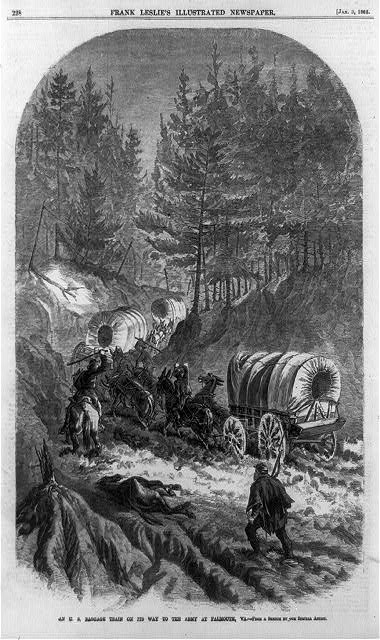

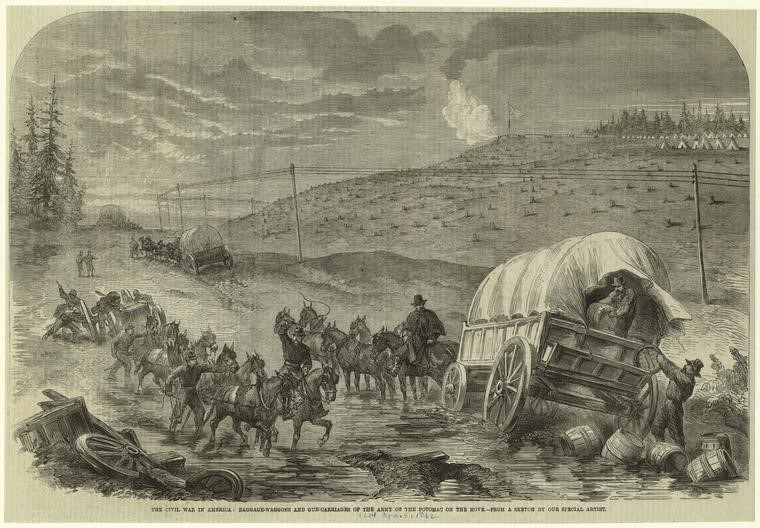

The supply train

June 12, 1863:

We went into camp about dark, and, oh, my ! Such sore feet as I had. When I pulled off my socks. . . .every toe had a blister, and on the big joint back of the big toe, the skin came off with the sock, as big as an old fashion copper cent. I did not stop to eat supper that night, but I lay down on my gum blanket with my overcoat for cover and was soon in the land of dreams.

The night watch

June 13, 1863

Reveille sounded at 3 am, and we left camp just at the break of day. There had been considerable speculation the day before as to where we were going. And as the road had been bearing toward the left, or south, the word was ‘left to Richmond;’ when the road turned toward the right this morning, saying was ‘right for Washington.

Marching, marching, marching

My feet were in a very bad condition. . . .after marching. . . .for eight or ten miles, two large blisters formed on the bottom of my feet about an inch wide and two inches long. I had to stop and open these blisters, and it was just like walking on coals of fire after this operation.

Civil War Zouave ambulance

It was not long before David was getting into the rear. He got so far behind the columns that he finally found himself in the group of the ambulance corps. Reaching out his arm, he caught hold of a wagon that pulled him along three or four miles, and David was quite relieved.

The rear of the Column

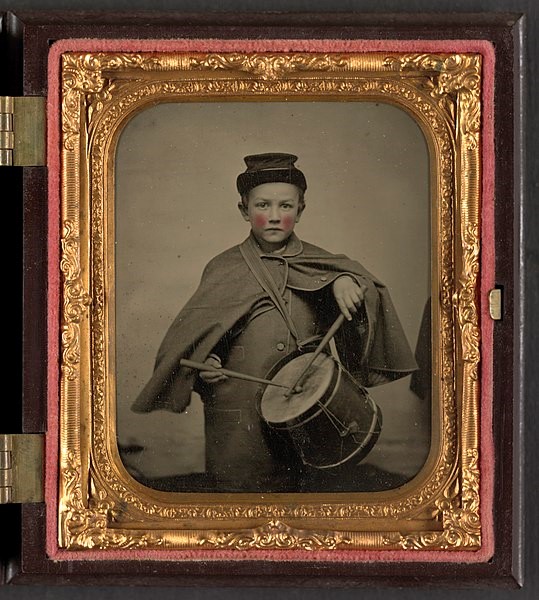

The wagons passed soldiers alongside the road who were overcome with the heat and exhaustion, too many to count. He saw several men that appeared to be lifeless, just lying there, and no one was paying them any attention. Under the dark shade of a towering oak lay the lifeless form of a drummer boy, apparently not more than 17 years of age. He had a tiny frame, yellow hair, and blue eyes. As David approached him, David stooped down and observed a bloody mark upon his forehead. It showed where the messenger of death had produced the wound that caused his death. His lips were closed, his eyes half-open, but his face displayed a bright smile of contentment. By his side lay his tenor drum, never to be tapped again.

Tintype of a Civil War drummer boy

Timeline 1877

June 14, 1863:

I fear the march from near Falmouth heights, in Virginia, to and beyond the town of Gettysburg, will be a long and toilsome one. The heat frequently is so intense that many of the rank and file dropped by the wayside. Some men to report, later on, others are still resting alongside the road in the camp of the “unknown.”

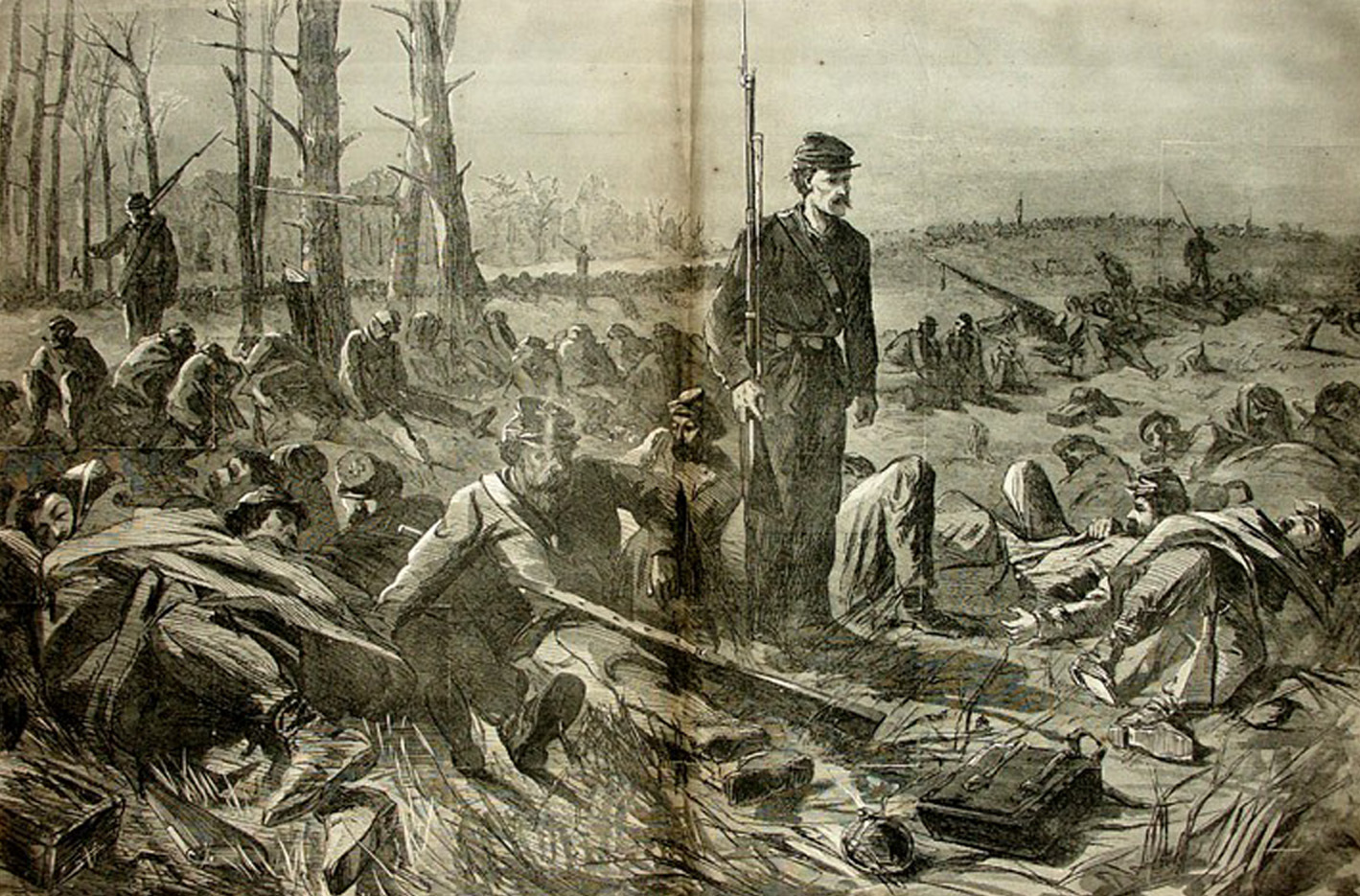

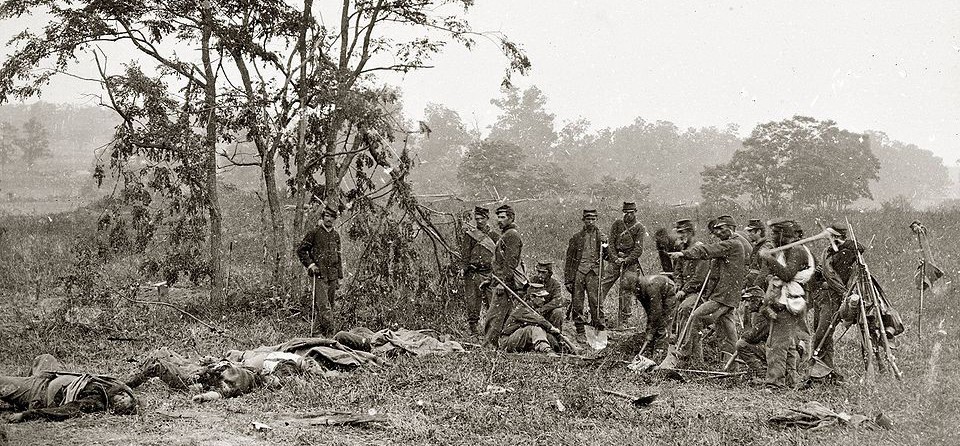

Collecting Union dead

Several months afterward, the bodies of these men were gathered for burial along with those who had fallen in battle.

The men got off the road to look for water, for everyone was thirsty. One of the men came to a pond in a field not far from the road. But when the soldiers tried to drink it, they found it to be the worst water they ever had tried. It was covered with a thick green scum with a lot of big long-legged flies skating over it. The pond was about two inches deep and filled with young frogs. And the water was thick and smelled so strong that David was sure that he could not drink it. But the men needed water, so they all filled their canteens out of this pond.

David put into the canteen about two teaspoonsful of coffee to flavor it. He came up to his company shortly after, and as he stepped into the ranks, the boys asked David, “Have you got any water”?

“Not a drop,” was his answer, yet he still had about half a canteen of the stuff he had gotten out of the pond. But water was water, and he could not give it away. David drank it all before they came to water again.

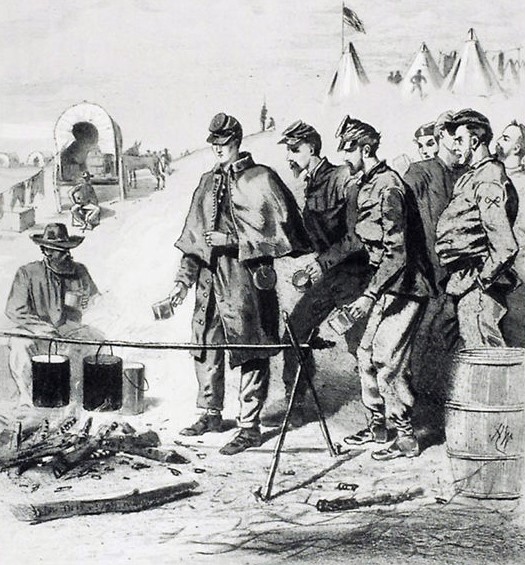

A coffee break

The troops stopped to cook a cup of coffee at about noon. Here was a little stream of water not over one foot and a half wide and about three or four inches deep, clean running water. It was pure, but as far as David could see up the stream, the boys were washing their feet in it. And by the time it got down to him, it was pretty well flavored. But this use of it made no difference to the men. They made coffee out of it, drank of it, and washed their feet in it. And as far as he could see down the stream, everybody was using it for the same purposes. It was the same old story, everybody’s feet needed washing, and as far as he could see up the creek, it was full of men, horses, and mules.

Drinking water from a stream

On the night the regiment reached Winchester, there seemed to be a mistake about going into camp. The Brigade would halt and then start, possibly making a mile and then halt again. This movement would be repeated over and over again. A laughable incident was noticed while the occurrences were taking place. A soldier by the name of Jemison was a cook for Captain Howell’s headquarters, and he had succeeded in getting quite a supply of fence boards to start his campfires with.

It was considerable load, and after the third order had been given “Forward,” he threw them down in disgust and swore he would carry them no longer.

Night marching

When “Halt” was sounded, he went back and got them again.

No sooner had “Forward” been ordered again when down he threw them. And for several minutes, the volume of epithets that poured forth would not have been suitable for the uplift of Christianity.

During a long “Halt,” the men took off their packs and set on them to rest. David took out one of his pencils and began to take notes in his diary:

No date:

My shoes have become literally worn out ; the bare skin being exposed. During the march of the first day we passed through grain fields. In one of them the grain had been cut and removed, and the ground was what the farmer calls a stubble field. I, with my exposed feet, ran ahead of the rest of the men, like as if the rebels were close at my heels. Figuratively speaking I saw stars in broad-day-light.

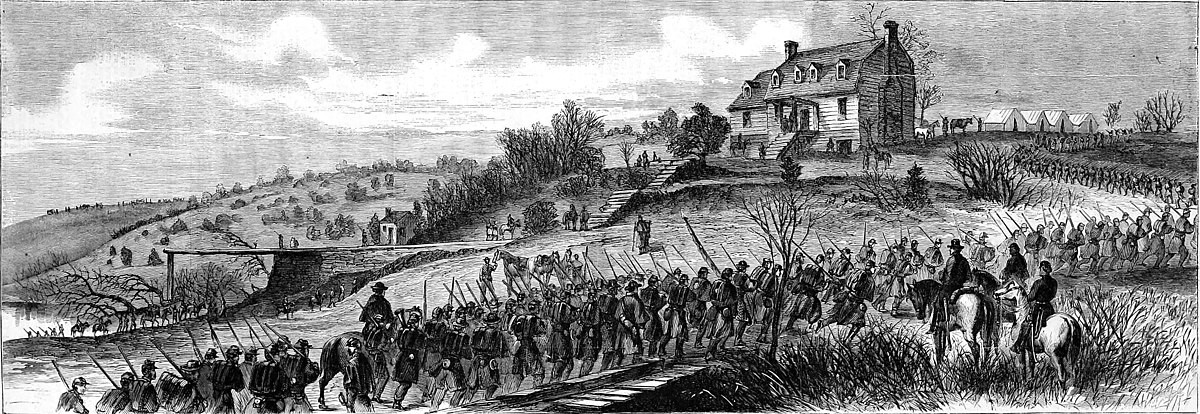

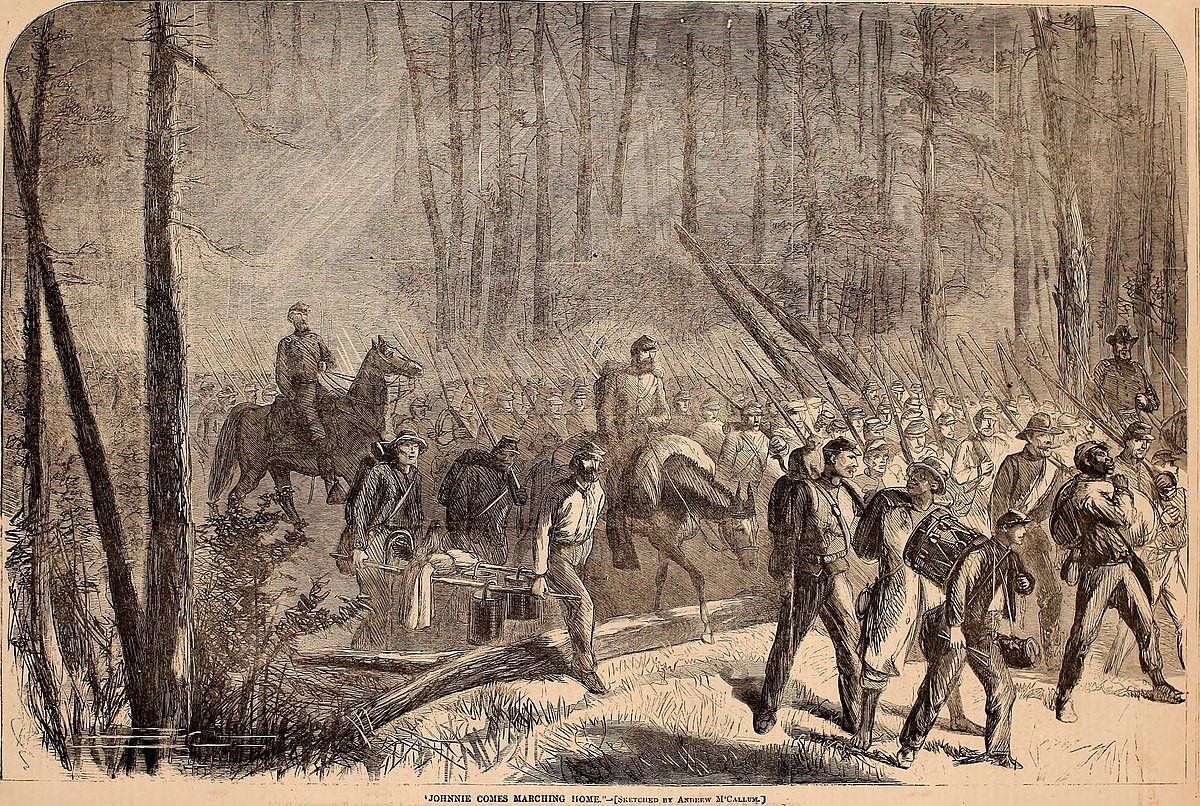

Union soldiers on the march

The order “Forward” came, and David put the book back in his haversack, but before he could fall in line, the order came again to “Halt.” Along with the other men, he sat down again and continued to write down his thoughts.

No date:

By the power appointed to me by God to watch over the interests of my family at home and to sustain the army in the field, both by marching with men forward, and by protecting those from the slanders of traitors, and the lying tongues of misnamed friends, I take the liberty of giving a truthful account of the doings of the one hundred and fifty-third regiment, Pennsylvania volunteers.

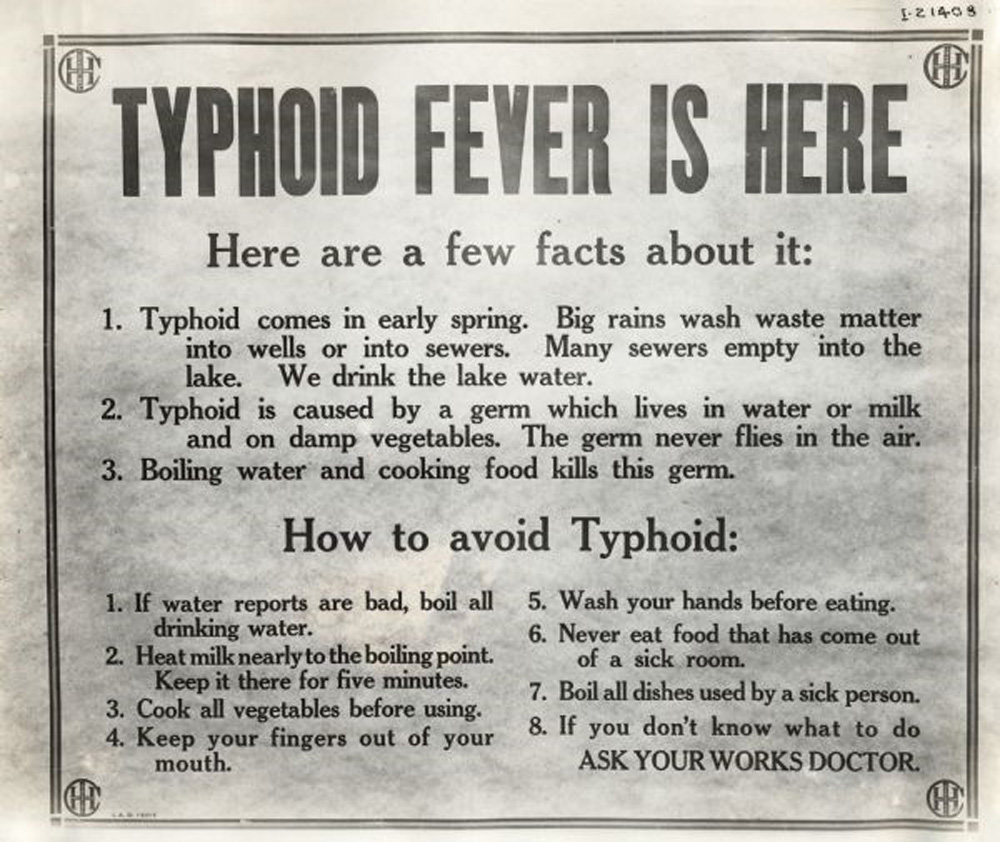

On the march to Gettysburg Comrade, King was attacked with typhoid fever, and with many other sick men, they were advised to go home. Though still weak from his illness King started for his home and, on the way in the darkness, was overtaken by a man on horseback. He was a farmer who happened to be a neighbor of David’s parents. On speaking to him, and to his great joy, he learned that this man was Charles Long. Mr. Long instantly dismounted and placed the soldier in the saddle and accompanied him to his home. The joy of the family was indescribable, and all sleep was suspended for the entire night.

Typhoid fever health announcement

Typhoid fever is an intestinal infection that is spread by ingesting food or water contaminated with the bacteria Salmonella Typhus. Such contamination was usually widespread in army camps and caused massive epidemics. During the Civil War, there were 75, 418 cases in the Union Army, and 27,058 (36%) of them died. Far more soldiers died of typhoid or dysentery than of battle wounds.

Union soldiers being laid to rest

Entry in David’s diary.

June 15, 1863:

I bought a pair of woolen socks from one of my comrades for fifty cents on credit, for we had no money. I do not remember now whether I ever paid for them, but I promised to do so, and that is good enough for these days. By the time I got my feet fixed up, the bugle called for us to get up and travel. I started with the regiment and kept up for some time, but I had to frequently stop to fix up my feet. By the operation on their bottoms and under these circumstances got away to the rear of my regiment into the wagon train.

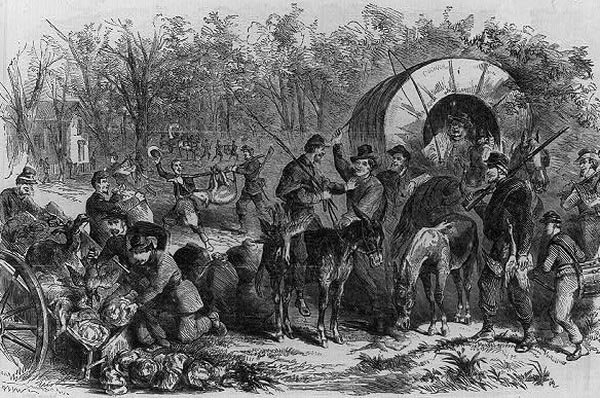

The supply wagon train

Over half of the men were barefooted, and many were lame and were sent to the rear. Others, of sterner stuff, hobbled along and managed to keep up, while gangs from every company went off in the surrounding countryside looking for food.

Looking for food

Many became ill from exposure and starvation and were left on the road. The ambulances were full, and the whole route was marked with a sick, lame, limping lot that straggled along.

Marching on

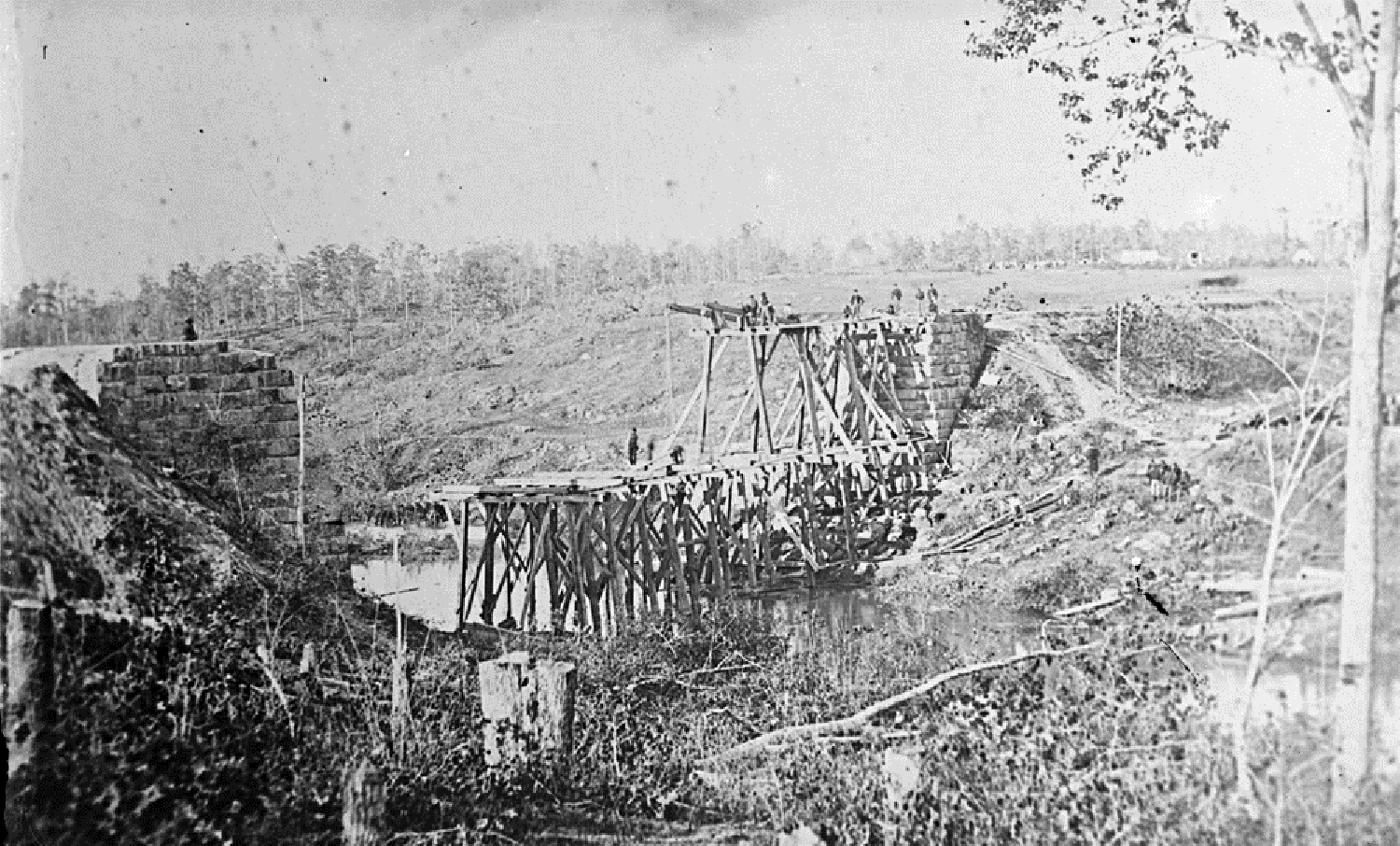

By degrees, David caught up with his regiment about a mile before it reached camp. The Company was on Cedar Run when he came up, and all the men gave out three loud cheers as they always did on his late arrivals.

Then the men sang, “for he’s a jolly good fellow” as they approached their destination.

Federal soldiers rebuilding the bridge over Cedar Run

The Company was just starting when a big fellow by the name of Benjamin Mann and another man dropped in the road with sunstroke. They both were carried out under a shade tree, and the doctor called. But before he made it there, the other man died. No one could identify him, and he carried no papers that would tell them who he was. He was left right where he fell beside the road as another unknown soldier. Benjamin was with the regiment again for a few days, but later, he was killed at Gettysburg.

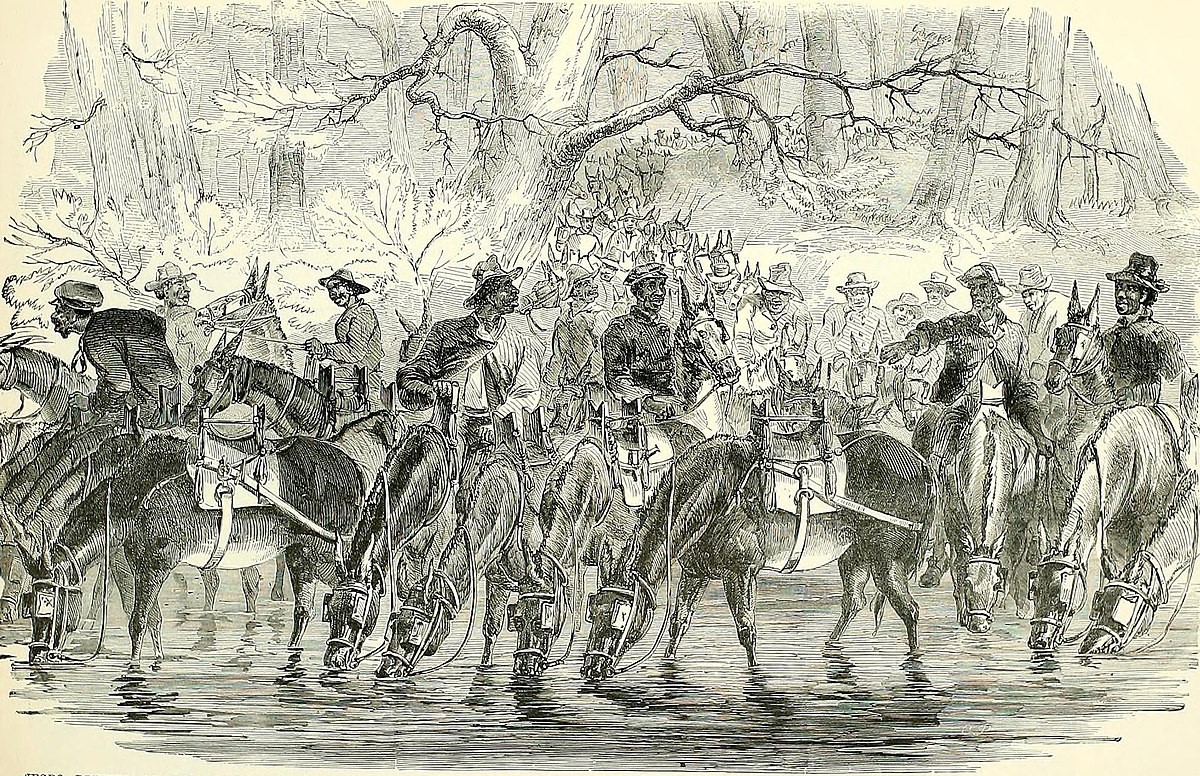

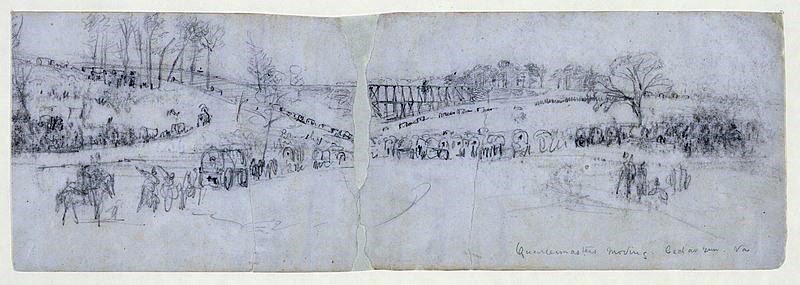

Battle of Cedar Run – Quartermasters moving

The columns made thirty miles this day. It was on a wager with the 2d Brigade. Brigadier von Gilsa had put up three hundred dollars that the 1st Brigade could out-march the 2d. An incident happened on the march. The company came to a well, which had an old-fashioned oaken bucket and windlass. The crowd around the well was about two rods deep, and every man was “as dry as harvest hands.”

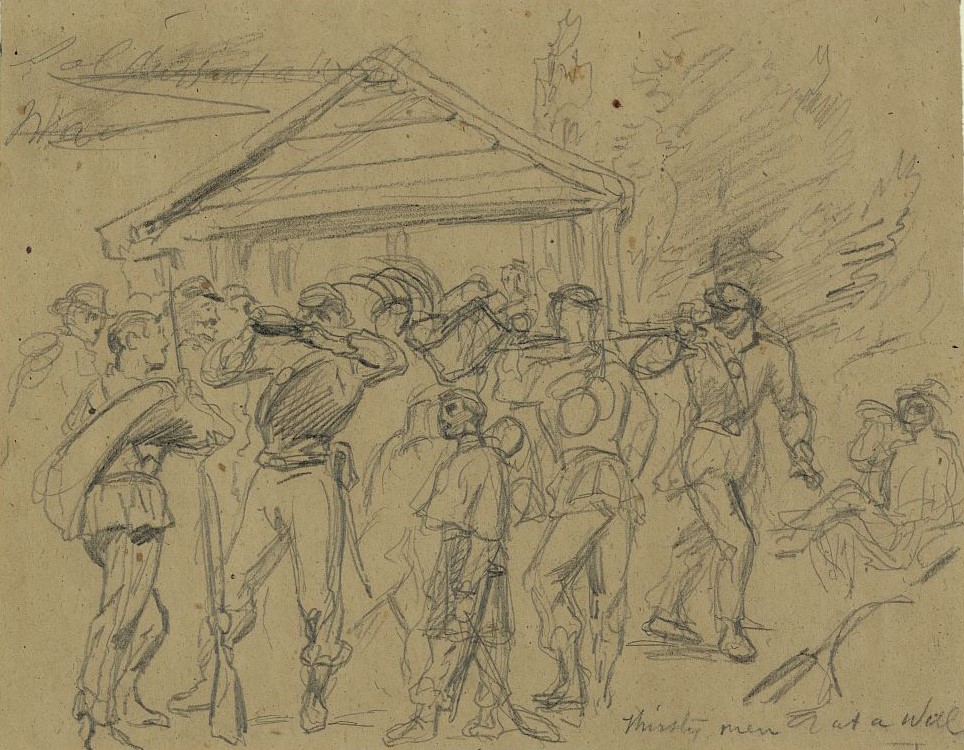

Civil War water well

David worked his way up through the group and came behind a big fellow named Wolf, who belonged to Company D. He looked over his shoulder and said to him. “Hang on to me, Davie.”

With his tin cup in hand, he got hold of Wolf and held on to his waist with both arms. Wolf got hold of the bucket as soon as he could reach it. Three men on the other side of the well got hold of it the same time Wolf did. He got the bucket, and two men on the other side came very near falling in the well.

David’s tin cup was now full of dust, but it was the first one in the bucket. Now to get the tin out of the bucket full of water was quite another thing. All that could crowd their tins on top, and by the time he got his out, it was only a half cupful of dust and water. The bucket had fallen to the bottom of the well, so the boys went marching on. David and Wolf did not get a drop of water for their trouble.

David and Wolf did not get a drop of water for their trouble

The 1st Brigade was in camp about one hour before the 2d arrived. General Gilsa made a beautiful little speech to the men congratulating them on their exceptional marching qualities and thanking them for making the distance in a short time and beating the 2d Brigade. The pencil was put to paper as David wrote in his diary.

June 15, 1863:

After supper (coffee and hard-tack)—I went down about one hundred yards through a nice meadow to take a bath. I thought I would return to camp in my bare feet, but I could not walk, so I got down on my hands and crawled back to camp…

Soldiers taking a bath

June 16, 1863:

Reveille sounded at about 5 o’clock. After breakfast of coffee and hard-tack, a runner came through camp that this was Sunday and that it would conflict with General Howard’s Religious principles to march on Sunday. I, for one, was wishing that the general’s religious spell would last all day, but by ten o’clock a. M. The bugle sounded calling us to get ready to march.

Sounding Reveille

While the company was packing, Chunky and the band gave them lots of music. But music had minimal effect on the troops, for they were too near dead from fatigue.

An anonymous voice in the crowd yelled out, “If I had been offered ten thousand dollars this morning to march ten miles, I would have refused it.”

The company band

After the music came the old familiar command, “Fall in.” But the boys did not get up and fall in. Instead, they answered the call-in language that best not be repeated.

“Fall in”

The officers could not get the men started. Finally, the old Brigadier General von Gilsa gave the command in his strong vernacular (full of expletives), which had the desired effect of getting the army in motion. On account of the condition of the men, it was almost impossible to move them. The entire company rested at the end of the first half-mile, the next rest coming at the end of a mile. Now able to make a few miles, they began to get warmed up, then there were no more stops until they came to Broad Run.

The Broad Run

Entry in David’s diary.

No Date:

Being behind when the rest came into camp, I told the doctor that I could not go any further. Dr. Stout told me that when the column started, I should drop out and he would give me a pass for the ambulance and that he knew that I was. . . .not able to keep in ranks.

It was not long after the men left camp, the drinking commenced, and they drank all the water they could find along the road. It made no difference to them whether it was good or clean, only so it was wet. The weather was hot and drinking so much water caused many poor fellows to fall by the wayside. David came along where they were burying men who had died from the effects of drinking too much water.

No date:

I did not know how soon our time would come to go hence. We got to Centreville Somewhere between 8 and 9 am, and I was not long finding a spring, with a crowd about three rods thick. I crowded into the spring. By lying down, I could reach the water, could get about one-third of a tin full at each dip, and got my canteen full of mud and water.

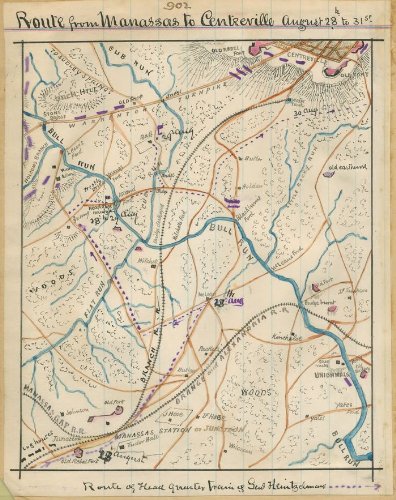

The route to Centerville

David got out of the crowd and came up to the village. There he saw another well with a wooden pump in it, and he was the first and only man to find it. There David met a boy about ten years of age at the well. He said, “Let me fill your canteen.”

David told him, “Let me see some of the water first because my canteen is full of spring water. Such excellent water I have not seen for many a day”. David told him he might fill his canteen, and he went to work at once.

The boy commenced to pour out the contents—mud, water, coffee grounds, lemon peels, and the like. It was truly laughable to see the look of astonishment on the lad’s face as he saw the contents of the canteen. David left with his tin cup, coffee kettle, canteen, and himself included full of that good water, and he left the boy with a soldier’s blessing.

In the street, David met Doctor Stout and asked him if he would like a drink of well water. As he emptied the tin cup, he asked, “Where did you get this water?”

David pointed to the well, and he went and filled his canteen also. Some of the other men found a meadow near a beautiful spring, so they moved their camp closer to the water.

Thirsty men

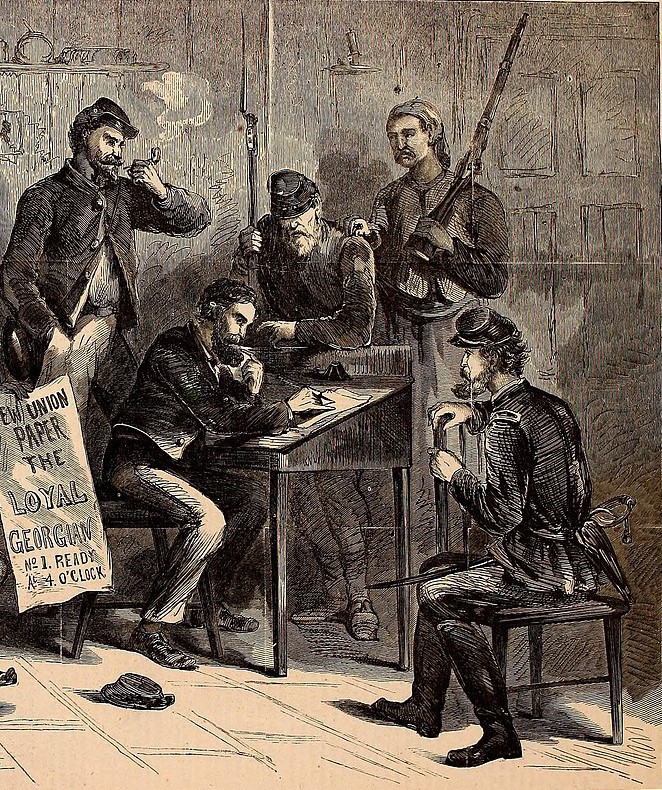

It was on this evening that Colonel Glanz arrived, returning from Richmond Libby prison. David knew personally what kind of treatment the man had been exposed to.

Richmond Libby prison

The men all turned out in their stocking feet to greet the Colonel. He made a speech to his comrades and dropped a few silent tears. The old man had changed since they all had seen him last. He was quite overweight when he was with them before, but he was just about as thin as a rail when he got back. After joining them, he went with the regiment a few days but did not take command, claiming he was not well.

Writing letters home

The men went back to their tents and spent the evening writing letters home. David helped several comrades keep in touch with their families by helping the men that could not read-write letters. After he completed this service, David opened his haversack and took out the scarf package. He made himself comfortable and wrote in his diary.

David helped several comrades keep in touch

June 17, 1863:

On the 17th, as I arose, a comrade of mine by the name of Henry Zearfass was still sleeping. I aroused him and told him to get his breakfast as there was a hard day’s march before us. He told me his commissary supplies had run out. I took my cap and went around among the boys and soon had it full of coffee, sugar and hard-tack which filled his haversack for him. He was a nice young fellow, he had been wounded in the face and he had no cheek. He would starve before he would beg. After breakfast, while we were packing up, my tent-mate had a nice piece of bacon, and he said to me, “David, I am going to throw this away. I can’t eat pork anyhow.” I told him to give it to me I would carry it; for I thought the gentleman would eat pork about noon. And I was right.

Camp in the evening

The company left Centreville about four a. m. They had made five or six miles when a halt was made, bringing the troops to a house. There were three men at the home. One had a bandage around his head. One had his arm in a sling. The other was lame. The boys accused them of being Rebels, and they denied it. David and some of the other men were leaning against the garden fence. In the garden, there was a small bed of onions. With a little bit of help, the fence fell over, and there was a mad dash. All he got was two onions as the bugle sounded for them to fall in.

>>>Click here <<<

Next: The march to Gettysburg – picture book – 2