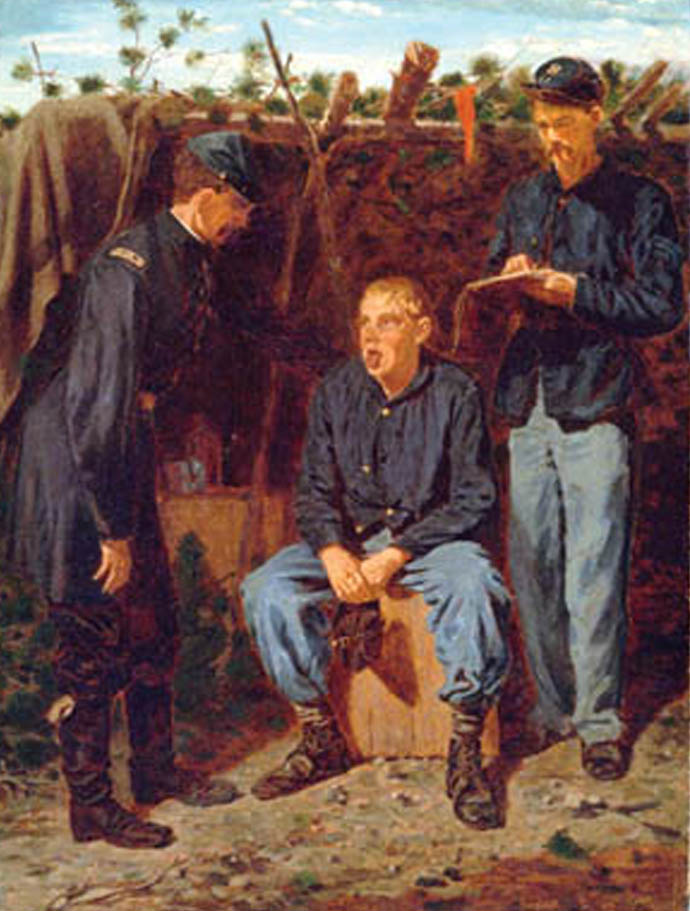

Rebel soldiers on the retreat

There was no time now to think about anything but trying to stay alive. As it so often happens in the fast-moving tide of war, the lines of battle shifted, and the Rebels were forced to make a hasty retreat in all directions. The only men left in the yard were like David, unable to move without some help, or already dead. The change in sides came so quickly all David noticed was the uniforms went from grey to blue, and soon the Union medics were treating his wounds.

He was pleased that the bleeding had stopped on its own. The mud had caked over the wounds like a clay bandage. It probably saved his life. One bullet had gone through his right pant leg, leaving a hole. But the other bulled had hit him in the left knee. The core man dressed and bandaged his wound, then he got David back on his feet, able to walk a little again.

a wounded Civil War soldier resting in a deserted war camp

The Doctor ordered him to be sent to Washington, where under kind treatment, he sufficiently recovered to return to light duty. After the rebels were repulsed, David was ordered to the War Department barracks. He did duty around the old Capitol Prison, and the Navy Yards Prison, where Mrs. Surratt and other accomplices of Pres. Lincoln’s assassination were confined.

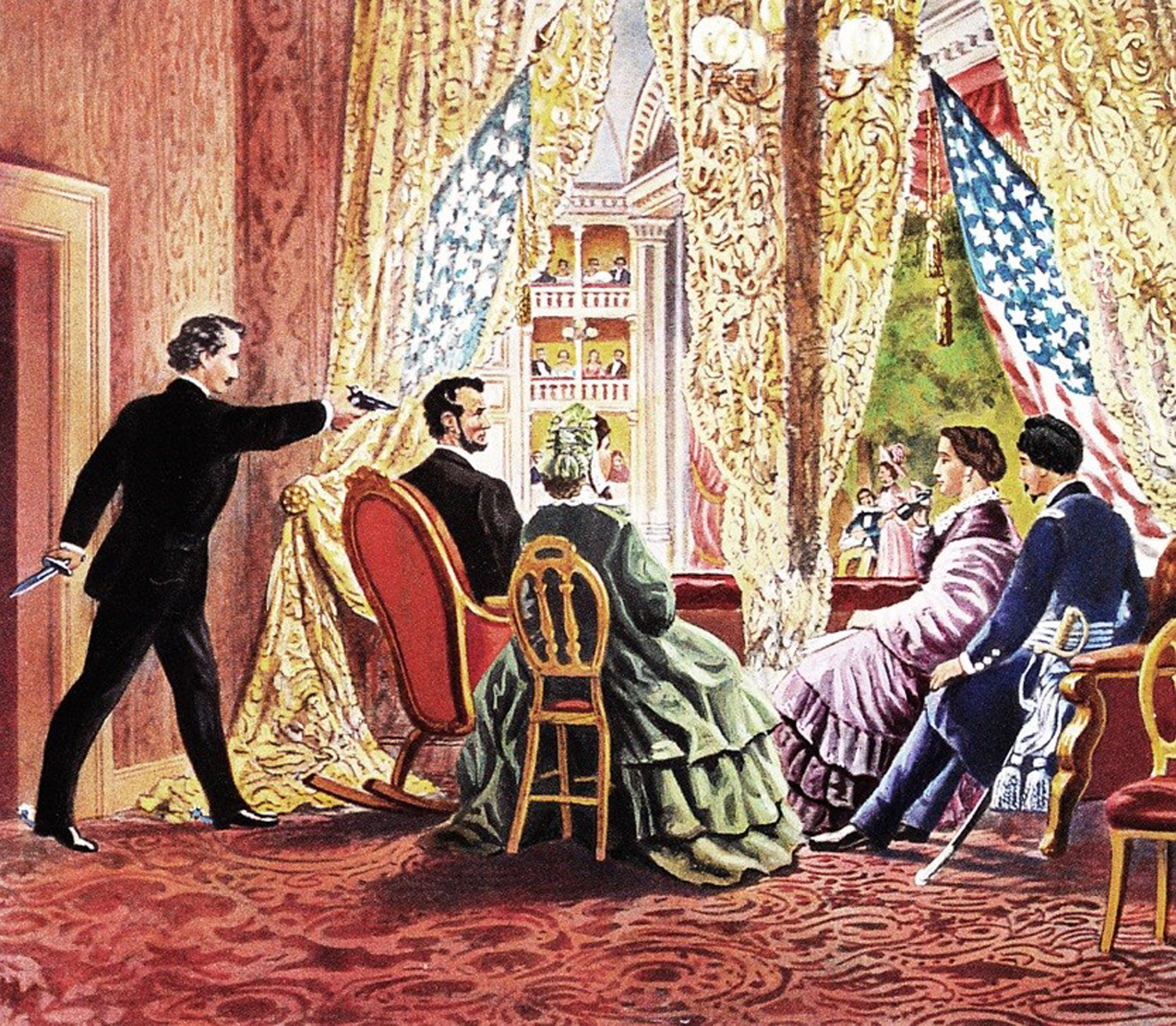

the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln – Washington D.C.

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on Good Friday, April 14, 1865. He was attending the play “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., just as the American Civil War was drawing to a close. The assassination occurred five days after the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army of the Potomac.

Lee and Grant meet in McLean front parlor to sign the terms of surrender

Timeline 1865 – 1866

Booth’s co-conspirators were Lewis Powell and David Herold, who were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward and George Atzerodt, who was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson. By simultaneously eliminating the top three people in the administration, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to disrupt the United States government.

from behind Booth shoot Lincoln – his escape path

As the President was watching the play, Booth shot Lincoln from behind at a distance of perhaps three or four feet, hitting him in the back of the head. At 7:22 a.m. the following day, Lincoln died in the Petersen House across the street from the theater.

Powell only wounds Seward

The rest of the conspirators’ plot failed; Powell only managed to wound Seward, while Atzerodt, Johnson’s would-be assassin, lost his nerve and fled. Booth made a dramatic escape, resulting in a lengthy manhunt that ended in his death. Several other conspirators were later tried and hanged.

the convicted

The regiment was mustered out of service, and on its arrival in Easton, the Colonel shared in the great ovation. The occasion will long linger in the memory of the survivors. The pleasure of the reception was significantly increased by the incident of the presentation of a beautiful sword, the gift of the officers and members of the regiment.

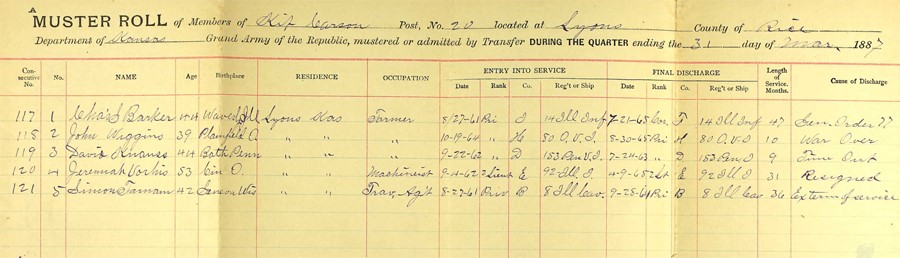

David Knauss mustered out of service

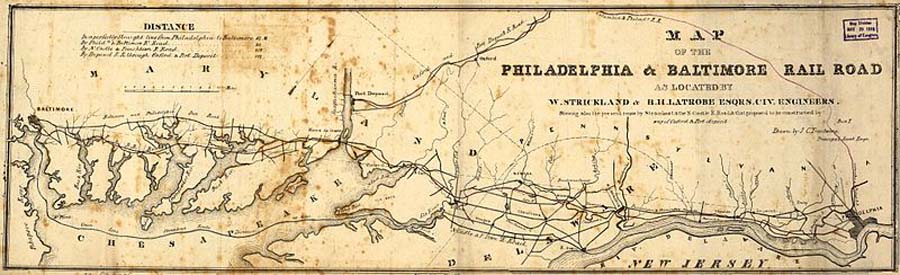

David and the troops boarded the train for Philadelphia and arrived in the city about 9 o’clock that night. Here they got tasty meals, had wounds dressed, but instead of taking a cot as the rest did, he lay down on the floor. About midnight, the fellows commenced getting out of their cots and complaining of backache, took positions on the floor. The beds were too soft for an old soldier. That night and the next morning, the trainload with which they came, was sent to West Philadelphia.

PW&B Railroad 1850’s

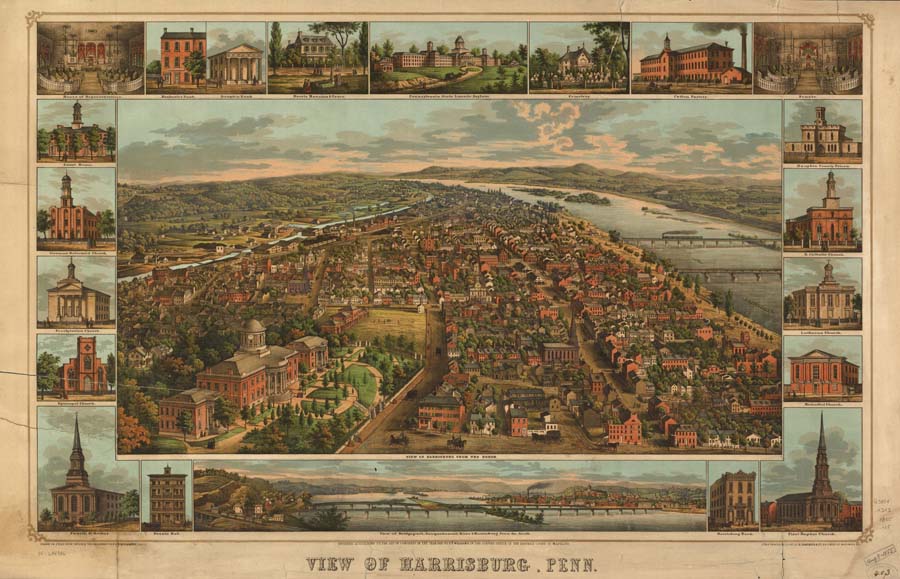

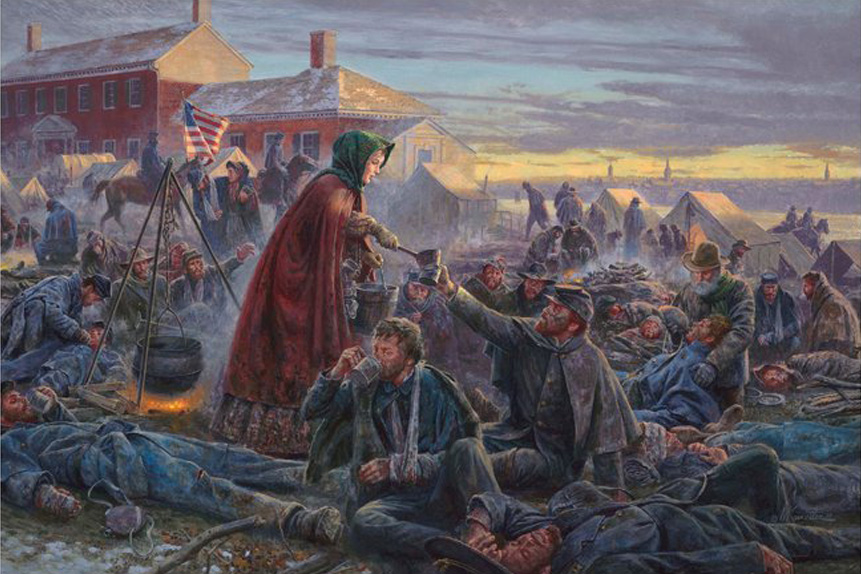

The men, twenty in number, belonging to the 153d Regiment, requested to be sent to Harrisburg, and their request was granted. After reporting to the general hospital, where they got dinner, they left for Harrisburg, arriving there that night at about 9 o’clock. The first thing they looked for was Uncle Sam’s boarding house, known in wartime as the Soldiers’ Retreat.

Harrisburg station

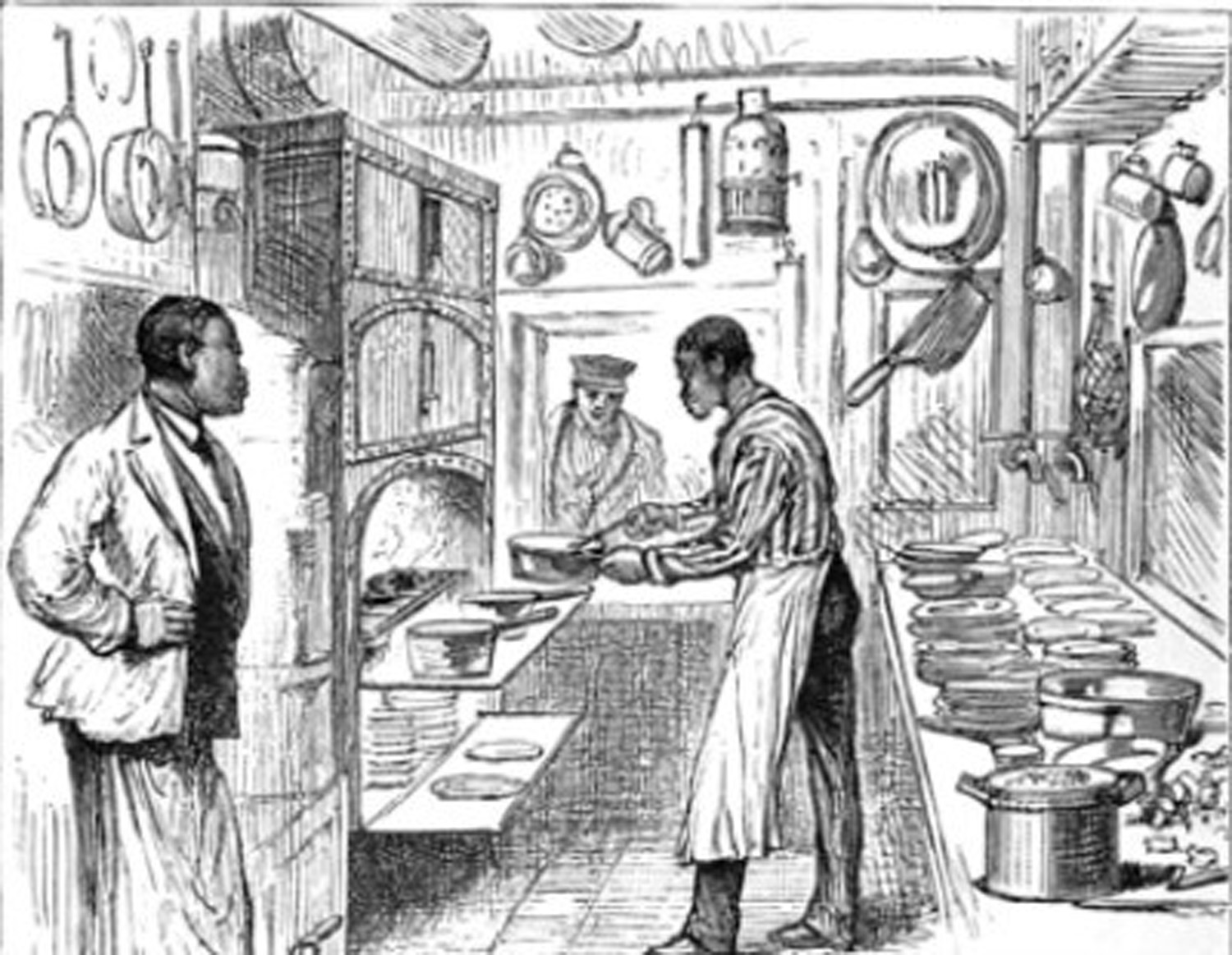

There was one corporal in the squad, and he was sent to the mess hall to see about supper. He came back and reported that the man in charge said that they could not have supper, because he was expecting a regiment of militia in that night. David’s crowd was composed of twenty men and a corporal. All the men looked ragged, bloody, and dirty. Some with heads tied up, some with arms in slings, some with crutches and canes. In fact, they looked as if they had seen service, had been to the front, and this report was not acceptable to any of them.

So, the men held a council of war, and it decided that they storm the retreat. There were two or three old pistols and revolvers in the crowd, but none of them were loaded. The men had no trouble with the guards, for they were on their side. The guards quickly passed them, and they got right to the front of the line.

the kitchen of a pullman Car

After the group got in a big old fellow made his appearance. He told them because they were not appropriately dressed, they could come so far on one table and no further. One of the fellows showed him an old revolver, and the big man got out of their way. The men ate all they wanted, then retired to look for a place to sleep. David had fully decided to report that gentleman in charge of the Retreat to the governor of the state. All the men found quarters for the night in a covered portion of the train depot.

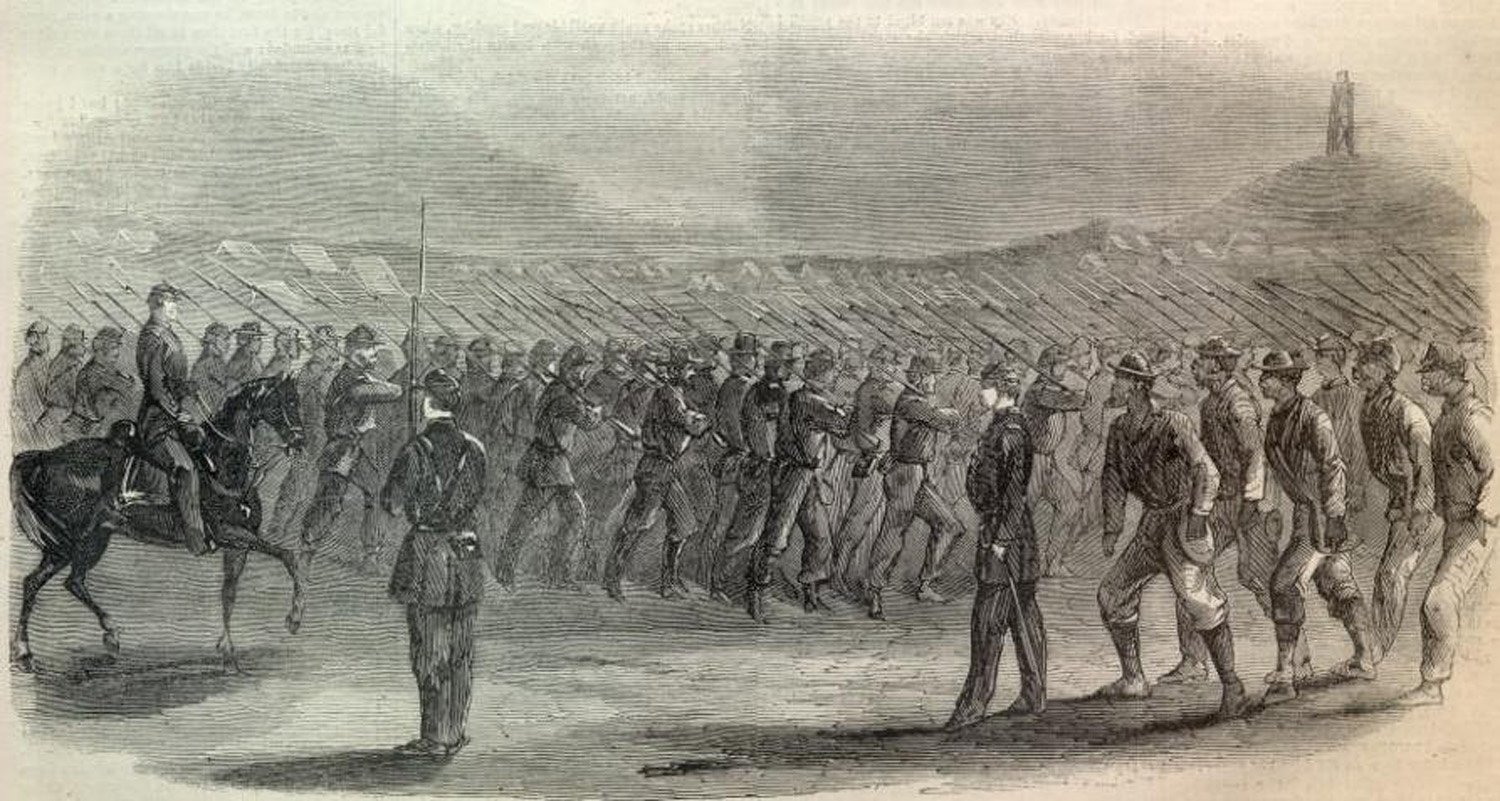

Just at daybreak, as David awoke, he heard commands, “Fall in.” The militia had arrived, which had been expected the evening before. He wondered what the mess hall was going to feed them after David’s men ate their meal. As they marched off, you could hear the officers calling, “left, left, left.” David said in a low voice to the other men, “they’ll find out.”

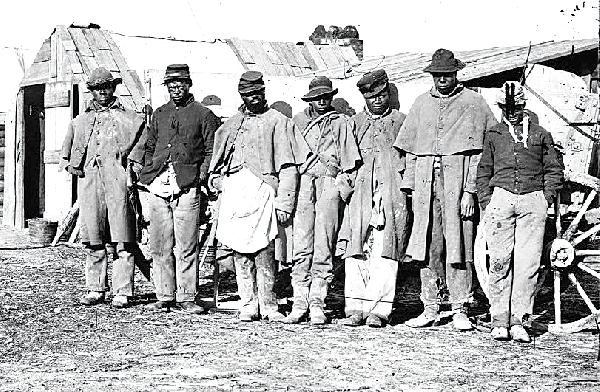

Union infantrymen

The men found water behind the depot, took a wash, and curled their hair. Soon after that, a messenger arrived, inviting them back to the Retreat for breakfast. It seems that the cook made an early meal for the militia, but they had left before it was ready to eat. The big old man apologized for his actions the night before. He said, “I was just a little off boys.” He took out his jug that softened their hearts, and they forgave him his sins for his whiskey.

having a drink

The Colonel joined the men and asked them how they were all doing. Someone in the back shouted to him, “It’s too hot and dry to talk much, sir.” The rest of the men were left in uncontrollable laughter. The Colonel offered to treat the men to a beer. And with great appreciation, all accepted.

A captain said to the Colonel, “There is only one man here left from my company.” David and the captain were seated at a table. He went over the list of his men, inquiring after everyone by name. David could only report to him either killed or wounded. There were only twelve left of the company after the battles. The tears rolled down both men’s cheeks. The Doctor returned with arrangements for the men, and they were placed in a hospital on Mulberry Street.

Harrisburg Pennsylvania 1855

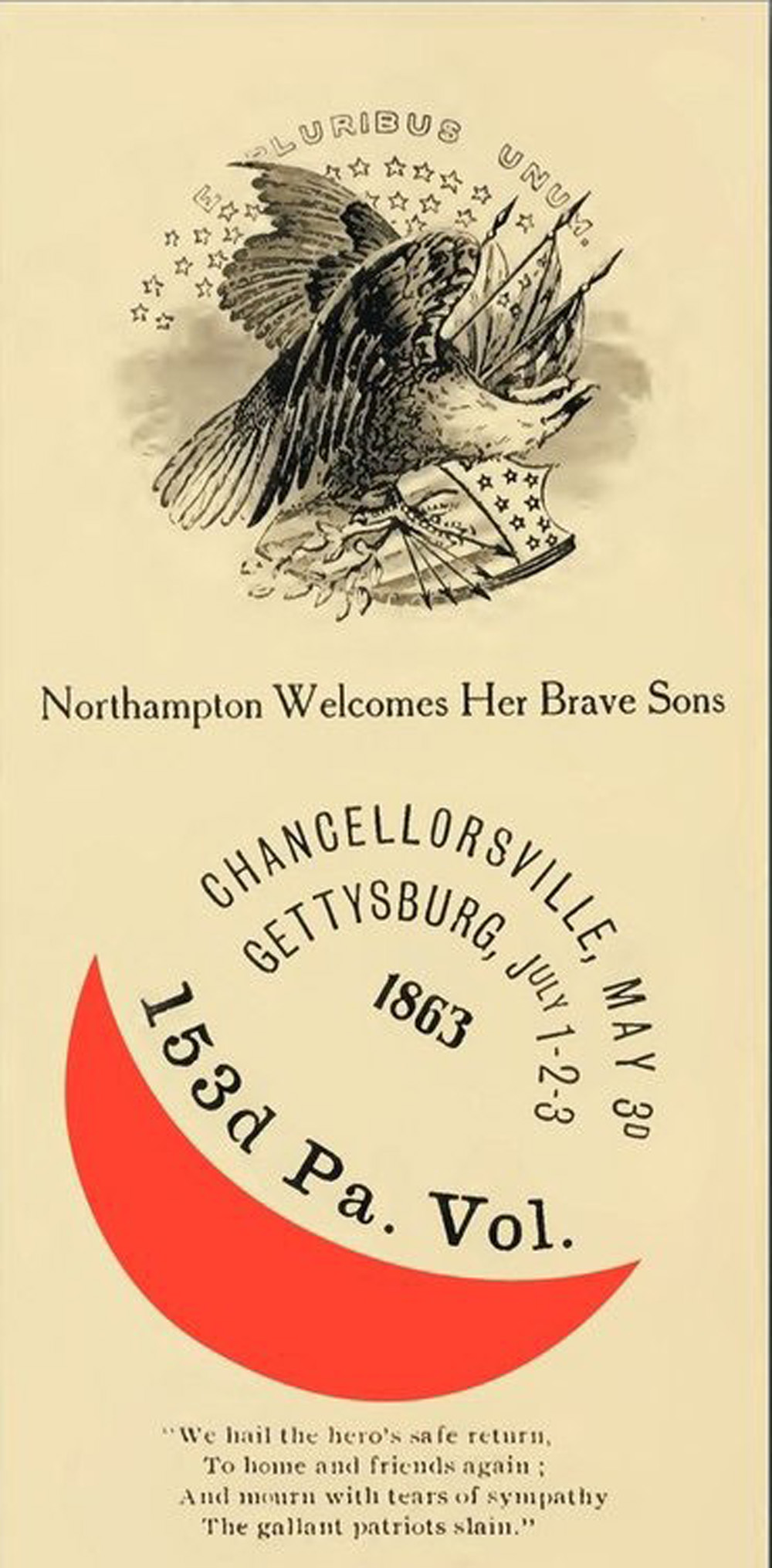

The regiment arrived in Harrisburg on the 17th. The citizens of the town treated the troops to everything to make them comfortable. Then the day came to return home. The first stop was at Reading. Here they were met by a committee from Easton, and they presented each man of the regiment with a badge of honor containing the corps mark, the battles they had been in, and the following poem.

Northampton Welcomes Her Brave Sons

We hail the hero’s safe return

To home and friends again

And mourn with tears of sympathy

The gallant patriots slain.

a grand welcome home

The boys were in fine spirits. The colors and their Brass Band was on the roof of the car. The next stop was Allentown Junction. David had informed Captain Stoul that he lived six miles up the valley from the Junction. He could not walk it and that he had no money. The Captain started through the car to see if he could find twenty cents for David’s fare. He returned with the twenty cents all in pennies. David told him, “from the looks of the change, he must have got all there was.” He said, “I would not undertake to get twenty cents more out of that crowd.”

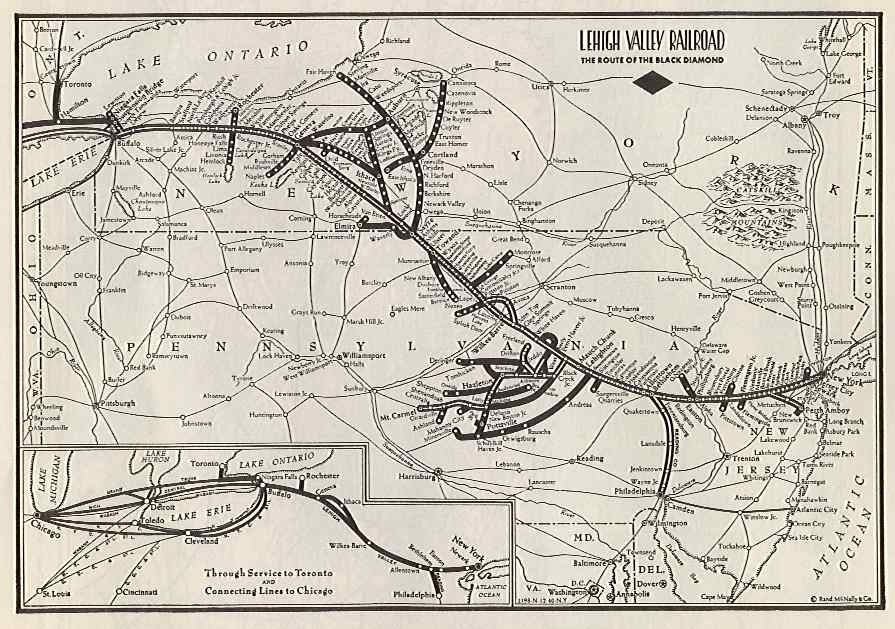

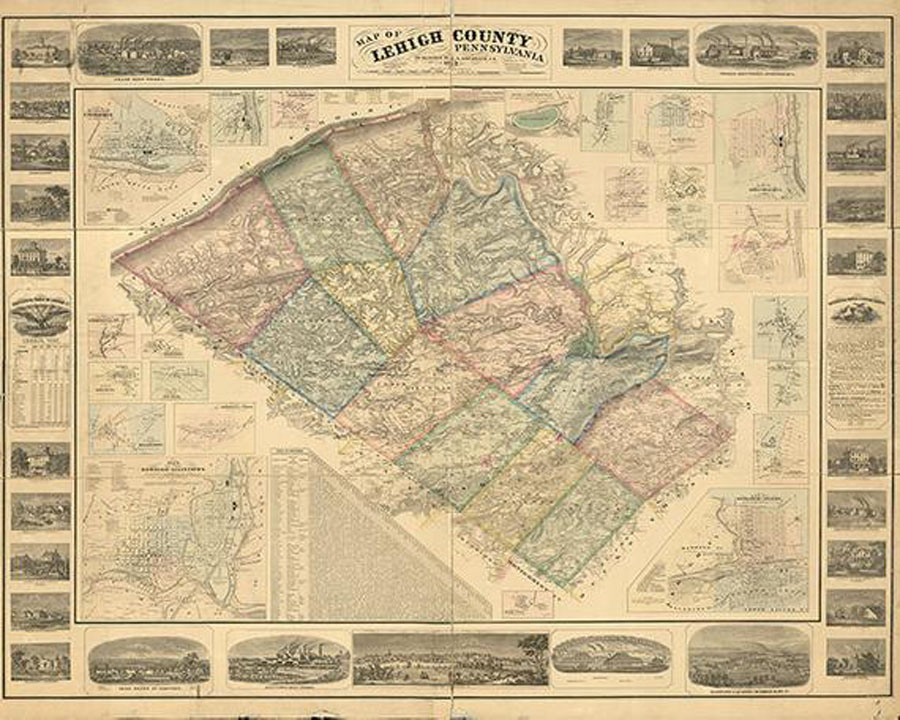

David and some of the men got off at the Junction, and by the time he got up to the Allentown Station, there were about twenty to go up the Lehigh Valley Railroad. They all expected to walk but David, for there were not twenty cents in that crowd, and he had it. But they were fortunate. An old man, his name was Lauhach, learned of their misfortune and bought tickets for all of the soldiers. David had been traveling two months without any money in his pocket, and he did not feel safe with twenty cents in the crowd I was in. The train came along, and they were soon at their destination.

Lehigh Valley Railroad Station – map

A coal train was passing at the time they arrived. Being between the station and the passenger train, and David not wanting to wait, he jumped out on the platform of the car. To his amazement, on the platform of the depot stood his mother and Rachel. They were expecting an uncle of his from New York City. In so little time, the living hell of war had changed David so much they did not recognize him. They could no longer see the vibrant youth that had jumped on the back of Henry the mule to ride off and enlist.

Civil War train station

The conductor was helping David off the train, and his medical tag on his back with his name was turned toward them. A young girl’s love spotted him, and Rachel was the first to call out his name. That was all it took, for the joy to see him, and the pain of seeing him, to overcome each of them into tears. No words can describe how glad they were to see each other. It was hard for any of them to speak. When their uncle got off the train, he offered to drive the wagon home. They never said a word about David running away and going into the army.

On the ride home from the station, David and Rachel set in the back of the wagon. David lay back on the straw to rest while she brought him up to speed on what’s been happening back home while he was away. He was exhausted, but he worked hard, keeping awake enough to listen to the latest news. They were constantly interrupted by his mother in the front seat, telling David one more thing sweet Rachel had been doing while he was away.

the ride home in a wagon

In the years before the Civil War, the lives of American women were shaped by a set of ideals that historians call “the Cult of True Womanhood.” The household became a new kind of place, a private feminized domestic sphere, a “haven in a heartless world.” “True women” devoted their lives to creating a clean, comfortable, nurturing home for their husbands and children.

cult of true womanhood

With the outbreak of war in 1861, women and men alike eagerly volunteered to fight for the cause. In the Northern states where Rachel and Ruth lived, women organized ladies’ aid societies to supply the Union troops with everything they needed. They baked, canned, and planted fruit and vegetable gardens to feed the soldiers. They sewed and laundered uniforms, knitted socks, and gloves, mended blankets and embroidered quilts and pillowcases. They organized door-to-door fundraising campaigns, county fairs, and performances of all kinds to raise money for medical supplies and other necessities.

women planting gardens

There were nearly 20,000 other women like Rachel that worked more directly for the Union war effort. Working-class white women and free and enslaved African American women worked as laundresses, cooks, and “matrons.” Some 3,000 middle-class white women worked as nurses. The war had given women a chance to control their own lives, earning their own money, and managing their own, finances. Some women were no longer complacently filling the roles they had filled before the war.

The activist Dorothea Dix, the superintendent of Army nurses, put out a call for responsible, maternal volunteers who would not distract the troops or behave in unseemly or unfeminine ways. Rachel was one of the many women, young and old, that responded with a “call to action.” Dix insisted that her nurses be “past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.” No one ever stopped Rachel from serving, her youth was overlooked.

Dorothea Dix,

One of the most famous of these Union nurses that Rachel read about would later write the book Little Women. Louisa May Alcott. While serving as a nurse, Alcott wrote several letters to her family in Concord. At the urging of others, she prepared them for publication, slightly altering and fictionalizing them. The narrator of the stories was renamed Tribulation Periwinkle, but the sketches are virtually authentic to Alcott’s real experiences.

Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott

Published in 1863, Hospital Sketches was a compilation of four sketches based on letters Louisa May Alcott sent home during the six weeks she spent as a volunteer nurse for the Union army. Tribulation Periwinkle opens the story by complaining, “I want something to do.” She dismisses suggestions to write a book, teach, get married, or start acting. Then someone suggests that she go, nurse, the soldiers, so she does just that. While attending to the wounded from the Battle of Fredericksburg, she converses with the various wounded soldiers, including an Irishman and a Virginia blacksmith. Witnessing his death affects her deeply.

Hospital Sketches, Louisa M Alcott 1863

It was not known to Rachel and the public that Alcott herself did not care much for the writings. She dismissed the idea that they were “witty,” and she admitted, “I wanted money.” The pieces received great critical and widespread acclaim making Alcott an overnight success.

John, a virginia blacksmith, from a later edition of Hospital Sketches

Army nurses travelled from hospital to hospital, providing “humane and efficient care for wounded, sick, and dying soldiers.” They also acted as mothers and housekeepers “havens in a heartless world,” for the soldiers under their care.

roles of women during the Civil War

The women of the south threw themselves into the war effort with the same zeal as Rachel and the other Northern counterparts. The Confederacy had less money and fewer resources than did the Union, however, so they did much of their work on their own or through local auxiliaries and relief societies. They, too, cooked and sewed for their boys. They provided uniforms, blankets, sandbags, and other supplies for entire regiments. They wrote letters to soldiers and worked as untrained nurses in makeshift hospitals. They even cared for wounded soldiers in their homes.

the role of women in society changed drastically on both sides

of the American Civil War, women went to work, some for the first time

There are three ingredients required to make gunpowder, saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur. Desperate for saltpeter, the Confederacy sent out agents around the South to collect deposits of “Night Soil.” John Harrelson, an agent in Selma, Alabama of the Confederate Nitro and Mining Bureau, advertised the following in the local paper: “The ladies of Selma are respectfully requested to preserve the chamber lye collected about their premises for the purpose of making nitro. A barrel will be sent around daily to collect it.” This appeal went out to the southern women to save the contents of their chamber pots.

making explosives

Many Southern women, especially wealthy ones, relied on slaves for everything and had never had to do much work. However, even they were forced by the exigencies of wartime to expand their definitions of “proper” female behaviour.

women in the South working for the war effort

Slave women were, of course, not free to contribute to the Union cause. They never had the luxury of “true womanhood” to begin with. Being a woman never saved a single female slave from hard labor, beatings, assault, family separation, and death.” The Civil War promised freedom, but it also added to these women’s burden. In addition to their plantation and household labor, many slave women had to do the work of their husbands and partners too.

work was never done for the slave women

The Confederate Army frequently impressed male slaves, and slaveowners fleeing from Union troops often took their valuable male slaves, but not women and children with them. Working-class white women had a similar experience. While their husbands, fathers, and brothers fought in the Army, they were left to provide for their families on their own.

black Confederate soldiers

Rachel told David that Ruth and one of his cousins got married just before the Battle of Chancellorsville. He was a year younger than Ruth but 6 inches taller and 50 pounds heavier. Rachel could still see in her mind, him picking up her sister, and sweeping her off her feet in his huge arms. Rachel told David that the two of them were in love from an early age, but everyone already knew that, including David. His family all thought they were going to get hitched someday. His family could also see that Rachel had her eye out for David, but he did not know it. If he did, he did not show it.

a Civil War wedding

David could see the sadness of their separation, in Rachel’s face when she told him that Ruth had gone along with her husband when he went on the march in the army. She travelled with many other men and woman that were camp followers. They supported the soldiers as cooks, nurses, blacksmiths, Sutters, and keep the army clean doing the laundry. Ruth had gone to war in order to share in trials of her beloved husband. She was also stirred by a thirst for adventure.

camp life

David took a deep breath, and he got really silent when Rachel told him what happened shortly after they got married. The change in her voice triggered his sigh, as she told him about Ruth losing her husband at the Battle of Gettysburg. David felt very sad about the loss of another family member and her husband. His feelings of sadness quickly changed to complete shocked when she told him what Ruth did next. Rachel almost shouted when she told him, “before the week was over, she cut off her hair, put on her husband’s military clothes, and went off as a man to fight in the war.”

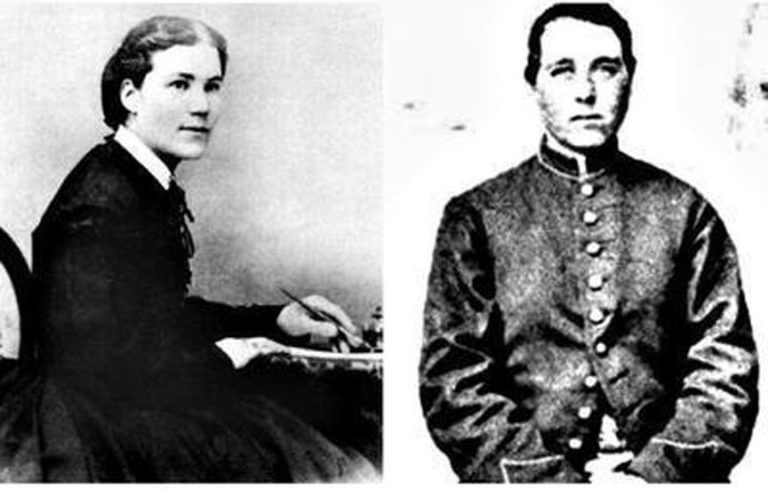

The coming of the Civil War challenged the Victorian society that had defined the lives of men and women in that era. In the North and in the South, the war forced women into public life in ways they could scarcely have imagined a generation before. Ruth was not alone. More than 400 women disguised themselves as men and fought in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. Sarah Edmonds Seelye, also known as Franklin Flint Thompson of the 2nd Michigan Infantry, said, “I could only thank god that I was free and could go forward and work, and I was not obliged to stay at home and weep.” Seely was the only woman to receive a veteran’s pension after the war.

Sarah Edmonds Seelye AKA Franklin Flint Thompson

Women stood a smaller chance of being discovered than one might think. Most of the people who fought in the war were “citizen soldiers” with no prior military training–men and women alike learned the ways of soldiering at the same pace. Prevailing Victorian sentiments compelled most soldiers to sleep clothed, bathe separately, and avoid public latrines. Heavy, ill-fitting clothing concealed body shape. The inability to grow a beard would usually be attributed to youth.

From the south, there was Janeta Velázquez. She was born in Cuba to a wealthy family, and at the age of 14, she eloped with an officer in the Texas army. When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, her husband joined the Confederate army, and she pleaded with him to allow her to join him.

Civil War map of Cuba 1865

Undeterred by her husband’s refusal, Velazquez had a uniform made and disguised herself as a man, taking the name Harry T. Buford and the self-awarded rank of lieutenant. She was just in time to fight at the Battle of First Manassas (Bull Run) and the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. Shortly afterward, she once again donned female attire and went to Washington, DC, where she was able to gather intelligence as a spy for the Confederacy.

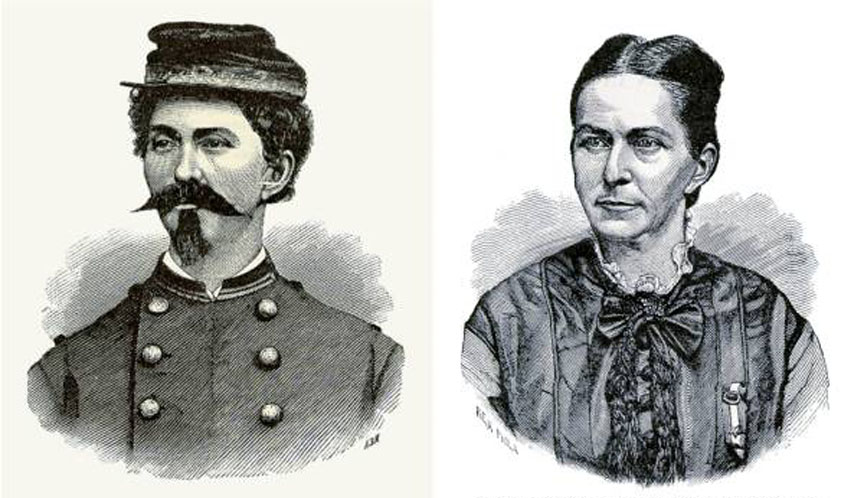

Lieutenant Harry Buford – aka Loreta Janeta Velázquez

Espionage did not hold enough excitement for Janeta, so she once again sought action on the battlefield. As luck would have it, she found her original regiment from Arkansas and fought with them at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862. While on burial detail, she was wounded in the side by an exploding shell, and an army doctor discovered her true gender. Janeta Velazquez decided at this point to end her career as Harry T. Buford, and she returned home to New Orleans.

Rachel told David that Ruth had a passion to fight as strong as the men did and even more, having witnessed the death of her, own husband, her childhood sweetheart, and her best friend. Her feelings were well known also to her sister Rachel through the letters they shared with each other as often as possible. Reading her words Rachel could feel the pain of her twin sister’s loss as if it was her own. Rachel also could feel what was in her own heart and how she felt about David. She wondered, did he even know she loved him, and how much she did?

While David was away, off marching to war, Rachel was trying to march right into his heart the best way she knew how, and that was to become best friends with his mother. This challenge was made super easy because David’s whole family loved the twin sisters, and his mother took Rachel under her wings. David had no idea what these two women had planned for both of them.

woman at work

The poor man was exhausted by the time they got him back to the farm. David had very little feelings left to express just how glad he was to be back home. When you are fighting daily just to stay alive, there is little room in your life for feelings. He just did not know how to express himself very well. That did not bother anyone because they had so much, they wanted to tell him all at once, and he so much was enjoying listening to their voices.

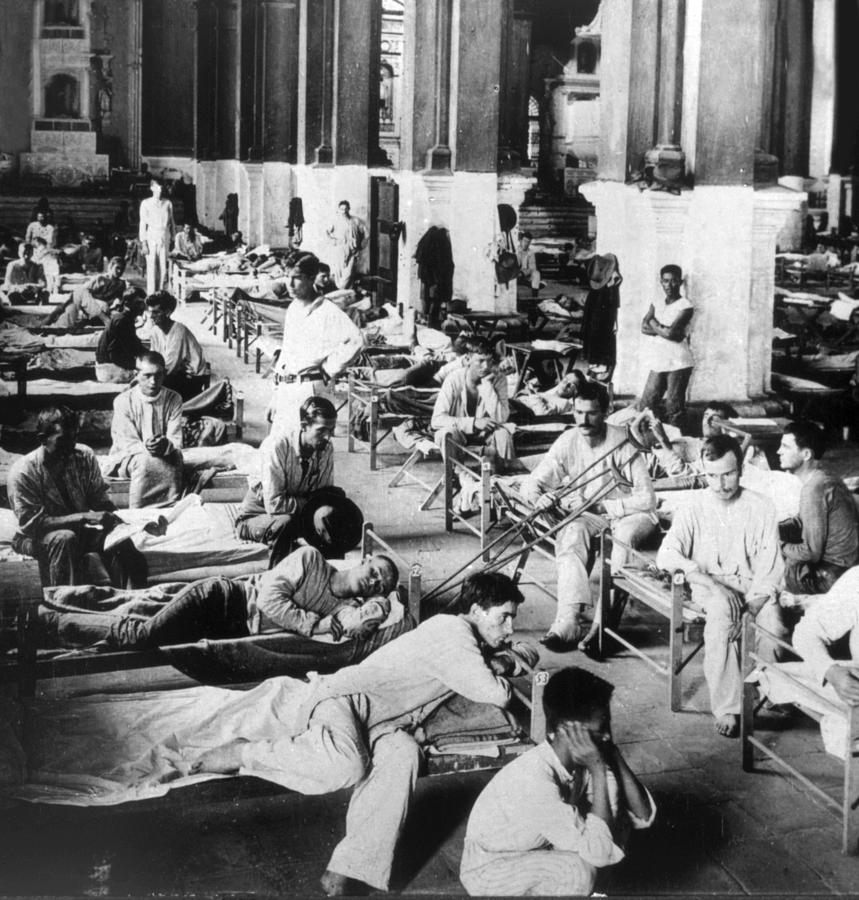

David was like most of the Civil War servicemen, they were farm boys, in their teens or early 20s. They rarely had, if ever, travelled far from their family and familiar surroundings. The combat that they lived thru was concentrated and personal. The disease killed twice as many men as combat. During long stretches in crowded and unsanitary camps, men were haunted by the prospect of agonizing and inglorious death away from the battlefield; diarrhea was among the most common killers.

Civil War hospital condition

The army was not always adequately outfitted, and some troops fought on foot. The armies faced each other in tight formation and firing at a relatively close range as they had done for years. They could see the expressions on the faces of their enemy. By the time of the Civil war, they were using new accurate and deadly rifles, as well as improved cannons on both sides. The men were often cut down in masses, showering the survivors with blood and body parts.

battle lines

These conditions contributed to what Civil War doctors called “nostalgia,” a centuries-old term for despair and homesickness so severe that soldiers became listless and emaciated and sometimes died. Military and medical officials recognized nostalgia as a serious “camp disease,” but generally blamed it on “feeble will,” “moral turpitude,” and inactivity in camp. Few sufferers were discharged or granted furloughs, and the recommended treatment was drilling and shaming of “nostalgic” soldiers—or, better yet, “the excitement of an active campaign,” meaning more combat.

a nostalgic soldier

The Civil War occurred in an era when modern psychiatric terms and understanding didn’t yet exist. Men who exhibited what today would be termed war-related anxieties were thought to have character flaws or underlying physical problems. For instance, constricted breath and palpitations—a condition called “soldier’s heart” was blamed on exertion or knapsack straps drawn too tightly across soldiers’ chests.

CRS, combat stress reaction was first called “divine madness” by the Greeks. Later during the Napoleonic Wars, it was called “nostalgia.” Then during the Civil War is was named “camp disease or soldier’s heart.” By the time of WW I doctors called it “battle fatigue or Shell Shock.”

The phrase, “the thousand-yard stare” was coined during the WW II and use thru the Vietnam war. It was a phrase often used to describe the blank, unfocused gaze of soldiers who have become emotionally detached from the horrors around them. It is a reaction to the intensity of the bombardment and fighting that produced a helplessness appearing variously as panic and being scared, or flight, an inability to reason, sleep, walk or talk. Military doctors from that time called this,” PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder.”

1000 yard stare

During the Civil war, wounded men who survived combat were subject to pre-modern medicine, including tens of thousands of amputations with unsterilized instruments. Contrary to stereotype, soldiers didn’t often bite on bullets as doctors sawed off arms and legs. Opiates were widely available and generously dispensed for pain and other ills, causing another problem: drug addiction.

early opiate-based medicines

David saw some men in his own company had a hard time after they got back home and no longer could rely on these medicines. During his time as a wounded soldier, no one had offered him anything for pain or support dealing with stress from combat. Like most of the men, he kept things close to the belt, and his feelings to himself.

Timeline 1867 – 1870

soldiers on the home front

David was almost home. He would sleep on the family farm tonight. David’s mother proudly told him that Rachel had been regularly going to the train station to meet the men coming home from the war. “She has been a soldier on the home front,” his mother said as she turned around in her seat and smiled at Rachel. Rachel and many women wanted to take a more active role in the war effort. Inspired by the work of Florence Nightingale and her fellow nurses, they tried to find a way to work on the front lines, caring for sick and injured soldiers and keeping the rest of the Union troops healthy and safe. Many other women fought that war on their own terms.

Confederate plan 1st Battle of Bull Run – 2nd Battle of Bull Run

Clara Barton was a civil war nurse who began her career at the Battle of Bull Run, after which she established an agency to distribute supplies to soldiers. Often working behind the lines, she aided wounded soldiers on both sides. After the war, she established the American Red Cross. Clara Barton said that the Civil War caused “fifty years in the advance of the normal position” of women.

Clara Barton with the 13th Mississippi infantry regiment

In June 1861, the federal government agreed to create “a preventive hygienic and sanitary service for the benefit of the army” called the United States Sanitary Commission. The Sanitary Commission’s primary objective was to combat preventable diseases and infections by improving conditions, particularly “bad cookery,” and bad hygiene in the army camps and hospitals. It also worked to provide relief to sick and wounded soldiers. By war’s end, the Sanitary Commission had contributed almost $15 million in supplies–the vast majority of which had been collected by women–to the Union Army.

United States Sanitary Commission

There are many soldier’s stories from the only war that America fought against Americans. The Union and Confederate soldier’s stories are the ones most told. But the other soldier’s accounts must also be remembered with equal importance and reverence. The women fought in many ways, but equally as dangerous battles, on different fronts. The black story is a scar upon our nation, that made us united and stronger, by the ones that endured that great pain. The Doctor’s story brings to reality the real horrors of war. All mankind should pray to God that we never have another one. The pastor’s story gives hope in times that seem hopeless. One more soldier’s story that has been overlooked too often is the children’s story.

Some children served in the army as soldiers, others just witnessed the horror of war from afar. Johnny Clem, at the age of 9, followed along with the 22nd Michigan regiment, and later, he was adopted as a drummer boy. Drummers were used for communication on the battlefield. Different drum rolls signalled various commands like “retreat” or “attack.” He became well known when he shot a Confederate officer and escaped at the battle of Chickamauga. He stayed in the army and after the war, he became a Brigadier General.

Johnny Clem

Children did not have it easy during this time. Some were with their families serving in the army. They help cook and wash dishes and set up and tear down camp when they moved. They were often near the front lines. Most children at home had a relative who was off fighting, and they had to work extra hard taking on the jobs of adults to help make ends meet. Much of the fighting took place in the South. These children could hear gunfire and artillery around their homes, and see the soldiers go marching by.

Confederate troops

David felt like a young child again, and he was thrilled to be back in his home community among his own people. His mind was flooded with childhood memories of playing in the woods with Chunky and all his cousins. He had many relatives living there, and indeed everybody made him feel glad to be home again. Here he got square meals and someone to dress his wounds. They even gave David two clean shirts for “one on, and one in the wash.” The one he was wearing had to be held together at the waist with twine.

Timeline 1871 – 1874

Lehigh county Pennsylvania

Then it hit him. No one had mentioned anything about Chunky. When he inquired as to his “whereabouts,” all anybody could tell him was that he had not been heard from after the battle of Gettysburg. Not one member of his family had any idea what had happened to him. All the men from the regiment were met with a royal welcome from the good people of that county. They gave them an elegant dinner at the Fair Grounds, where beautiful girls waited on the tables.

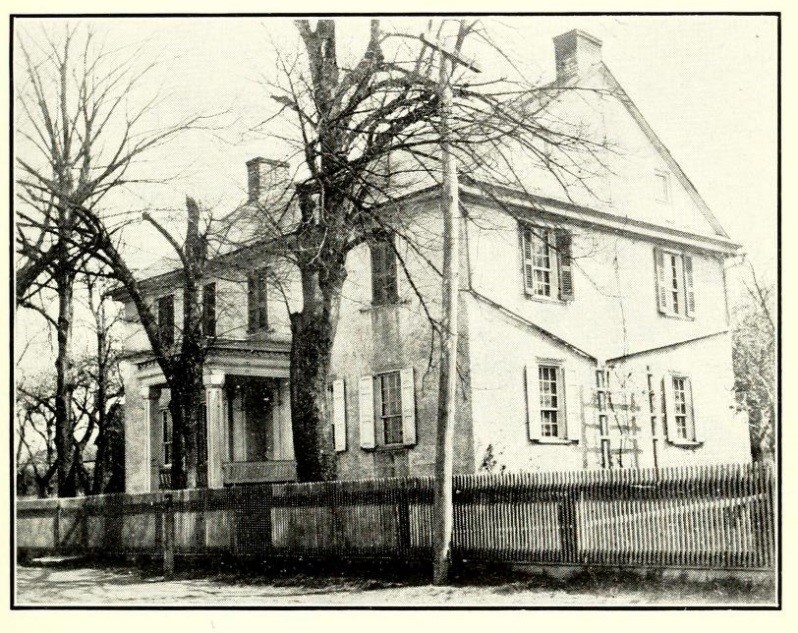

Knauss ancestral homestead, 1802 Emaus, Pa.

many of the Knauss were born here

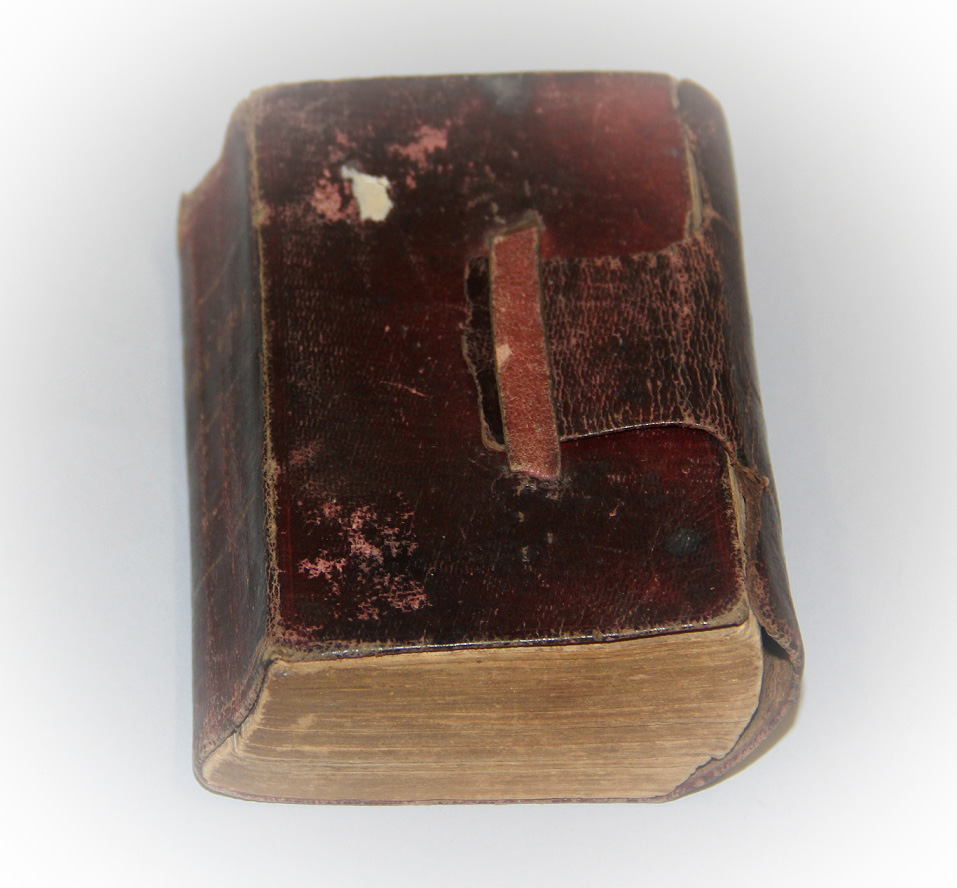

When David went to the army, he took for his guide a Bible. One of his favourite selection was from the 91st Psalm.

“Whoever dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, he is my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

He had lost the Bible he used to keep his diary safe, somewhere during the battle of Gettysburg. He wished he could reread his own writings.

Gettysburg Headquarters General Meade

Timeline 1867 – 1883

Timeline 1875 – 1876

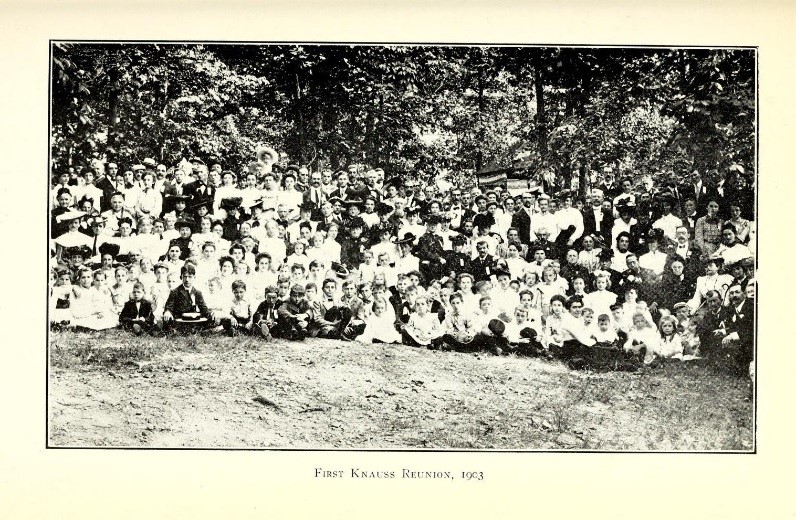

As David grew older, there were many times his heart was saddened that he was no longer in possession of his testimony to history, his diary. He had hoped to share with his kin and future family his war experiences, but now all he had was distant memories. And as he grew older, still these slowly faded from his memory. Thirty years later, at a Knauss family reunion, David had this to say to the people that gathered to celebrate that day.

June 6, 1909

“I was in some hard marches. On one of them were only enough men left in our company (d) to make three rifle stacks. The rest had all given out on account of the excessive heat and were left behind. I was in two hard battles: Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. At the former we left our knapsacks before going into battle and never recovered them. There came on a cold rain, and we were ordered not to speak above a whisper until we got back across the pontoon bridge (at u. S. Ford). The night was cold, and we had a hard time of it. I found a wet blanket and went into timber and built a fire to dry the blanket. At the time we started to Chancellorsville we had eight days rations dealt out to us. I divided mine so as to get through with it pretty well, but others who ate all they wanted, ran out of provisions and got so hungry they took corn from the horses’ troughs and parched it.

The first day at Gettysburg it seemed to me the rebels were bound to get to town. They shot a hole through the lines where we were, and our company was badly broken. When on the retreat, I kept loading and firing back on my own account. I was called in a few times to help take care of the wounded, and did the best I could, but would not give up my rifle. I then turned the wounded man (whom I was assisting) over to another fellow. Soon after this the hospital and all its inmates were captured. I picked up a better gun on the field. We were engaged at sharpshooting, under heavy shelling the rest of the day. At night, the enemy came up and drove us back to our battle line, where they got the worst of it and were defeated that night. We had no officers left in our company, and the next morning the few men remaining of co. D were put in another company, the combined force numbering 22 men.”

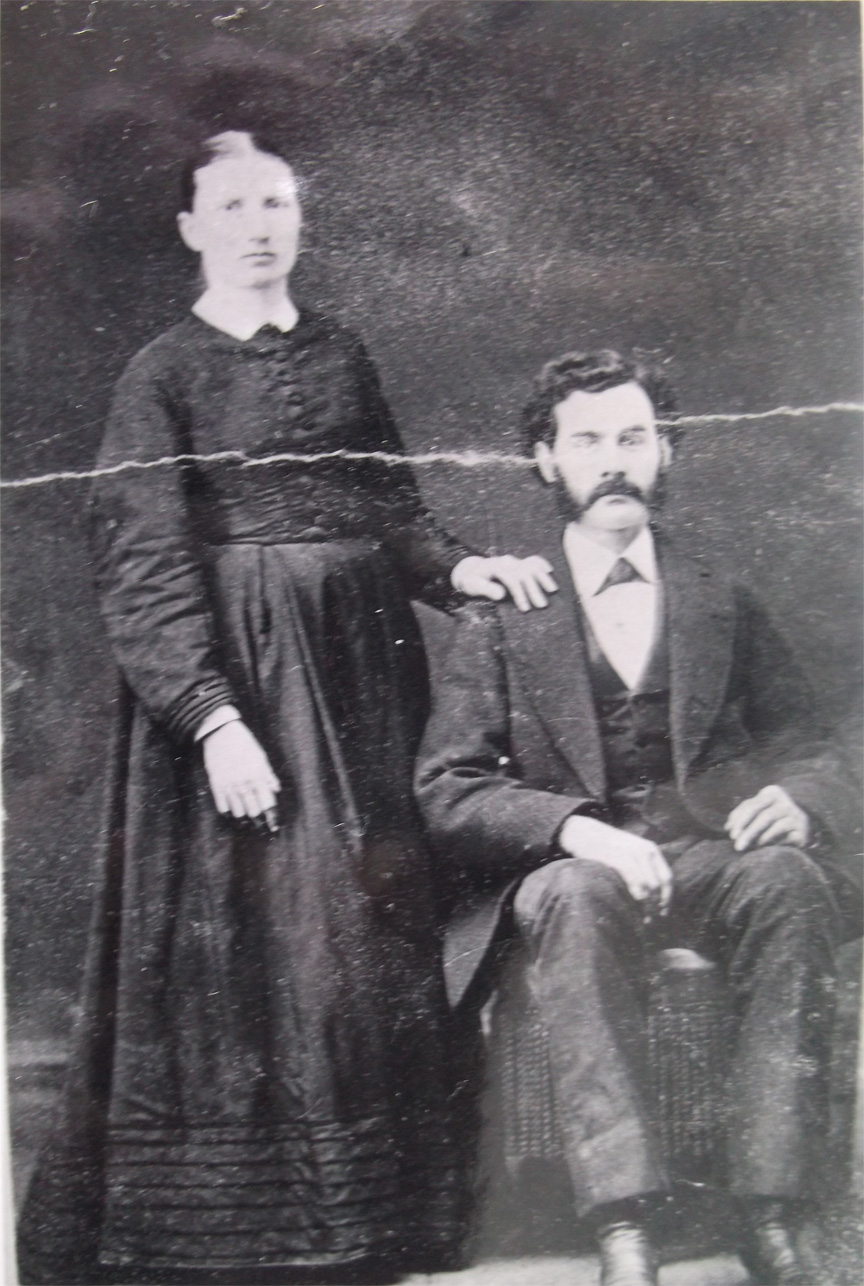

Mr. & Mrs. David Knauss

Sound Bite 1878 – 1882

Sound Bite Native American

David had received a letter in August the year before, from one of his cousins saying that they had attended a family reunion of 600 persons. At that meeting, they had the Bible, which he had lost in the army. A reformed minister of Tom’s Brook, VA, saw in the local newspaper notice of the intended Knauss family reunion. He had at the time, in his possession, a Bible with David’s name in it. The minister told them that fourteen years earlier, he was stationed in South Carolina, when one of his parishioners who had been a Confederate soldier, gave him the Bible. The book contained the name, “David Knauss Army of the Potomac, born in Northampton Co. Pa, son of Levi Knauss Exq.” It also had the Apostle’s Creed written in German

Knauss family reunion

It was the high point of the family reunion that day when the family presented a young man’s Bible back to its owner, the old soldier. David watched as they brought it towards him. His mother’s quilt scarf that he had kept it wrapped in was missing, but he remembered he had used it as a bandage for his wounded leg. Even with his aged vision, he could see, from a distance, that the Bible was his old friend. He could recognize the book from the outward bulge in the cover made from the diary he had kept inside it. As he looked at it, he wondered if he looked as old and worn-out as this book did. He held it tight to his breast and said a silent prayer of thanks.

Civil War bible

There were so many people to thank, and David had such a good time that day, that it was not until the next day he took time to open the Bible. But the bulge in the book was only an indentation of what used to be held there. He could see the outline of his diary on the outside cover. But the space inside where the journal was kept was empty. It was not there. The old soldier felt that it was much better to remember and pass on the words of the Lord that he just got back, rather than the thoughts of man. David was very grateful to have survived as long as his Bible had.

Next: The trees of Michigan

>>>Click here <<<

Word count: 6256