David Knauss, Co. D, 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteers

Timeline 1844 – 1866

Timeline 1825 – 1849

“The reason you can run so fast is your legs are shorter, and you are closer to the ground,” Chunky told his best friend, David, one day.

David was small in stature, but he often defended himself, stating, “I’m tall! It is just that everyone else is taller.”

From the time he was in grade school, no one messed with David, or his best friend, Chunky. When the two boys wrestled, and if David had fought really hard, sometimes Chunky would let him win, but not always. When it came to running however, no one could keep up with David. Together the boys made fond childhood memories of playing in the barn, hiding in the hay, building forts in the big piles of animal feed.

Soon after David Knauss was born, his father, Levi Knauss, bought some land in Northampton County, Pennsylvania. There he spent his boyhood days on the family farm. Farmland was being sold in 80 acres plots, and it was good bottomland.

Early Northampton County

Levi and a neighbor, Jonah Godfreed, bought one plot together and broke it up into two farms. David grew up with Jonah’s only son. Since he was a huge baby when he was born, his father gave him the name Chunky.

David’s uncle owned another 80-acre plot next to his father’s farm. So, David and Chunky spent a lot of time playing together with all the cousins of both families. The families were very large, and parents, several children, aunts, uncles, and a grandparent or two, lived under one roof. The close-knit family ties gave all the young people in the neighborhood a certain sense of security.

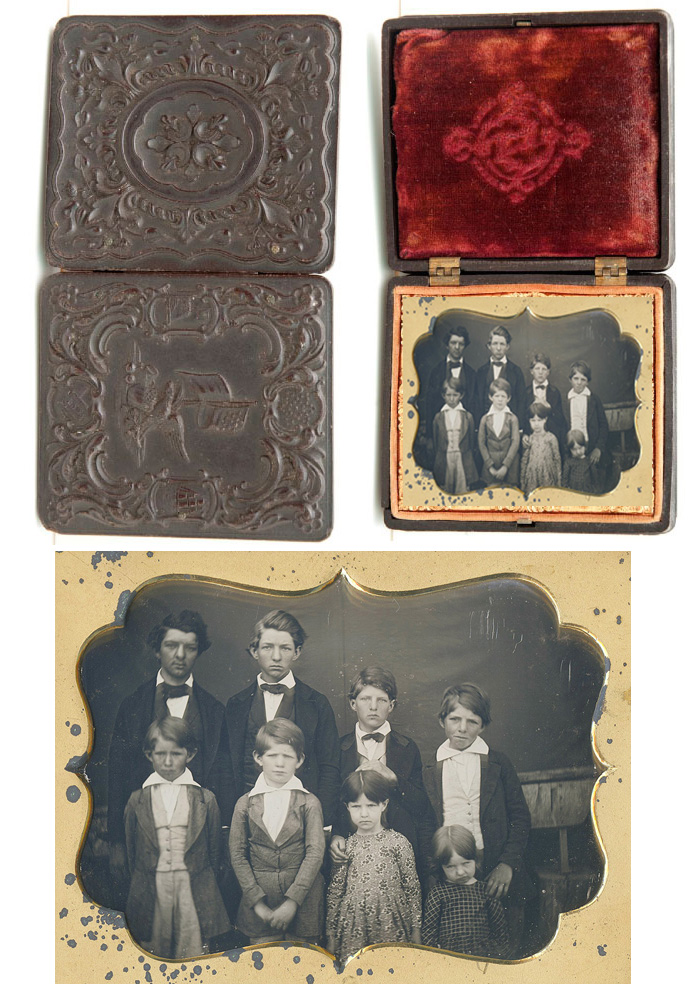

The families always got together for holidays and shared the meal. The adults gathered at the adult table, and the kids got their table in another room. One year, when they were outside celebrating the Fourth of July with a big barbecue, a traveling photographer stopped on his way to town. He got all the children together and took a picture, and for 25 cents, each child got a small tintype.

A tintype

A tintype was made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel. One or more hardy, lightweight, thin tintypes could be carried conveniently in a jacket pocket. They became very popular in the United States during the American Civil War.

Although the two boys were the same age, Chunky was one month older than David, and they argued about that all the time. They received their education in the Township Schools and in the woods of Northampton County. Running through the thickets and tall trees, the boys became closer to God’s creation. They learned about Him on Sunday, and the rest of the week felt His presence under the trees.

The entire 80 acres were as well-known to them as each other’s face. They learned how to hunt and fish and survive in the forest. Together, they found the best trout fishing holes in the stream that separated their two properties. The wild game was plentiful, and the fishing was always good. They gathered mushrooms in the spring, as well as acorns for making Chicory (chic-o-ree) in the fall and traded them in town.

In times of coffee shortage or an economic crisis like the Civil War, Chicory root or Acorns were ground up and added to the coffee to stretch out the supply. Parsnips were also added occasionally. Even burnt sugar was sold to coffee dealers and coffee-house keepers under the name of “blackjack.”

This was a rural farming community, and all the children in the neighborhood went to the same one-room schoolhouse. David and Chunky had many friends from families of different backgrounds. The Indian children from the Delaware tribe that went to the school were younger than David. Still, the boys taught them many things about surviving alone in the woods. The older boys loved to listen to the younger ones tell stories about their families’ life-experiences as Native Americans.

The Delaware Indians were originally known as the Lenape (le-nape), or Lenni Lenape (leny-le-nape), Indians, the name they called themselves. The American colonists named them the Delaware Indians because their original homelands were along that river.

Lenape Indian hunting grounds purchases by colonists 1682 – 1874

These young braves were from different clans called Pele (pee-lee), the turkey, Tukwis-t (to-ca-wis-ta) the wolf, and Pukuwanku (pu-ku-wan-ku) the turtle. They all had one thing up, on David and the other kids: They could speak in more than one tribal language, and pretty good English to boot. They were held in high favour among the other students in school. Later, these clans would be removed to Oklahoma.

The Treaty of Shackamaxon with the Indians, otherwise known as William Penn’s Treaty or “Great Treaty,” is Pennsylvania’s most longstanding historical tradition. According to the legend, soon after William Penn (1644-1718) arrived in Pennsylvania in late October 1682, he met with Lenni Lenape Indians in the riverside town of Shackamaxon (sack-a-max-on) present-day Fishtown. And there, beneath a majestic elm, they exchanged promises of everlasting friendship.

In 1857, Granville John Penn donated to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania a belt of wampum (shell beads) depicting two men joining hands; the Lenapes had purportedly presented it to his great grandfather at the signing of the Treaty.

All the children played together outside, except when the boys wanted to play war. Then the girls had no problem keeping busy doing more exciting girl things. They would playhouse with their doll and pretend to be a mother or have a tea party. Girls liked to read books and notes from each other. At church, the girls gathered in a circle and usually were left unattended. The teachers spent more time with the boys because the girls were better behaved. They love to gossip about the boys when they got into trouble and what “so and so said.” Girls love to have sleepovers whenever they could. Girls spent a great deal of time whispering and giggling and passing notes.

Two girls stood out among the other young ladies that attended the local school and church. Rachel and Ruth were twin sisters that made you see double. They looked so much alike that they often traded names, so they could confuse any person trying to talk to them. Once when they were just newborns getting their first bath, their mother suddenly realized that she did not know which one was which.

There was a small freckle in the eyebrow of one of the babies, so she decided, “this one shall be Rachel because I will never tell that I got them mixed up.” Their mother never told the girls how she could tell them apart, but she could, and they always wondered how.

Whenever the girls wanted to play together without the boys in the way, they would say, “let’s ask Rachel and Ruth what they want to do now.”

Young girls in those days, in some areas rarely attended school, homemaking was a full-time job. What they would mostly do during their free time is sewed, do needlework, and visited one another. Women and girls would spend much of their time writing letters. Because paper was difficult to obtain at the time, the girls wrote on birch tree bark, in the sand, and on the ice and snow. They used the leaves of the trees and scrap strips of leather for their manuscripts.

In Northampton County, all the children went to school together, boys and girls. Classes would be held sometimes, due to the season, either inside or out. Each child had a small black chalkboard to work out and complete the lessons. Good penmanship was always a requirement. All the girls loved to practice their handwriting, and they felt lucky when they got a piece of paper to do it on.

Platt Rogers Spencer designed the Spencerian method of cursive handwriting. He is known as the “Father of American Penmanship.” His writing system was first published in 1848, in his book Spencer and Rice’s System of Business and Ladies’ Penmanship. The girls would compare each other’s work to see which letters they still needed work on. They took great pride in their penmanship ability and teased the boys about it.

The history of writing

When they had time away from learning about homemaking, the girls played games. The game of Graces was performed by two players, either two girls or a girl and a boy. Boys did not play Graces with one another because it was considered a “girl’s game.” The game involved whirling a coloured hoop toward your partner, who attempted to catch the hoop on the tip of a slender wand. This classic game was considered to offer young ladies both proper and correct exercise.

One game the girls did play with the boys was Jackstraws or Pick-up-sticks. The Indian children at the school taught them to play it with straws of wheat. To play, all that was needed was a pile of wood splinters or straws. The sticks were heaped in the middle of a table. Each player took a turn removing one stick from the pile. The challenge was to do so without moving any of the other sticks.

Playing dominoes was a favourite pastime in the late 1800s. This game was played by the young and old. Dominoes are flat, rectangular blocks called tiles or bones. Each tile has two groups of dots on one side. The dots range in number from zero to six. The tiles are put in the middle of the table, face down. The first player to lay down all of his or her dominoes, by matching up the numbers, wins.

Rachel and Ruth were inseparable when they were young, but as they grew older, Ruth got into more outdoor things like the boys were into. She loved to go hunting, not so much for the thrill of the kill, but she liked the freedom being out in the woods. She had no problem slipping on boy’s pants to keep warm when she went hunting with them during the winter months. She was a deadly shot with her father’s rifle, and she bagged her first big buck at the age of 13. The boys with her that day were amazed that Ruth insisted on field-dressing out her deer. After that, Ruth always had a well-deserved and very proud memory of that day.

Rachel loved to read, and she devoured anything in print. She used to keep all the newspapers she could get her hands on, so she could read the stories again and again. She cut out the stories that sparked her interest and kept them tucked neatly between the pages of a book.

She loved to read the published letters of Florence Nightingale about her experiences as a nurse in the Crimean War from 1854 to 1856. Nightingale was a prodigious and versatile writer, who was concerned with spreading medical knowledge. She wrote her tracts in simple English, so they could easily be understood by those with poor literacy skills.

Timeline 1850 – 1858

Florence Nightingale, at the age of 24, and coming from a wealthy Italian family, felt called by God to help the poor and sick. She is considered the founder of modern nursing. She was known as “the lady with the lamp.” And she and her nurses saved many lives during the Crimean War.

Rachel read about how she took notice of the dirtiness and deterioration of the military hospitals. The conditions in the hospitals were dreadful, and wounded men were sleeping in overcrowded, dirty rooms without any blankets. Wounded soldiers often arrived with diseases like typhus, cholera, and dysentery. She saw that more men died from these diseases than from their injuries. Often, the soldiers were not even given food and medicine to help them get better.

The army doctors did not want the nurses helping. Soon after they arrived, however, there was a huge battle, and the doctors realized they needed help. Florence Nightingale knew that if the doctors were going to allow her nurses to work, they must be excellent at their jobs.

Rachel fully embraced the Nightingale effect, where a caregiver would develop a romantic feeling for a patient, even if very little communication or contact took place aside from basic care. She believed that feelings would fade once the patient was no longer in need of attention. The two sisters, Rachel and Ruth, enjoyed a lifetime close relationship. Whenever they were apart, they always communicated daily with a short letter.

For the boys, playing war was fun. You could shoot at anything by just using your forefinger of either hand. Your guns never ran out of ammunition or bullets. And if you made a good “bang” sound, it was quite a believable hand toy. But the best part of playing war was playing dead. You were judged by the other boys on how good an actor you were. An even better part of the game was that you could get up after being killed and keep on playing war again and again with the same results. Nobody really died. It was just a fun game.

Sometimes though, things got a little rough out there in the brush. One time, one of David’s cousins was using a stick like a rifle, and as he was running, the stick became lodged between two trees and broke. The broken piece struck the boy on the right side of his face. It gave him quite a cut that later left a small but a deep scar.

This young lad did not complain; he brushed it off by saying, “I drew first blood,” and along with the other boys, they all had a great laugh.

Jonah Godfreed, Chunky’s father, ran a brewery on his farm. He grew grain, hops, and all the things he needed to make beer that the local German people drank. Previously, beer had been brewed at home, but the production was now successfully replaced by medium-sized operations like Jonah Godfreed’s, with about eight to ten workers. Jonah Godfreed’s beer was brewed the old German family way, which he kept a secret to himself.

Beer, one of the most common drinks, was consumed daily by all social classes where grape cultivation was difficult or impossible. Though wine of varying qualities was the most common drink in the South, beer was still prevalent in the North. Beer became vital to everyone in the grain-growing community.

David worked with Chunky at the brewery, and at one time, they talked about starting out on their own making beer. These two young men could provide for their families at an early age, and they often did so.

Timeline 1860 – 1864

The war trumpet heralded the outbreak of the Civil War in the Autumn of 1862, calling for recruits to strengthen the Union forces. Robert E. Lee’s army threatened a northern invasion, and more men were needed to repulse the enemy. Northampton County, instead of a draft, raised a full regiment of volunteers. Like many young men at that time, David’s first thought was the duty to his country. Even though his father and mother did not approve, David entered the service.

David and Chunky rode together on the same mule, named Henry, on the way to enlist. When they got there, all they had to do was turn him loose and swat him on the butt, then shout, “Henry, home” and the mule would find his way back to the barn. David and Chunky enlisted together in Company D.

David was an avid reader, and he would devour any books he saw. His penmanship was impeccable, and he also mastered numbers.

The officers were aware of David’s skills, and he was, therefore, quickly assigned to the position of company clerk. He did not enjoy sitting at a desk doing paperwork, preferring to be outside, but David was a great help to the men who could not read or write. He would read them their mail and help them write letters to send back home.

David kept a journal of his personal experiences and of the men around him. He kept it tucked inside the cover of his Bible in his haversack (a small, sturdy bag carried on the back or over the shoulder, used mainly by soldiers). One day, he opened the diary to the first page and made his first entry.

No date:

First, I think of the home-leaving. The sad thoughts of separating from dear ones and the comforts of home. To engage in the turmoil of war—for which I have no taste whatever. Why did I, with others, decide to enlist and join the 153rd regiment? It was in response to the call of my country in her great struggle. That call was stronger than the ties which bind us to our loved ones. We spent a few days in Easton, our county seat, where we received our first military training. We were then moved on to Harrisburg and quartered in camp Curtin. One of my most distinct recollections is that I was glad to get away from the place, though it meant going to scenes of active service. The sudden transition from home life to the camp life had a deleterious effect upon my health; it was not long until I could relish the soldiers’ diet; even a piece of bacon scorched over a hasty fire on the march. The boys had concluded that comrade Moore would get us about as near to the front as he could. My reply to them was, “boys, if you keep up with me from now on, you will do well,” and my prediction proved quite correct.

Chunky was very musically gifted from an early age. His voice could always be recognized in church, singing the different parts of the choir. He loved to play the guitar, but strings were hard to get. He found it was easy to carry a drum, so he made his own and always had one or two with him. He could sight-read music very well and later would often be called upon to lead the company band. Writing poems and putting them to music with the guitar was his favourite pastime.

But Chunky had a definite plan of action, and he had a very mature attitude about his future. Joining the army would be his steppingstone from the farm to the medical corps, then on to medical school. He had already proven his scholastic abilities by being at the head of his class each year. Chunky was very humble about his skills and always made his peers feel celebrated. Everyone that met him got an excellent first impression.

At the time of the organization of the 153rd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers Infantry, David Knauss was 21 years old. Most of the regiment’s officers and enlisted men were close friends or neighbors. Raised to war fever by the attack on Fort Sumter, he was among the first to respond to his country’s call.

To him belongs the honour of being one of the first who rendered his services to the government and was accepted. His inborn military spirit and patriotic impulses prompted him to respond to President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 men in the year 1861. This noble act gained him the esteem and well-placed confidence of the other men that he had encouraged to seek early enlistment.

No date:

I was ready when the war broke out, but, my parents refusing their consent to my enlistment, I went over to Kaston and went to work on the Lehigh valley railroad, and when the 153rd was being made up I stole myself away from my parents and enlisted in company d. I do not know who wrote to my family about this, but when it was time for us to leave, my mother was there to see us off. She gave me a new hand knitted scarf, a copy of the family tintype, and a kiss on the cheek. I keep the tintype in my shirt pocket at all times.

David closed the diary and placed it in the front cover of his Bible. Then he very ceremoniously wrapped the books in the scarf that his mother had given him. He could still smell her scent on the handmade cloth as he placed it in his haversack.

The examining surgeon and mustering officer tried to run some of the men in as substitutes. With the Enrolment Act, the Civil War truly began to be known as “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight” throughout the entire nation. It was possible, with enough money, to hire someone to take your place in the draft: a “substitute soldier.”

The $300 commutation fee was an enormous sum of money for most city laborers or rural farmers. And the cost of hiring a substitute was even higher, often reaching $1000 or more.

When David refused to do so, they offered him $1100. David told them, “there is not enough money in the State of Pennsylvania to hire me as a substitute soldier for another man.”

The Battle of Chancellorsville, fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863

Chunky and David were conspicuous in the two battles – Chancellorsville and Gettysburg – and in both these significant conflicts, they were entitled to great credit for their soldierly conduct.

By the time the regiment passed Washington and reached the camp on Virginia soil, the devastation of war had become real. And some of the boys began to realize that entering the army was not going to be a picnic. They began to learn that privations were a part of a soldier’s life and to think of the good things they had left behind at home. The cloudy water of this place did not compare with the limpid streams of old Mt. Bethel’s hillsides, and the pure water which bubbles up from the base of the blue mountain in sight of their home. They missed the cakes and pies of their mothers’ tables.

One of the boys was heard to say, “Oh! If I only could get home to get a drink out of our old spring!” But they were told to be courageous, for they had enlisted in a cause of good and could afford to undergo self-denial.

No date:

The Blue Mountain boys were as worthy in soldierly qualities as the ‘Green Mountain boys’ of revolutionary fame. From close and constant relations with these men of my company during the ten months we were together, I can say they were men that could be relied upon for the doing of faithful duties whenever called upon. When our regiment reached Alexandria, we were shown the building in which the young and gallant colonel Ellsworth was shot while descending the stairs from the roof where he had replaced the national flag, which had been pulled down.

After the winter of ’62 and ’63, the spring gave indications of active service all along the lines of battle. The entire army of the Potomac, then encamped on the north bank of the Rappahannock (rap-pa-han-noc) River, was ordered to be in readiness for an aggressive movement. On the morning of the 27th of April 1863, the advance began. The army moved in three columns, crossing in different places. General Hooker’s plans for getting his army across the river were well-made and accomplished. Having his forces now just where he wanted them and the positions and other conditions satisfactory, he was much elated. His address to the men was the occasion of great enthusiasm all along the line.

How successful his plans were, remained to be told? At this time, it was confidently expected that by the movements then going on, all railway communications between General Lee and his base of supplies would be severed. The Army of the Potomac was now supposed to be in such a position that there was nothing to prevent it from moving successfully on the enemy.

Next: The diary and memories of a Civil War soldier – part 2

>>>Click here <<<

Word count: 3982