From wilderness……….

….to wasteland

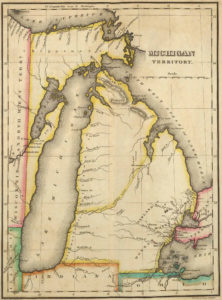

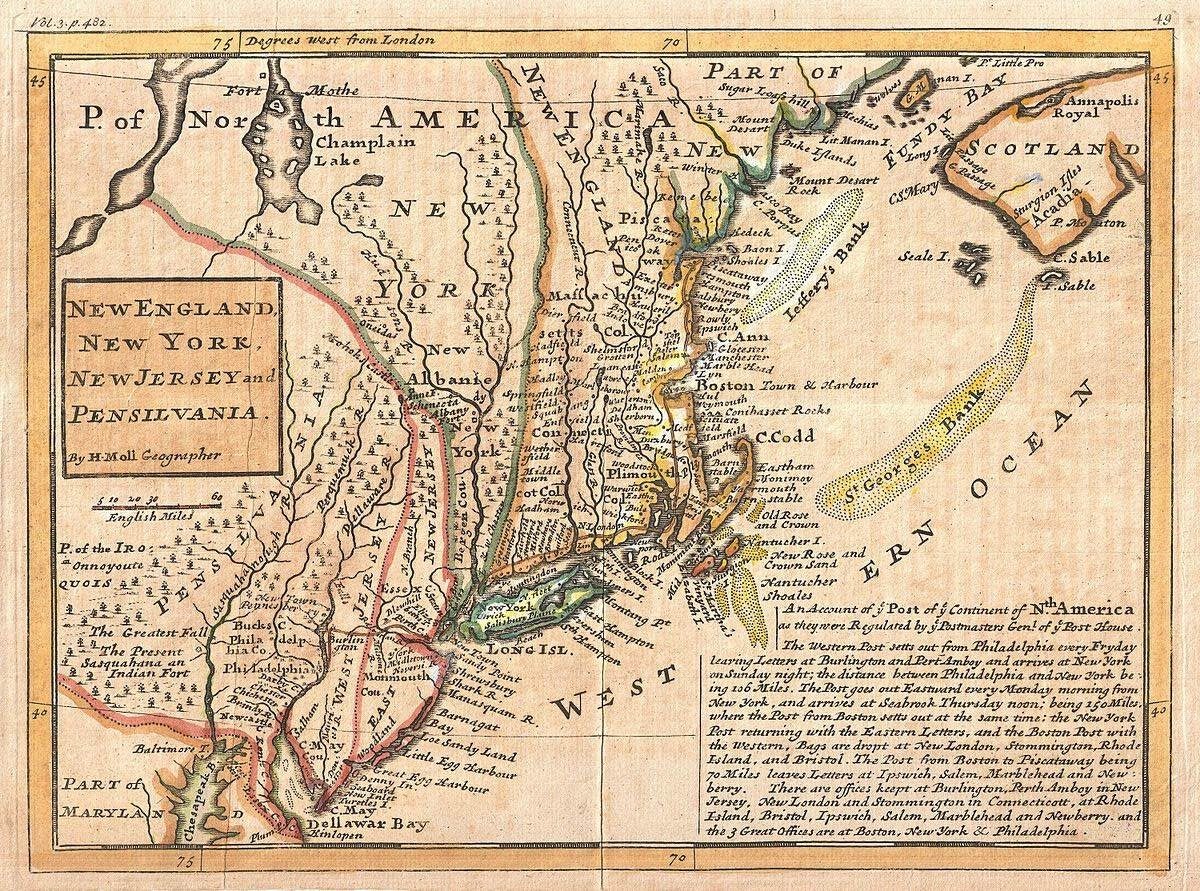

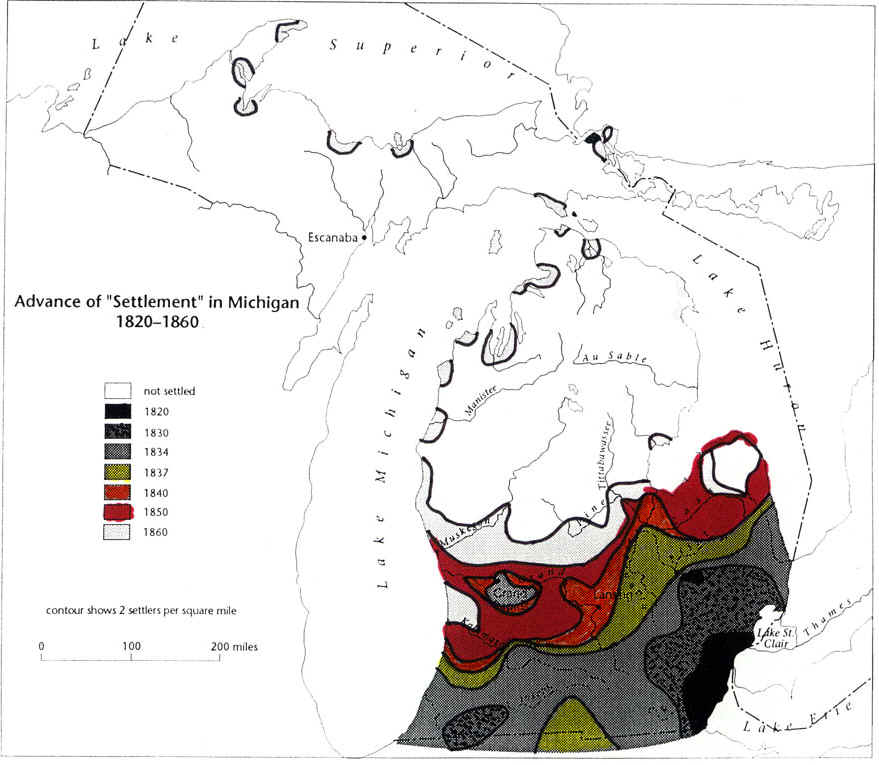

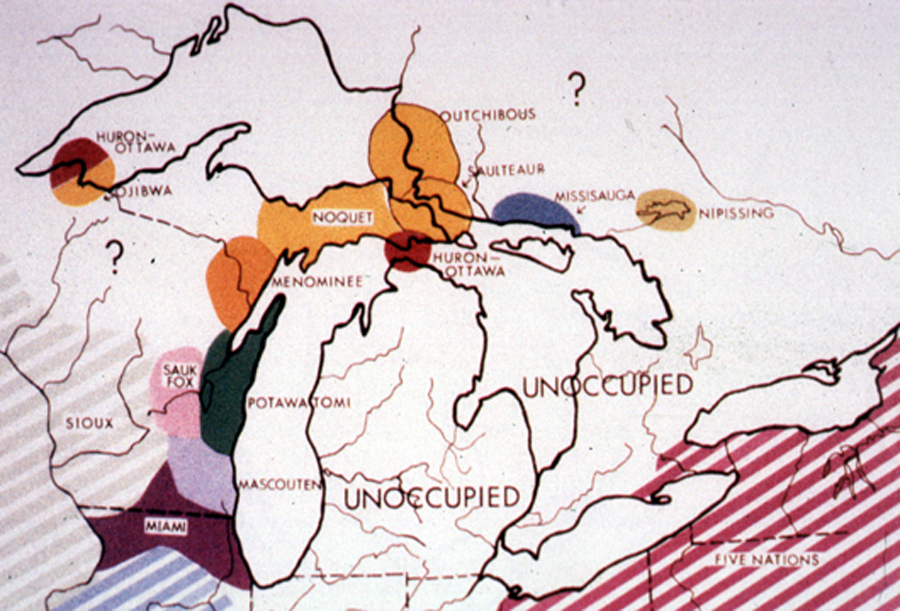

Michigan: 1822 Territorial Map

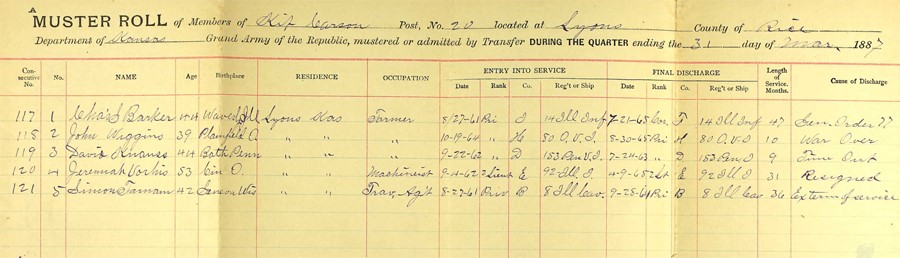

David Knauss muster roll

Shortly after being mustered out of the army, David went west to Illinois. For a time, he boarded with the Clark family in the Town of Charleston, former home of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s famous Log Cabin was just outside of Charleston. Mrs. Clark was the daughter of Dennis Hanks, whom David knew very well from the war. Dennis had written to him about finding work.

Lincoln’s boyhood home

David got a job on the railroad running between Illinois and Michigan. While traveling through the states, he saw an opportunity in the open land cleared by the loggers. Good farmland was there; all you had to do was remove the tree stumps.

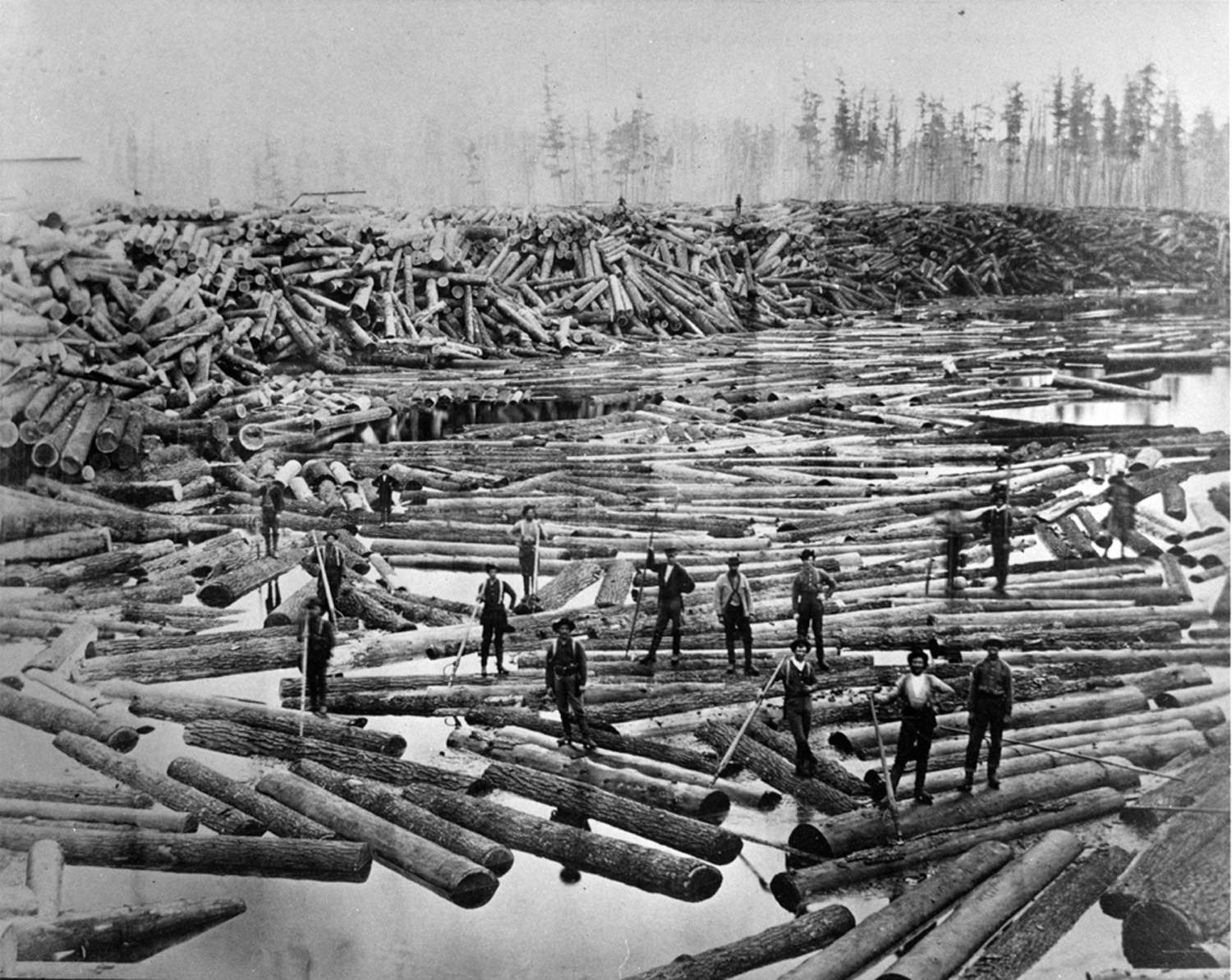

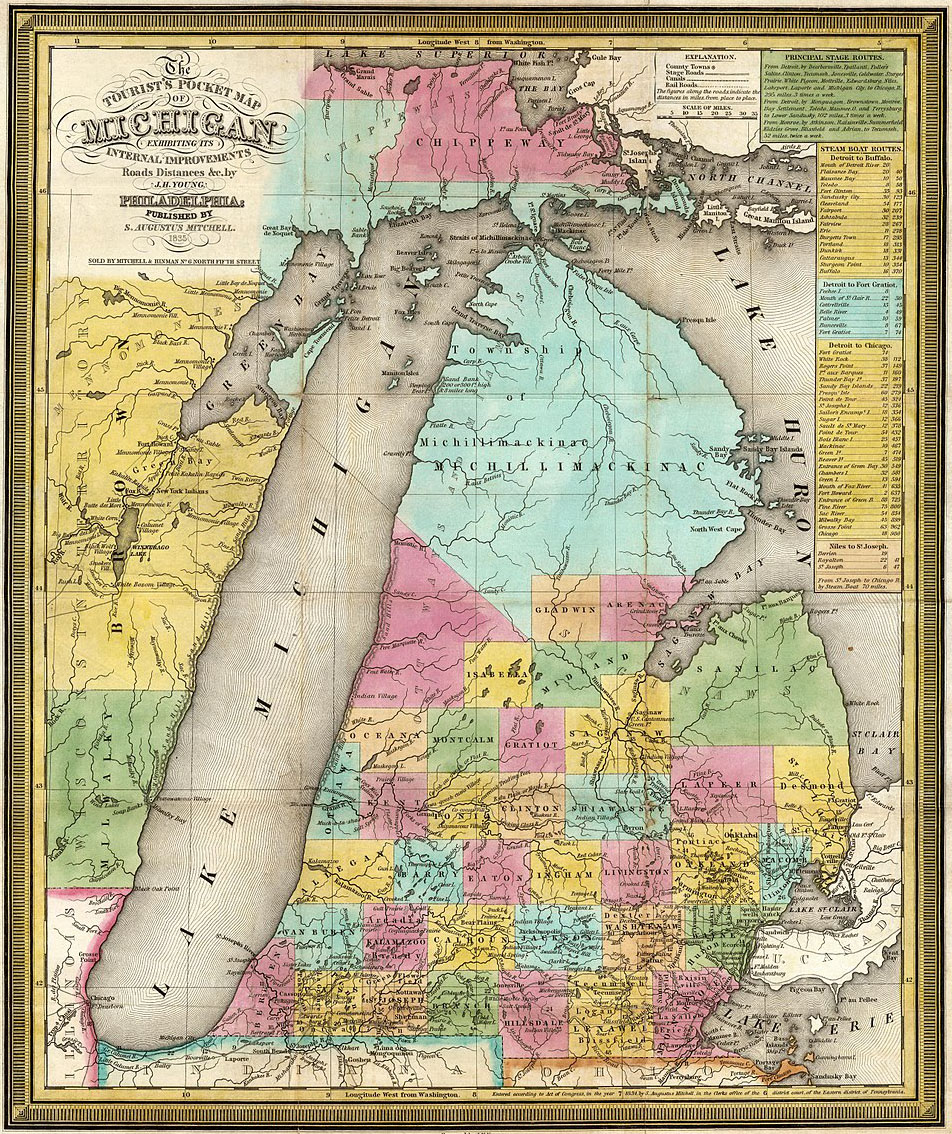

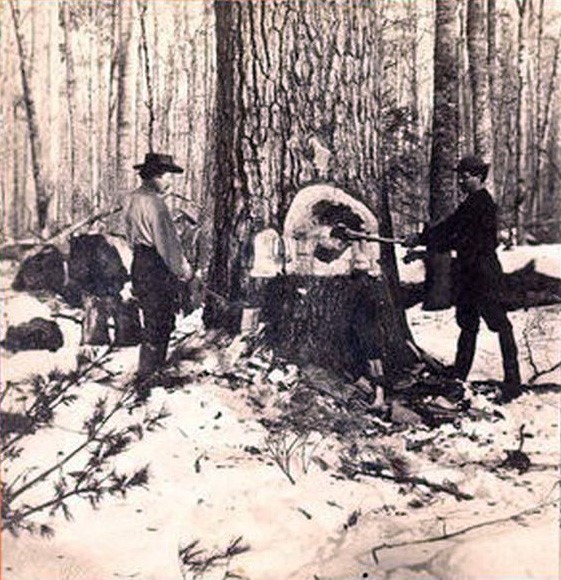

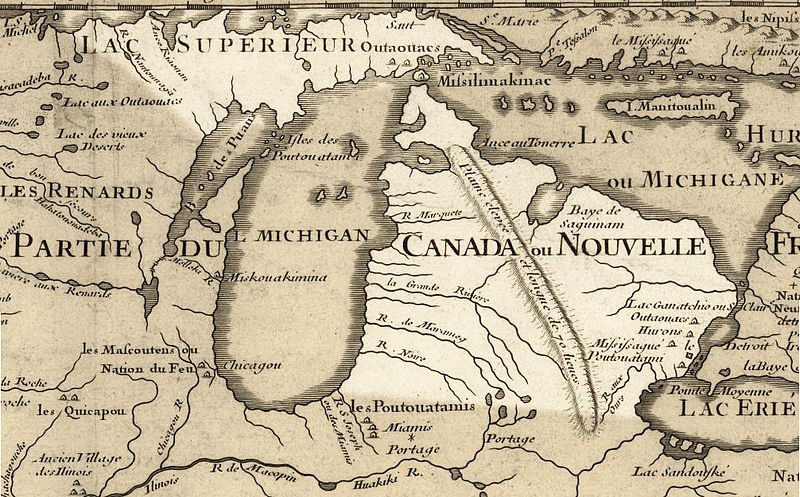

The French did the earliest lumbering to build forts, fur-trading posts, and missions. The British, and later the Americans, used Michigan’s hardwoods to build merchant and warships. Beginning about 1855, white pine became the most desired tree species by the lumber industry of the Great Lakes states. Navigable rivers and extensive pine forests formed the basis of a flourishing pine industry in Michigan.

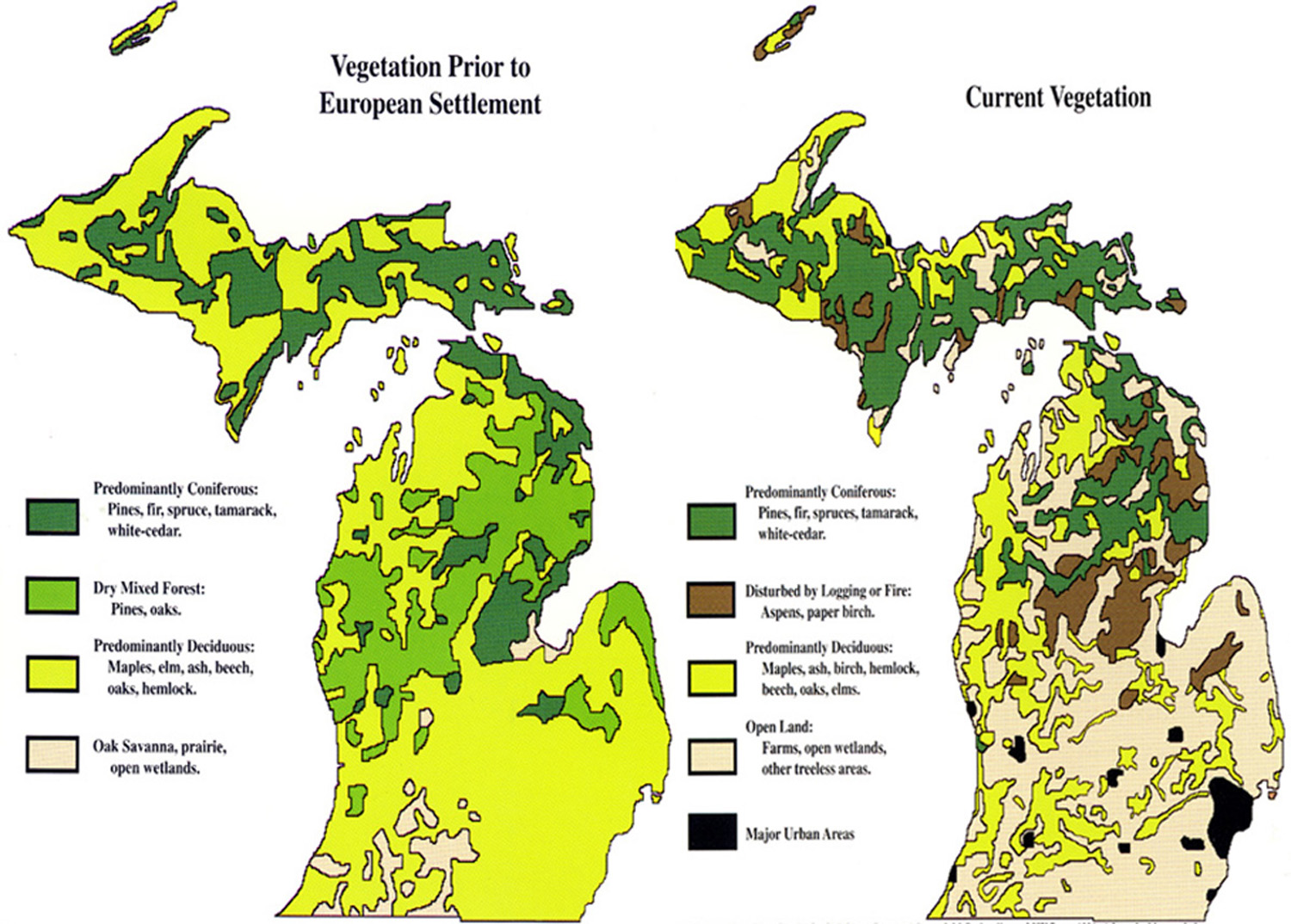

The history of trees in Michigan

North of an imaginary line from Muskegon to Saginaw, the White, Jack, and Norway pines grew, as well as other conifers (a tree that bears cones and needles). Conifers were the main softwood tree cut by the lumberjacks for the construction of homes, barns, and commercial buildings.

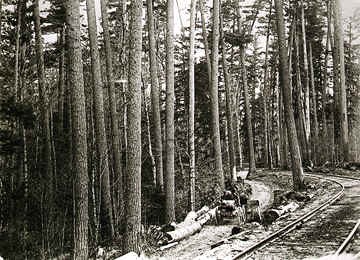

White pine logging camp

Turpentine, resins, and other essential consumer products were made from these trees, making them vulnerable to the ax and saw. It was the white pine that allowed the heyday of the lumber industry. Many white pines were over 200 years old, two hundred feet in height, and five feet in diameter.

Logging white pine in Michigan

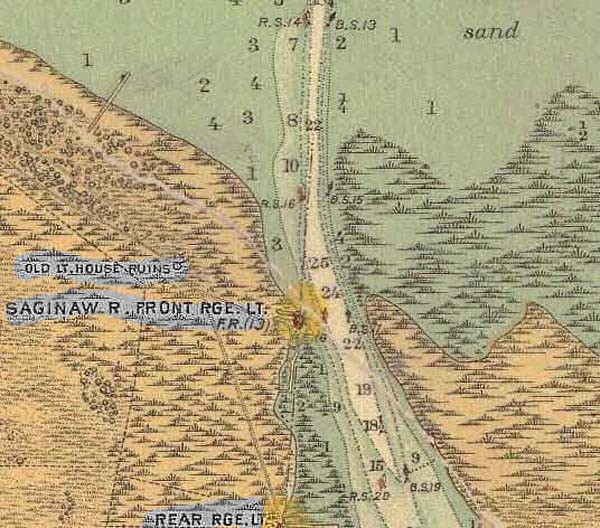

Michigan’s pine became necessary as the supply of trees in the northeast was used. By 1880, Michigan was producing as much lumber as the next three states combined. The first area where many mills were built was Saginaw. Six rivers converge to form the Saginaw River, which empties into Saginaw Bay and then Lake Huron.

The entrance to Saginaw River

The rivers are Chippewa, Tittabawassee, Cass, Bad, Shiawassee, and Flint. Streams played a vital part for the loggers because the lumber had to be floated to the mills and then to market.

Beginning of the log drive, Grand Rapids, Circa 1890s

The first group of people to set up lumbering operations were from New England, especially Maine and New York. The forests there were almost entirely cut, so the owners and experienced crews followed the work. Many felt that the vast forests of Michigan would last for many, many years, yet within 20 years, 1870 to 1890, most of the trees were cut.

Over cut forest

While David Knauss was working on the railroad line that runs from Illinois up thru lower Michigan, he attended a family reunion. Like all the other ones, it was a great time to get up to date on how the rest of the Knauss family was doing.

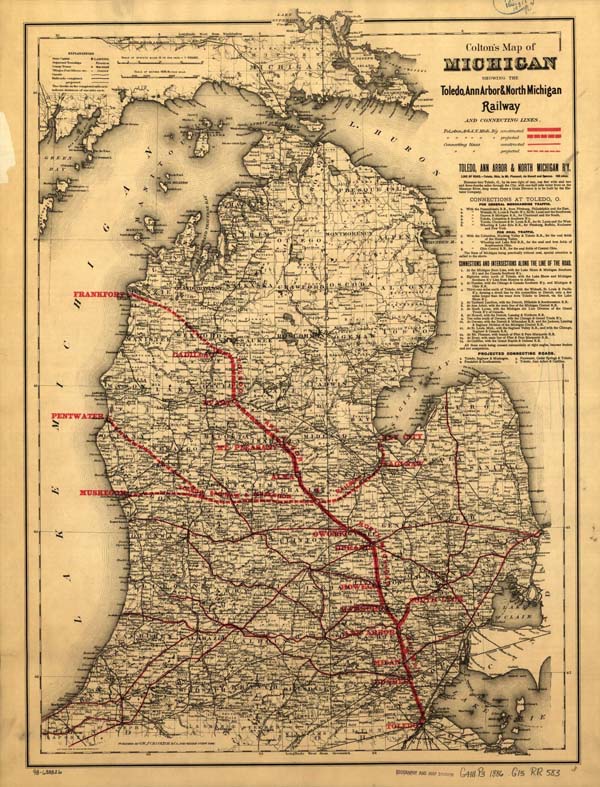

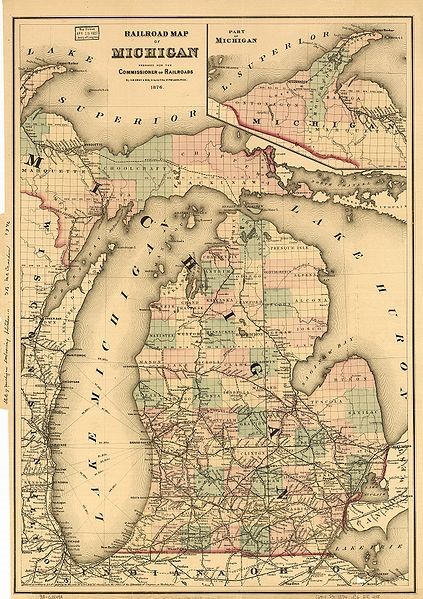

Michigan Railway map

David was not too comfortable socializing, but he did enjoy playing his fiddle with the other musicians. They would all sit in a circle with guitars, fiddles, and flutes playing songs till after dark. David brought his instrument with him, and he let it do the talking for him because he was quite a good fiddler.

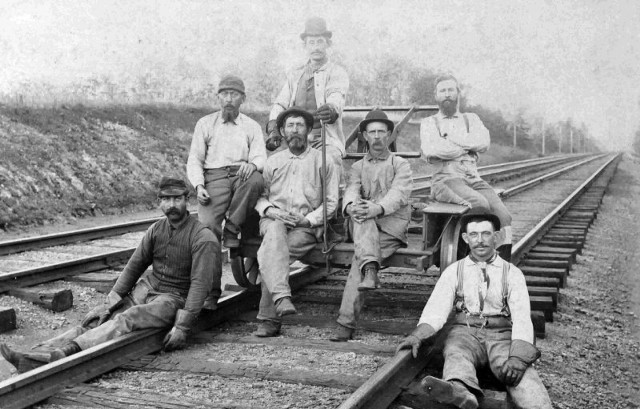

Railroad workers

But when the music was over, he found himself at a picnic table talking to Amos and Mary Knauss with their son Edward Knauss (1876 to 1952, great-grandfather). They had invited him to sit and have some pie and homemade cheese with them.

Edward Knauss place of birth

While they were eating, David asked Amos, “So how did you get to Michigan?”

Amos said, “Our family traveled up to Albany by wagon. Then we boarded a flatboat and took the canal to Buffalo, and another boat took us to Detroit. From Detroit, we went by wagon, cutting our way through on an Indian trail from Grand Blanc to Flint.”

Horse power

Amos took out of his pocket a small folded piece of paper. He opened it and showed David a crude hand-drawn map, and he used it to explain the trip.

Amos pointed to a spot on the map, “I bought 125 acres of land along the Flint River. There was some good bottom land, some still standing timber, and some land with stumps that need clearing.”

Remove the stumps and find a farm

David never had much to say; he was always a quiet person and more so now after the war. The family members had gotten accustomed to him, not always commenting or being part of a two-way conversation. But when he did speak, he often used German words and phrases.

1822 Michigan map

Amos continued telling David everything he could about the family, “The trip was rough on everybody. We could only bring a few household goods, my grandfather’s clock, and his wonderful bible full of the Knauss family’s history. Grandfather cherished it highly because of the many notations about the family’s history that had been written down by the generations before him. He was not only religiously inclined, but he was quite literary.”

Pioneers on the move

David looked at the map that was still in Amos’s hand, and he asked, “Are you still living here?” pointing to the spot on the map.

Amos brought him up to date with his family’s new home. “In 1876, after our son Edward was born, we sold the farm along the Flint River. We headed west to the old abandoned Indian Fields on the trail that runs along the Kalamazoo River.”

Amos used his homemade map again to show David a different spot where his family had moved to. “It was very hard on Mary to make a move so soon after childbirth.”

Michigan Railroad Map 1876

The conversation sparked Mary’s interest, and she spoke up, “When we first got there, the only shelter we had was a tent we made from the wagon cover.”

She looked directly at Amos and gave him a smirky grin, “We have seen what happens when the men in the Knauss family get pioneer fever; they move.”

Amos had no defense, and he did not try to cover what happens to the family when he gets pioneer fever, so he agreed, “Yes, honey, you are right.” To avoid talking anymore about his family moving again, he asked David, “What are your plans for the future? Are you going back to Pennsylvania?”

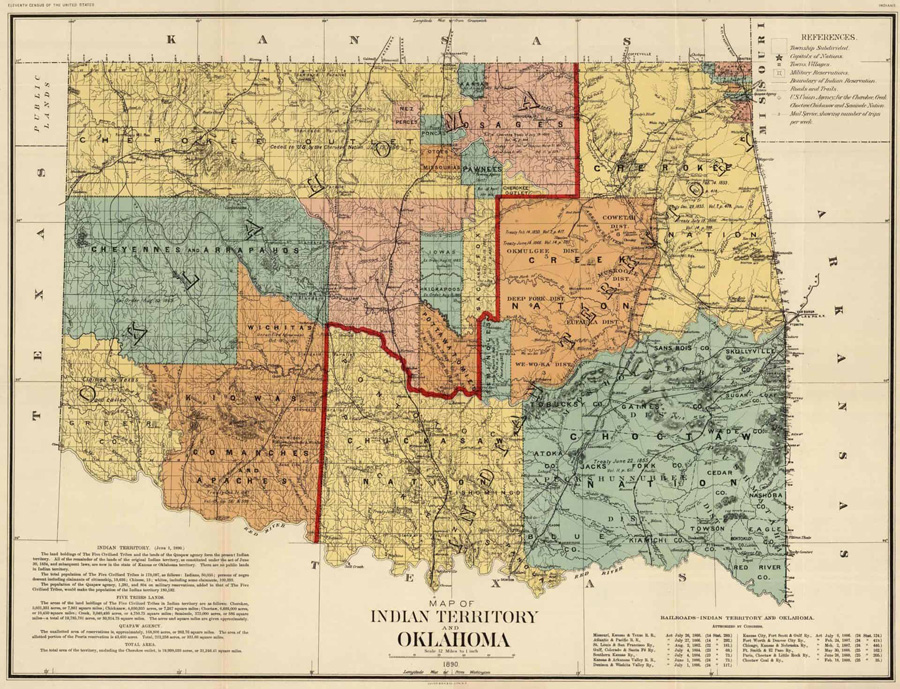

David thought for a moment and said, “I have some friends from the war that moved west to Kansas now that it is a free state. Thinking about going west and buy me some of that Indian land, the government is homesteading to farmers. I’m a farmer, not a railroad man, and I need to get my hands back in the dirt.”

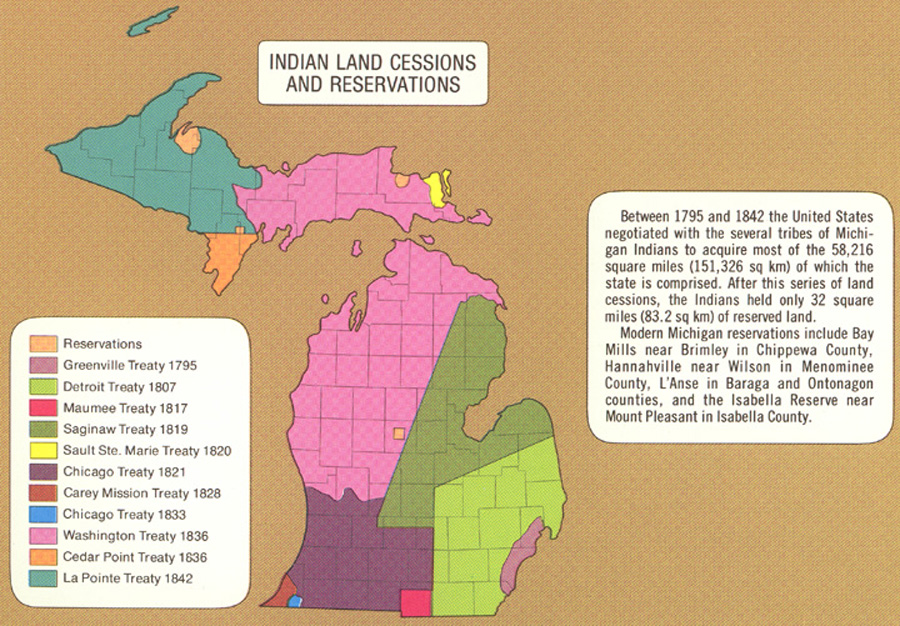

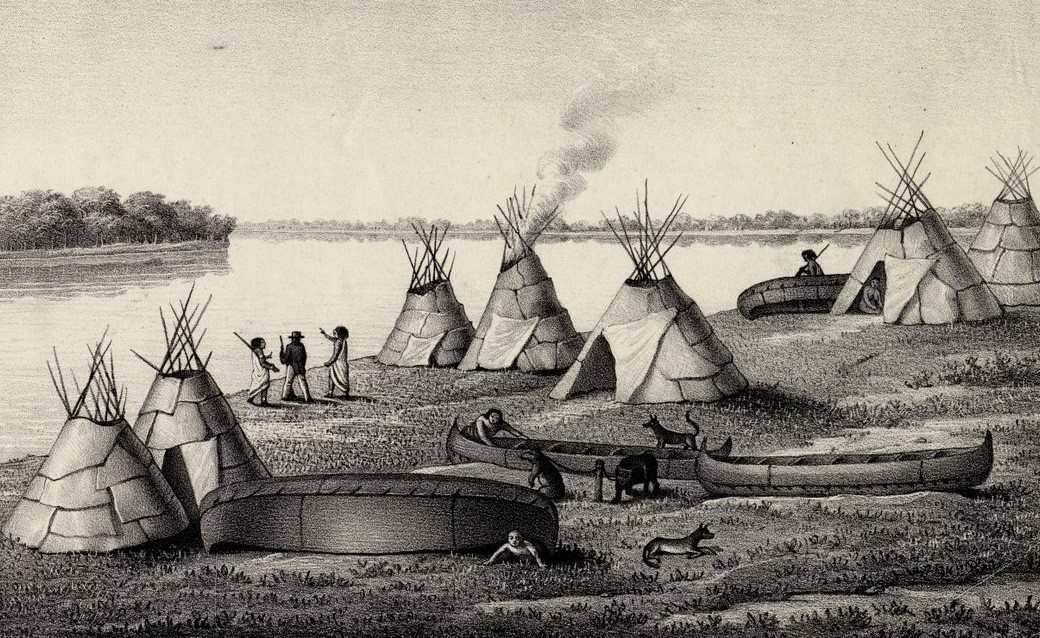

Indian land treaties

Amos spoke again, “Where we live now, some of our neighbors are Indians. They helped us get in our first year’s crops, and our yield was quite bountiful, which we shared with them.”

Amos went on to say, “Edward goes to school and plays with their children. He is even learning their language, and he is teaching it to Mary and me.”

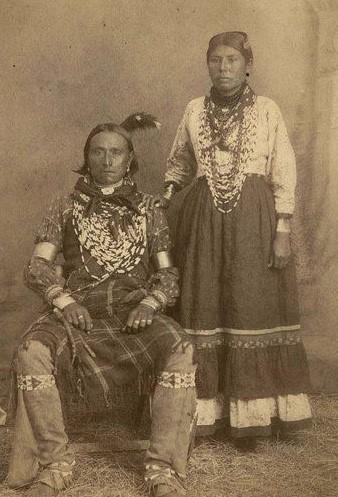

Mary spoke up, “We have found them to be a very hospitable and trustworthy people. Sadly, the Indians contracted smallpox, and most of them died. They never had any white man’s contagious diseases before, and it killed them off rapidly.”

Oklahoma Indian Territory

David did not know how to respond because he had not yet had any personal contact or relationship with the Native Americans, and he only knew what he had heard about them, and it was not good.

Potawatomi couple

As they talked, they all knew they had seen better times, but each one was hopeful for a better day to come. They departed that day from the family reunion. Dave headed west as far as the rails could take him. He settled in Stillwater, Oklahoma. David Knauss died in 1920 at the age of 77, and he was buried in Lyons, Kansas.

David Knauss – Indian Territory and Oklahoma 1890

Amos, Mary, and their son Edward returned to their farm along the Kalamazoo River. Edward was their only child, and they spoiled him. Mary was a great storyteller, and Edward loved to hear her talk about his family and the people that came before them. Mary told stories mostly about her family, the Shingledeckers, and how they got to Michigan. When Mary was young, her grandmother was the storyteller in the family, and Mary would repeat these stories to Edward.

Michigan’s American Indian Heritage

Hearing these bedtime stories connected Edward directly to Knauss families from the past. His mother spoke with authority and about her personal experience. Mary’s grandmother had instilled in her how important it was to pass the family’s history to the next generation. She loved to talk to Edward about her grandmother, and he enjoyed listening to her.

Edward had caught a nasty cold that led to pneumonia, an infection that inflames the air sacs in the lungs. He had a fever, the chills, and he coughed up a lot of phlegm. Mary spent most of three nights telling him the stories her grandmother told her long ago.

A sick child

The first night he got sick was the roughest for Edward because he did not sleep once in 24 hours. His coughing kept him awake, and he was just too ill to sleep. Mary, his mother, tried to comfort him the best she could. She gave him a mixture of whiskey and honey to help him with the nasty cough. And she wrapped him tight in blankets to keep him warm enough to break the fever with a good sweat. Mary did what her mother always did; she made an onion poultice and hung it around Edward’s neck. Then she gave him some sassafras tea with hot fresh biscuits.

Mary sat on the edge of Edward’s bed and held her son’s head in her lap. As she looked down at his watery eyes, she saw both hers and Amos’s face in his. “How much children look like their mothers and fathers,” she thought to herself. She wished there was something else she could do to make her child feel better and be well again. And there was something else she could do. She could have a word of prayer with the boy.

“Edward.” she said, “Edward, let’s say a little prayer together that the Lord will make you feel better, ok?”

Edward did not answer, but he did nod his head in approval.

Mary started by saying, “Our precious heavenly Father, we know you are the creator of all things. We know you love us because you sent your Son to save our son and us from sin. We know this because of the good news written in the Gospels. We know that all our troubles can be put into a basket at your feet, and you will take care of us. We know you are the great physician and healer. We ask you now to heal Edward. Ease his discomfort. Encourage him through this time. Bless him and make him well again. In Jesus’s name, we pray, Amen.”

Jesus the great physician

When Mary opened her eyes, she could see that Edward’s hands were folded, and he was praying his own prayer. He said, “And God bless mama too, Amen.”

The young man could hardly say anything, but he did say, “I love you, mama,” and closed his eyes, still resting his head on his mother’s lap. With his eyes still closed, he asked, “Please tell me the story about when grandma first came to Michigan again.”

A mother and child praying

This tale had been told many times before. Once when Mary’s grandma told it to Mary’s mother, once when Mary’s mother said it to her, and more than once, Mary had told this story to Edward.

Mary remembered the stories from her childhood very well, and she was able to give a detailed account of each incident in her grandmother’s experiences. She told Edward about her conversations with her grandma, and he pretended to be right there with them.

One day when Mary was spending time with her 81-year-old grandma, Mary asked her, “What was it like when you first came to Michigan?”

Her grandma thought for a moment, then smiled and said this, “My family first came to Michigan on a soldier’s pension promise. The U.S. government promised free land in Michigan to any veteran of the Revolutionary War, although they did not expect many to claim it, my father did. He grew into manhood while in the war at the age of 18 as a captain of a rifle company. He served at the place that was his home until pioneer fever sprung up in him. After the war, he had some money saved, and he bought a small farm100 miles away in west Pennsylvania.”

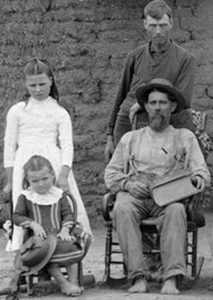

A pioneer family

New England

Grandma told Mary she was only about three years old when her family left their home and moved to Michigan. “My father, I called him Papa, was took-down with the pioneer fever again, and in 1841 he got an itching to move to someplace new. So, he sold his farm and loaded all he possessed into his lumber wagon along with a few chickens, two piglets, one wife, and five children. With a good team of horses pulling the wagon and two cows in tow, he headed towards the frontier of Michigan.”

Michigan 1835

Grandma went on to say, “I don’t remember how old I was at the time, but I had not started school lessons yet so, I was younger than five years old.” When she paused, you could see a spark of joy in her eyes as the older lady remembered, the younger one.

Then she chuckled, “I rode in the wagon sitting in my chair on top of everything else. When a wheel fell off while going over a big dead log, the chair was tossed off the load with me still in it. Everything in the wagon spilled out all over me.”

She told how her father was more scared than she was, and it was the first and only time she saw him cry tears of fear. From then on, her father kept her by his side on the wagon seat during the day, and she was put to sleep at his feet each night.

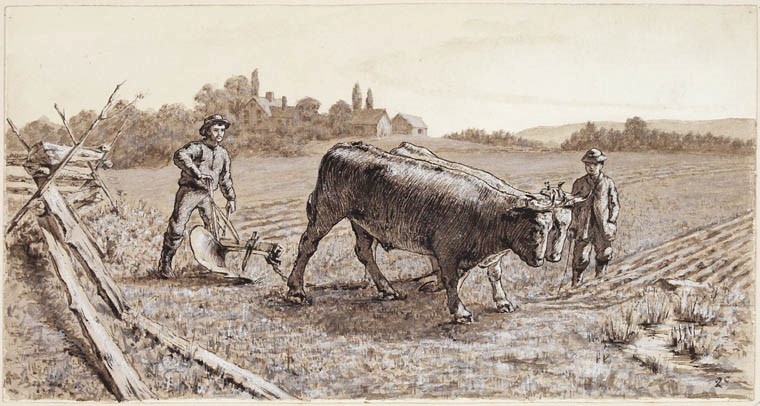

Like many other pioneer families, they were looking to clear good farmland of the stumps left by the lumbermen that had cut down the trees a few years before. Michigan was a dense forest of Basswood, White Pine, and Black Walnut trees, sometimes four feet in diameter. Using only a hand ax, the trees that still stood were cut and burned to clear the land for the plow.

Plowing with Oxen

Grandma explained that “Burning up these great trees would sometimes take two weeks or longer if the logs were green wood.”

She went on to say that her father oversaw the ashery, and he collected the ashes of the trees after they were burned. The ashes were used to make Saleratus, and it was sold as a replacement for baking powder for 10 to 12 cents/bushel. The ashes contained a natural form of sodium bicarbonate that made baked goods like biscuits rise.

You could see the sadness in grandma’s eyes as she said, “These great monarchs of the forest were felled to make a place to sow the wheat, flax, and potatoes for the family’s survival. How we would like to see them growing still today.”

The forest before trees fell

She went on telling how her father cleared a few acres, and the soil was made tillable for farming. It gave the family a small living, but they still relied on the forest all around them for fish and game. Grandma explained, “Papa used the logs from the trees he cut down to build a small cabin in the middle of the cleared land, and he made a lean-to for the animals.”

A lean-to for the animals

Great monarchs of the forest

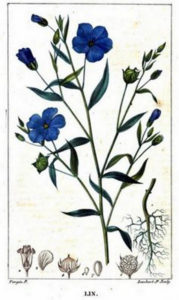

Grandma described what was done next, “After the ashes were collected and the ground laid bare, we all helped break up the moist soil with a rake, shovels or whatever we could find so it could be planted.” Food was not the only thing that the early farmers planted, Flax was started from seed, and it was used in making cloth and other household articles.

A Flax hackle

There was the same respectful tone in her voice each time grandma mentioned something to do with her father. “Papa cut down each tree, split each rail, and made every board used to make our cabin all by himself.”

Pioneer families lived far apart from each other, and sometimes the closest neighbor could be over 20 miles away. These were families living alone and totally dependent on their own self-effort to survive in the yet untamed forests. These woodlands provided good hunting for squirrels, rabbits, deer, and moose for fresh meat. However, there was still bear, cougar, coyotes, and wolves living in the trees beyond the field grandma’s father had cleared.

Settlement in Michigan

Grandma described her home, “Papa built a fireplace in our cabin made from stones he had collected along the water’s edge. I used to help him pick out the ones he should use, and I helped carry them to the cabin. When the fireplace was done, and for a long time after, I could look at it and remember each stone and the fun I had that day playing in the water with papa.”

Cabin fireplace

Grandma told about one day when “Papa traded a young pig for an iron cookstove that had a large flat cooking surface and an oven with a door.”

Grandma went on to say how much they loved that stove and the bread and cakes that were baked in the oven. “From then on, a kettle sat on the stove, and Mama always had hot water for tea or coffee, and there was always warm water to wash up with.”

Grandma said that her “Mama sometimes kept a small kettle of potatoes in hot water for us kids to eat during the day.”

Grandma told a sad story about when she was too young to help herself, she tried anyway, and the kettle of potatoes overturned and spilled hot water all over her. She was severely scalded with the boiling water, and as an adult today, she still had the scars on her arms to prove it.

Grandma told about her mother, “I still can see my mother on her knees scrubbing the puncheon floor until it was white.” Many cabins had puncheons for the floor, which are split logs flattened on one side only. These ruff boards had many slivers that had to be scraped smooth before bare feet could walk on them.

“There were two beds put in one end of the cabin,” grandma said, “And my trundle bed was underneath.”

She spoke about how cold it got at night sleeping so close to the floor and how she was glad the dogs would lie real tight next to her. “I love the trundle bed song for it brings back good old memories which were full of privations yet dear to my heart,” and then grandma began to sing a song from her youth,

“As I rummage through the attic

Listening to the falling rain

As it pattered on the shingles

And against the windowpane

Peeping over chests and boxes

That with dust were thickly spread

Saw I in the furthest corner

What was once my trundle bed.”

A child’s trundle bed

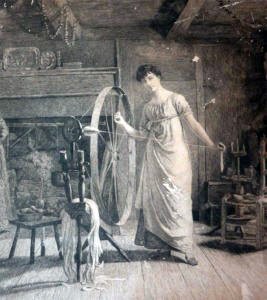

Grandma spoke again about her mother, “Mama was a weaver of cloth, and she was a fine seamstress. She hand-made all of our clothes and stitched them up when they wore out.” Grandma recalled that there was little room in the cabin because of her mother’s spinning wheel, quill wheel, and a small flax wheel.

A spinning wheel

Flax was a blue-flowered herbaceous plant cultivated for its seeds made into linseed oil, and textile fibbers could be made from the stalks. Flax was almost always the first crop to be planted because of its many household uses. Wool was preferred over Flax for articles of clothing for young and old because it was warm and long-lasting. Flax could be cultivated, spun, and woven into cloth when sheep were not available for wool.

Flax flower

Grandma shared a fond memory, “One year Mama made me a brand new wool dress. She said that my last year’s dress, which had been spun and woven in the home, would be good enough for school. The new dress was decorated with red cloth at the bottom, and it just swished across the floor as I walked. Mama had stitched a small piece of lace at the neck and the cuff of each sleeve.”

Grandma said that later she saw that Mama had cut the lace off one of her best dresses to make the new one for her. Grandma said, “I was so excited to go to Church dressed so fine.”

“When papa could get wool, Mama would make us nice warm stockings and scarfs. One year she made papa a wool coat, and he hardly ever took it off during the winter months,” Grandma chuckled again.

Grandma’s memory was good, and she recalled, “My father and mother each had their own chair they had brought with them from back east in the lumber wagon. These were larger chairs than mine made for adults, and they were most prized by mama and papa.”

Grandma went on to say, “At the end of the day, having a comfortable place to sit as the sun went down was very pleasurable, especially in your own chair.”

Pioneer chairs

“Most of the time, children sat on stools or benches made of rough sawed boards,” Grandma said. “One day, papa came back from trading with the backs and frames of six chairs, and he made splints of ash wood for the seats.”

The far-off look in Grandma’s eyes gave away that she was deep in thought. Then she said, “We were a proud family when we got new chairs. Even though they were not overstuffed, we were proud of those new chairs.”

Edward’s coughing interrupted his mother’s story, and Mary stopped to adjust his blankets and get him some more sassafras tea. He had not eaten any of the first biscuit, so she did not get him another.

She told him, “Son, you must try to eat something even if you don’t feel like it. You must keep up your strength.”

Edward moaned, “But I’m not hungry, …cough…cough…” he sat up a little and said to his mother, “You did not finish the story yet.”

Bring home the cows

Mary told Edward that grandma shared her memories of what it was like to be a child back then when her family first came to Michigan. She said, “In my younger days, everyone in the family had to work together to scrape up a living, even the youngest.”

Grandma continued, “There were no fences around the cabin, so the cows were allowed to wander in the woods and search for food. Every night one of us kids was sent into the woods to find the cows and herd them back to the lean-to for milking time. It was hard to find anything in the thick undergrowth, even something as large as a milk cow.”

Then Grandma told a little secret, “The leader of the herd was named May Bell because papa had tied a bell around her neck, and this made it easier to find the cows in the brush.”

Grandma spoke really soft when she went on to say, “It was terrifying! You did not know where you would find them or how long you would be out there. While searching for the cows, I saw many traces of torn down wigwams and paths made by the Indians as they roamed the forest or went to trade their game and furs at the trading post. At night you could hear the pack of coyote’s howl, but if they saw you, they usually would run the other way.

Indians of the Great Lakes

But when wolves were known to be in the area because they were heard howling in the night, papa would take his rifle and both dogs to bring in the livestock. Papa’s rifle was always kept above the cabin door within an easy reach. From an early age, papa taught us how to use and respect a gun. Everybody in the family could shoot very well, boys, girls, and mama.”

A pack of wolves

Grandma went on to tell about when, “One-night wolves were known to be in our neck of the woods, and papa heard the cows bellow like they were being threatened. We had already lost one young steer, and papa was not about to lose another to wild animals. He and the dogs took off, and very shortly, we heard shots from not far away. We could hear the dogs barking and papa yelling orders at them, but we could not understand what he was saying. We heard first one shot, then another, and the dogs kept on barking. Then we heard a single shot from his rifle, and then all was still. And we waited. And we waited.”

Grandma waited for a moment before continuing, “When we finally saw papa emerge from the woods, the dogs leading the way. He went straight to one of the horses and hitched up a tow rope. We ran over to find out what had happened. He told us that a big buck had tried to get a drink from the water where the cows drink each day. After so much time of the cows drinking in the same spot, their hoofs had cut up the bank so much it was a mud bog. The deer was unaware of the mud and had stepped right in. When the deer tried to jump out, it became stuck up to his neck in deeper mud and could not free itself. The deer’s bleating cries for help were heard by a grey wolf who was trying to reach the deer when papa arrived in this scene.”

Grandma said, “The wolf could not get to papa because of the mud bog between them, so it was an easy shot when papa put the wolf down, and he stopped him from suffering, with the second shot. The third shot we heard was when he killed the buck. Papa used the horse to drag the deer back to the cabin, and most of that night, we spent cutting up, salting, and smoking the venison. We also hung up strips of meat to dry on a rope between the cabin and the lean-to. This made delicious jerky for carrying with you when you travel. Papa mounted the 10-point deer antlers above the cabin door, and then he traded the wolf pelt for $5 and some supplies that we needed from the trading post. In those days, butter was 10 cents a pound, and eggs were 25 cents for three dozen.”

Fur traders

French fur traders map

Grandma said that she remembered that day because “me and my brothers and sisters all got candy the day we went to the trading post. It was a hard choice between licorice sticks or rock candy when you like them both. All in all, this time, the forest had paid off in benefits for the entire family, and we never heard or saw signs of a wolf around our cabin again.”

Time for some candy