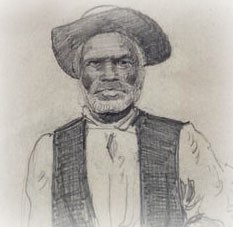

“Now I tell you when slavery…” he paused long enough to reach inside his shirt for some more tobacco, “…way back in slavery time, I was a good size boy then. That’s when me young.”

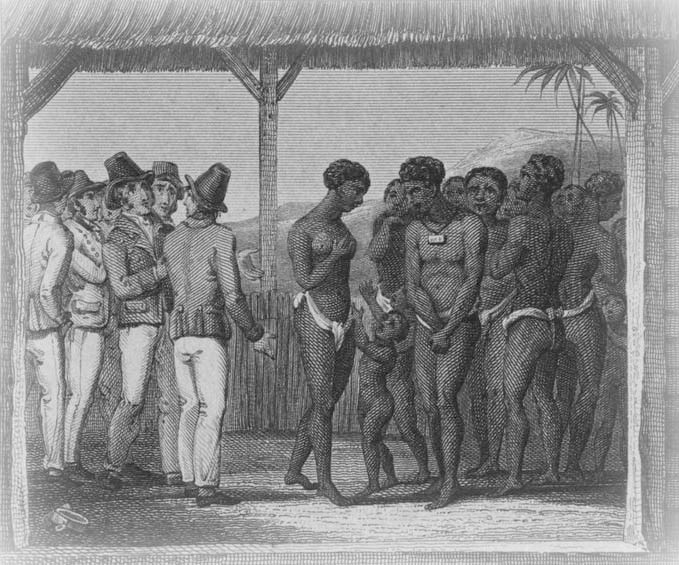

Jonah stretched out his arm and held his hand so high, then raised it a little. “Well my old master, he bought one, two horses, and Jonah. Now he took us all down to da farm, I recollect all of that. I was a big, big boy then. A good big boy. I’s remember my old master place. I’s remember he was a speculator. I’s remembers it, me was good big boy then.”

Then he stopped and gave great care to his corn cob pipe as he emptied and loaded it with fresh weed. The pipe and he were great friends, and they gave each other comfort and conversation when nobody else was around. They now held a captive audience that eagerly waited for what he had to say next.

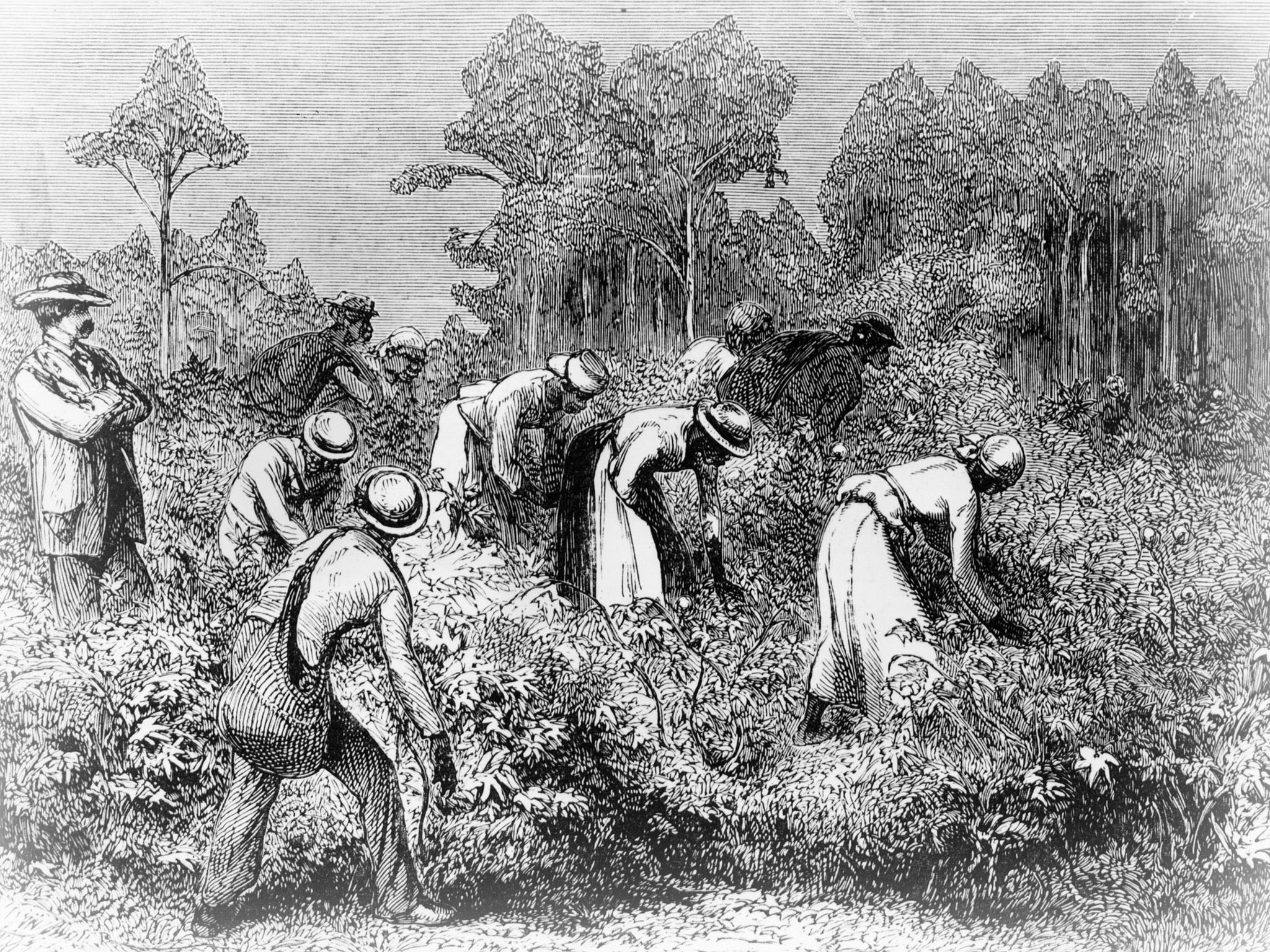

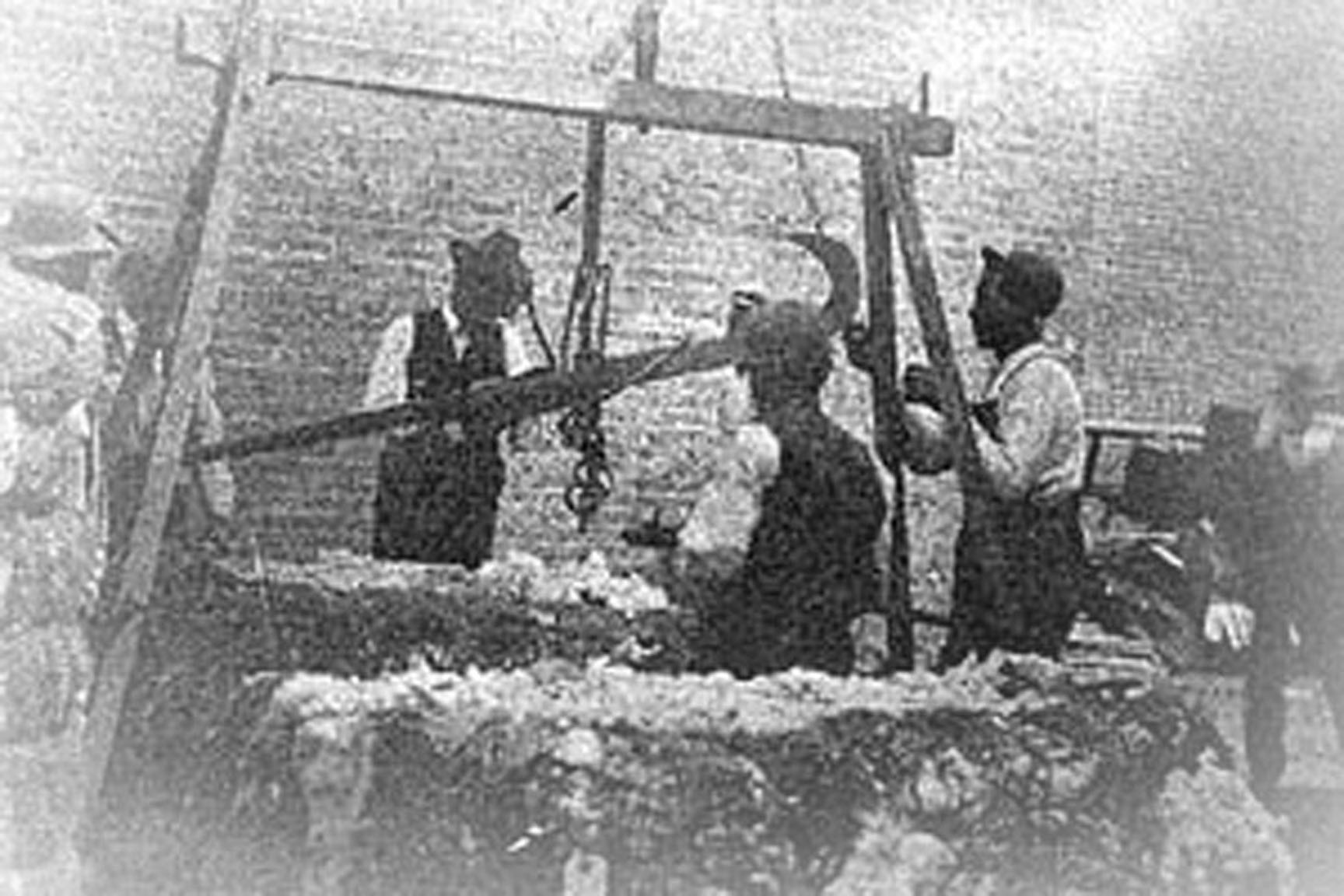

“He had a big old shed, dar. And he, and he had cotton all in that shed, and we boys would all go up and play in that shed every day.” Jonah could see that they were quietly listening to him with great respect for the story he was telling.

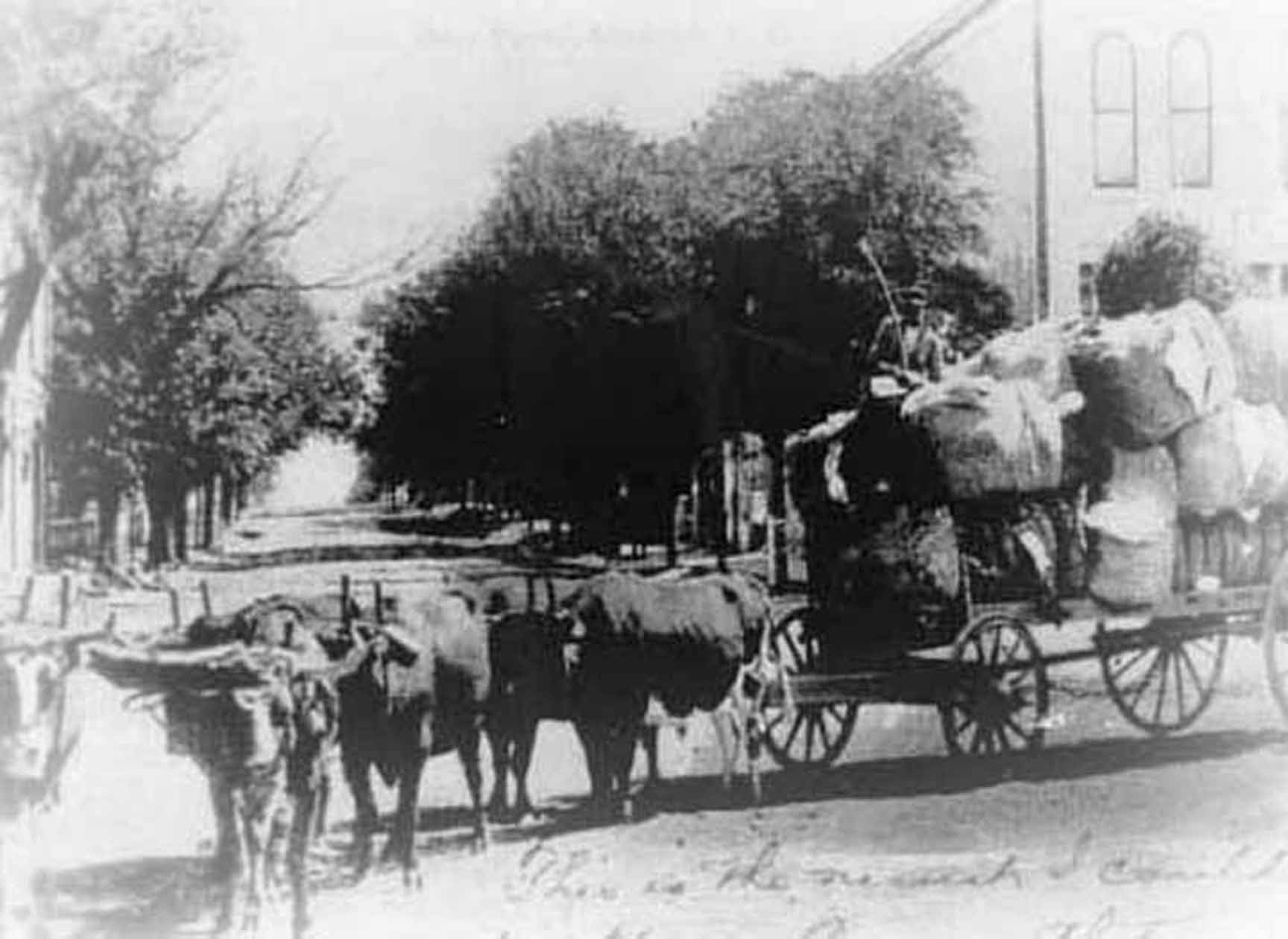

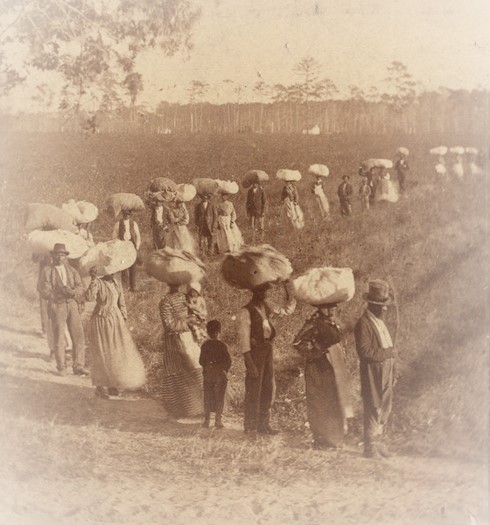

“And he had wagon, every, everyday he’d load up all them wagon and take all that cotton and go off, go off far. Now you see, that, that was in slavery time. I recollect just as well, and he’d bring back whole lot the colored people. The overseer, Black Adam say, master was speculator. And he sell them to all these people round this country. Him name just Adam, but we calls him Black Adam cuse he mean to other colored folks.”

Jonah wiggled his southern end on his seat as to resemble movement. “I recall that my old, my old papa was his wagoner.” He pretended to grab the reins and drive the wagon. He even made a snap sound as he showed how the whip was used.

“I used to go, he used to carry me with him all the time. Used to haul cotton, carry cotton in that wagon.” He tried to take a puff, it was out, so he relit it. And took a big spit. “They’d carry cotton over here and weigh it up at a place they call uh, forgot that place name now. Carry cotton there and weigh it. I’s remember he used to be, he used to always work.”

Flexing his muscles to get a laugh from his sober audience, he proudly proclaimed, “I was good, big boy at the time, and master had a oxen, had a old, had a oxen, had a old oxen name Steamboat. That how come papa was his wagoner. And I’d ride old Steamboat, ride old Steamboat, drive the rest of them. My britches soaked with Steamboat sweating on me. Ride him, till I get tired and get down, then walk side of them.”

“Well, old Steamboat get tired, and just set down. Overseer Black Adam says, get that whip, get on that, get this whip and get on it. As soon as Steamboat heard that whip he gave out a big snort from the rear end and started off on his own in the direction of the barn with wagon, cotton, papa.”

Jonah found someplace, especially deep in his heart, and come up with a belly shaker of a laugh that was contagious to everyone. It continued until it was apparent Jonah was out of breath. Then again, very quietly, he said, “Papa die when I’s young.”

The fire snapped a spark of life, and he watched the ambers float up to the heavens. “That, that was in slavery time, that was old slavery time, it was. And I remembers. I can tell you some more bout slavery time.”

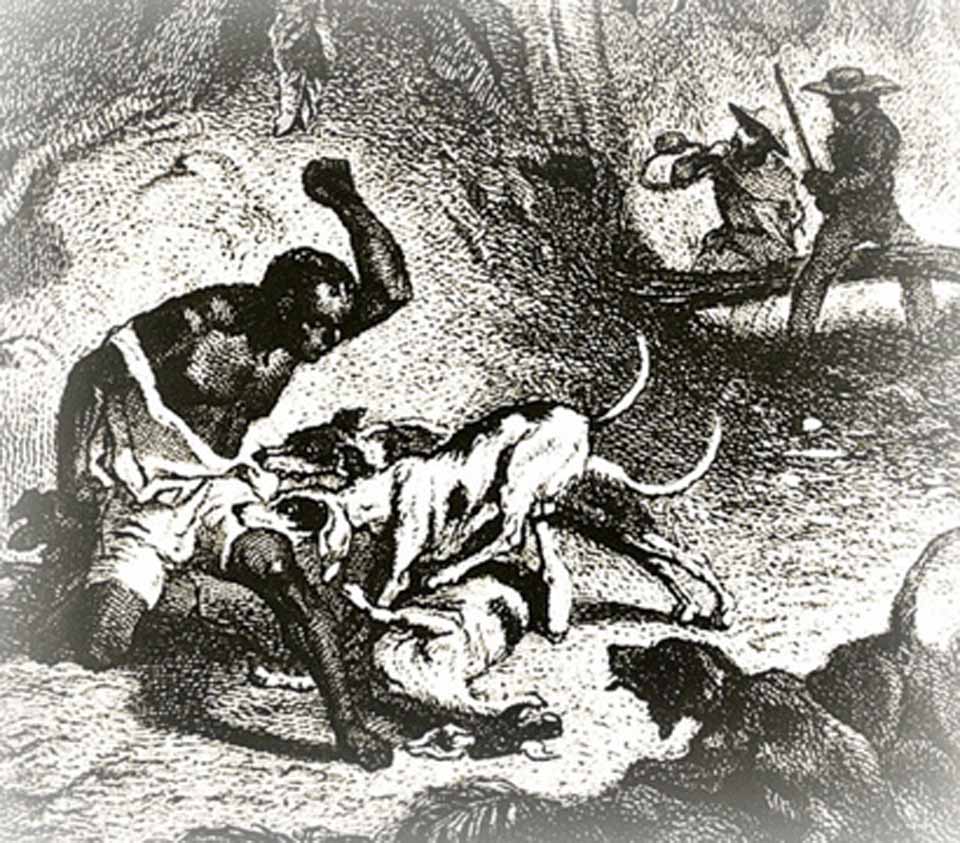

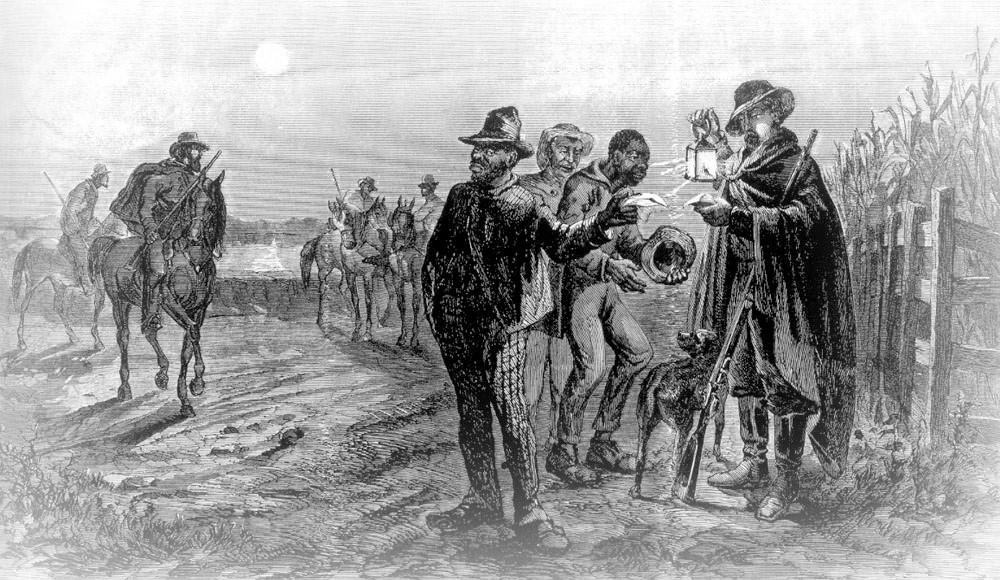

The children used one word to give their approval of the oral history lesson. They all responded as if they were in church together, with a moan of, “More.” After relighting the pipe but not taking a toke, Jonah smiled, showing he had no teeth left. He said, “And was an old log jailhouse. And all around I recollect one time, we all was looking at it. And they, and they brought in, had hounds. And they brought them hound in and brought three colored with them hound, runaway colored, you know, caught in the wood.”

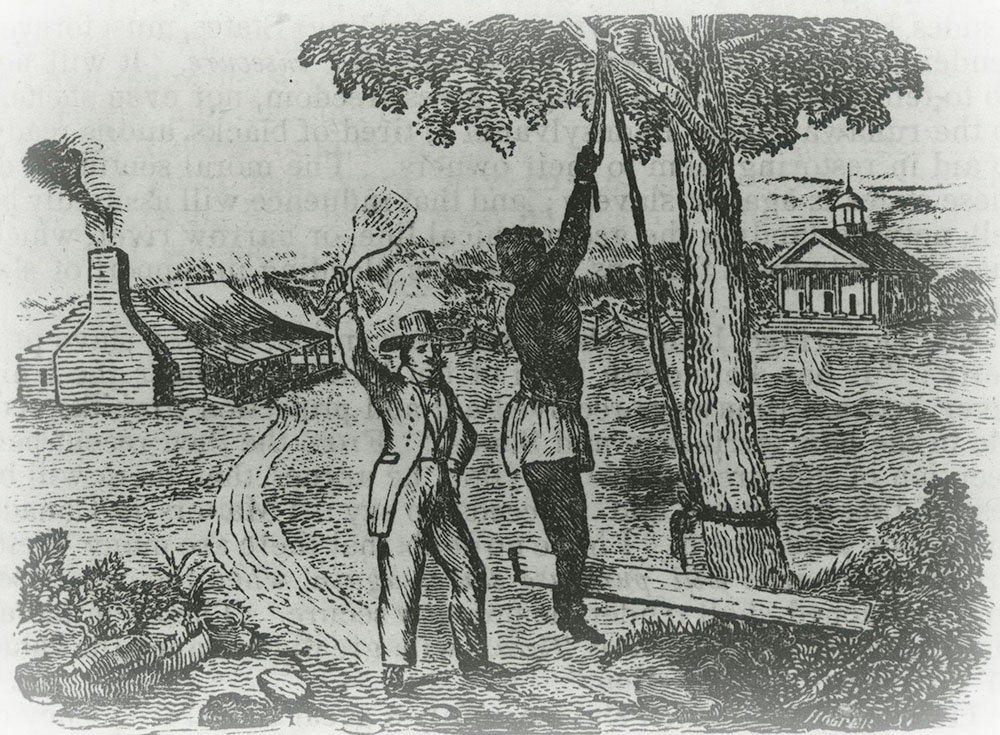

After taking a hit off his pipe Jonah continued, “And they, right, right across, right at the creek there, they take them colored and put them on, and put them on a log lay them down and fasten them. And whup em. You hear them boys hollering and praying on them logs. And there was a colored whup them. He gets whup his self if not do bad enough. Then they take them out down there and put them in jail. No one, no tell, what take place with them colored after. I don’t know, to tell you the truth when I think of it today, I don’t know how I’m living. None, none of the rest of them that I know of is living. I’m the oldest one that I know that’s living.”

Jonah glanced up at the night sky and said, “But, still, I’m thankful to the Lord. Now, if, uh, if the overseer wanted send me, he never say, you could get a horse and ride. You walk, you know, you walk. And you be barefooted and collapse. That didn’t make no difference. You wasn’t no more than a dog to some of them in them days. You wasn’t treated as good as they treat dogs now. But still I didn’t like to talk about it. Because it makes, makes people feel bad you know. Uh, I, I could say a whole lot I don’t like to say. And I won’t say a whole lot more.”

The silence of the audience was interrupted by a question from Chunky, “Well, was your father a songster like you, papa?”

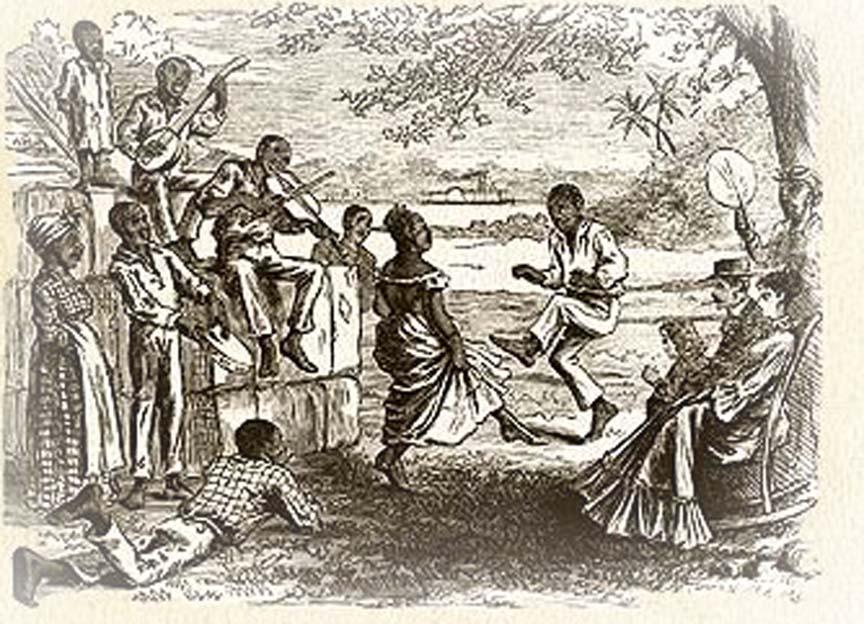

His papa had taught Jonah to play many different instruments, and he passed on this love of music to his son Chunky. And even as an older man, Jonah’s voice was always heard like an angel in church or out singing in the field. “Papa, your grand-pap, played nothing but old hymns, da hymns, papa was regular church man.”

The old man remembered his younger days and said, “When I’s young, I didn’t, just hollered reels, just fiddled and reel, you know, all the time, my singing. Everywhere you hears me you hear me singing a song, a reel. And out in the field that’s what I’d do.

Hollering, singing reels.” One of the youngest listeners spoke very softly, “And what was it you sang about, Jonah, the cotton?” He replied, “About uh, little Joe. Little Joe, my Sam told me to pick a little cotton, the boy says don’t for the seeds all rotten. My Sam told me to pick a little cotton. My boy says don’t, the seeds all rotten. Get out of the way, old Dan Tucker. Come too late to get your supper. That’s all I remembers bout dat one.”

I do remember,” he paused, “Well I’ll tell you, uh, things come to me in spells, you know. I remember things, uh, more when I’m laying down than I do when I’m standing or when I’m walking around. Well, I belonged to, uh, master, when I was a slave. My mama belonged to master, but, uh, we, uh, was all slave children.”

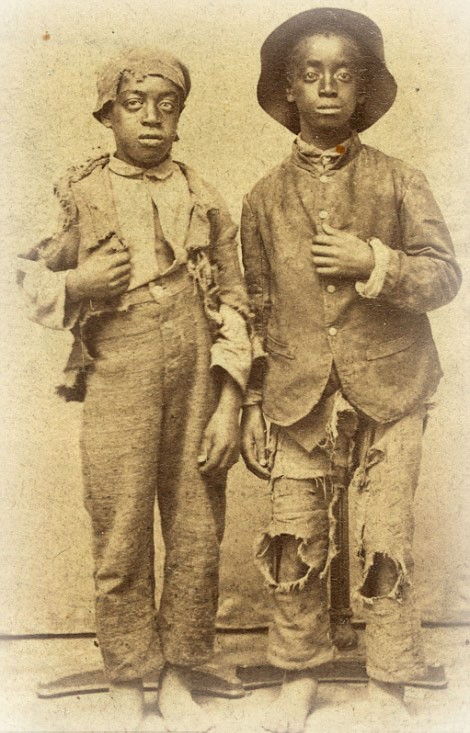

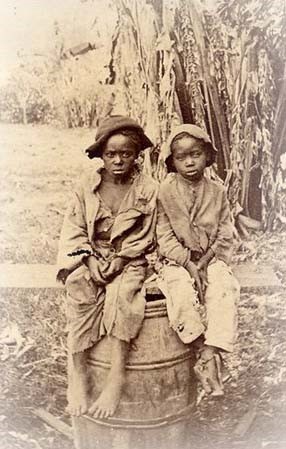

Jonah shared some more memories of his youth with his listeners “Now in my boy days, why, uh, boys lived quite different from the way they live now. But boys wasn’t as mean as they are now either. Boys lived too, they had a good time. The masters da, didn’t treat them bad. And they was always satisfied. They never wore no shoes until they was twelve or thirteen year. And now people put on shoes on babies you know, when they’re two year, when they month old. I be, I don’t know how old they are. Put shoes on babies. Just as soon as you see them out in the street they got shoes on. I told a woman the other day, I said, I never had no shoes till I was thirteen years old.”

She say, “Well, but you bruise your feet all up and stump your toes.”

I say, “Yes, many time I’ve stump my toes, and blood run out them. That didn’t make them buy me no shoes.”

“And back then, I been worn a dress like a woman till I was, I believe ten, twelve, thirteen-year-old,”

A question could be heard coming from under a blanket, from someone with a feminine voice that was thought to be fast asleep, “So you wore a dress, Jonah?”

He answered, “Yes. I didn’t wear no pants, and, of curse didn’t make boys’ pants. Boys wore dresses. Now only womens wearing the dresses, and the boys wearing the pants.”

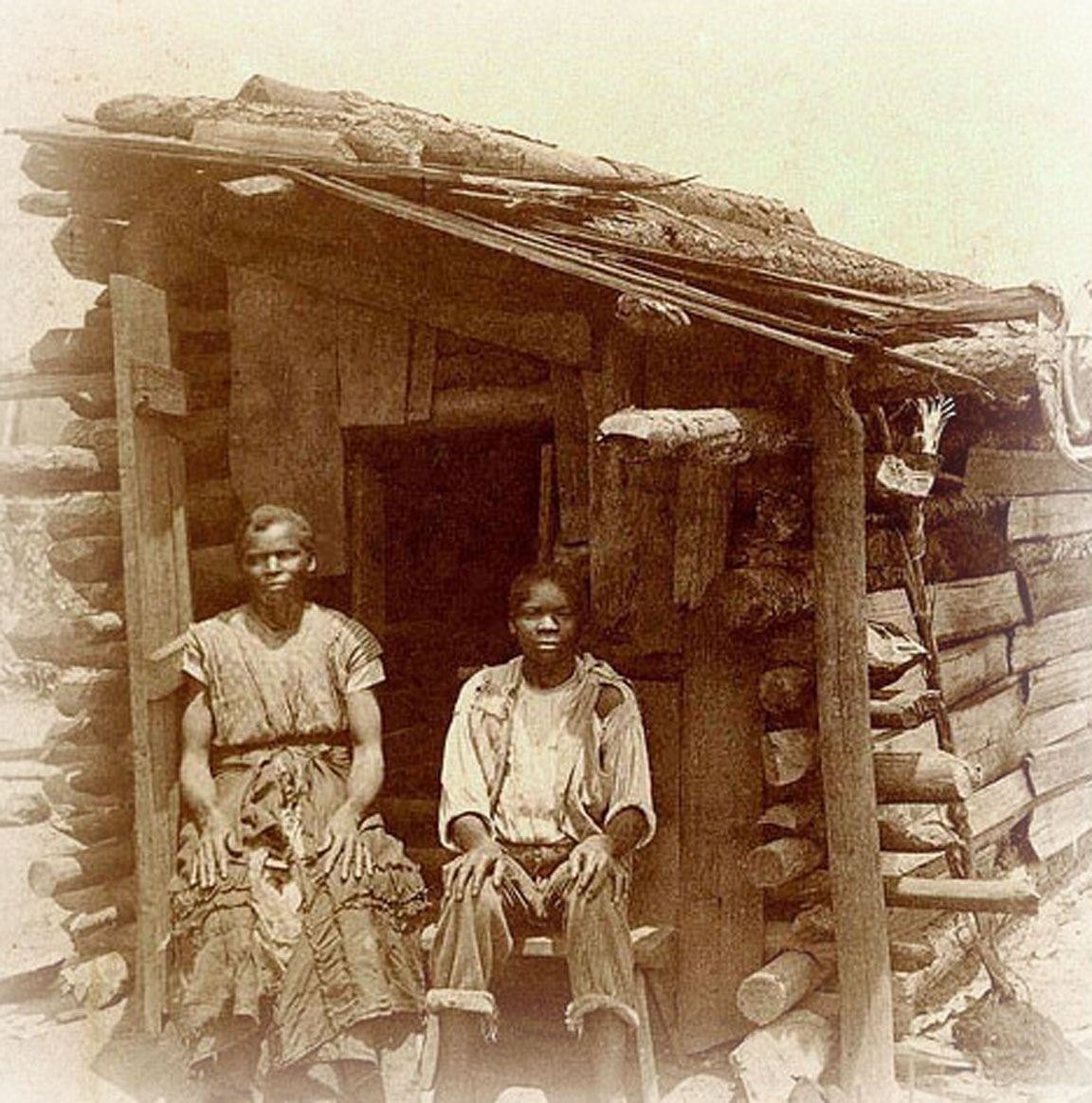

Jonah pointed to the person lying under the blanket and said to her, “Colored people didn’t have no beds when they was slaves. We always slept on the floor, pallet here, and a pallet there. Just like, uh, lot of, uh, wild people, we didn’t, we didn’t know nothing. Didn’t allow you to look at no book. And then there was some free born colored people, why they had a little education, but there was very few of them, where we was.”

The more Jonah spoke to his audience, the more he thought of memories to share with them. “And they all had uh, what you call, I might call it now, uh, jail centers, was just the same as we was in jail. Now I couldn’t go from here across the street, or I couldn’t go through nobody’s house without I have a note, or something from my master. And if I had that pass, that was what we call a pass, if I had that pass, I could go wherever he sent me. And I’d have to be back, you know, when uh. Whoever he sent me to, they, they’d give me another pass and I’d bring that back so as to show how long I’d been gone. We couldn’t go out and stay a hour or two hours, must be something like they send you.”

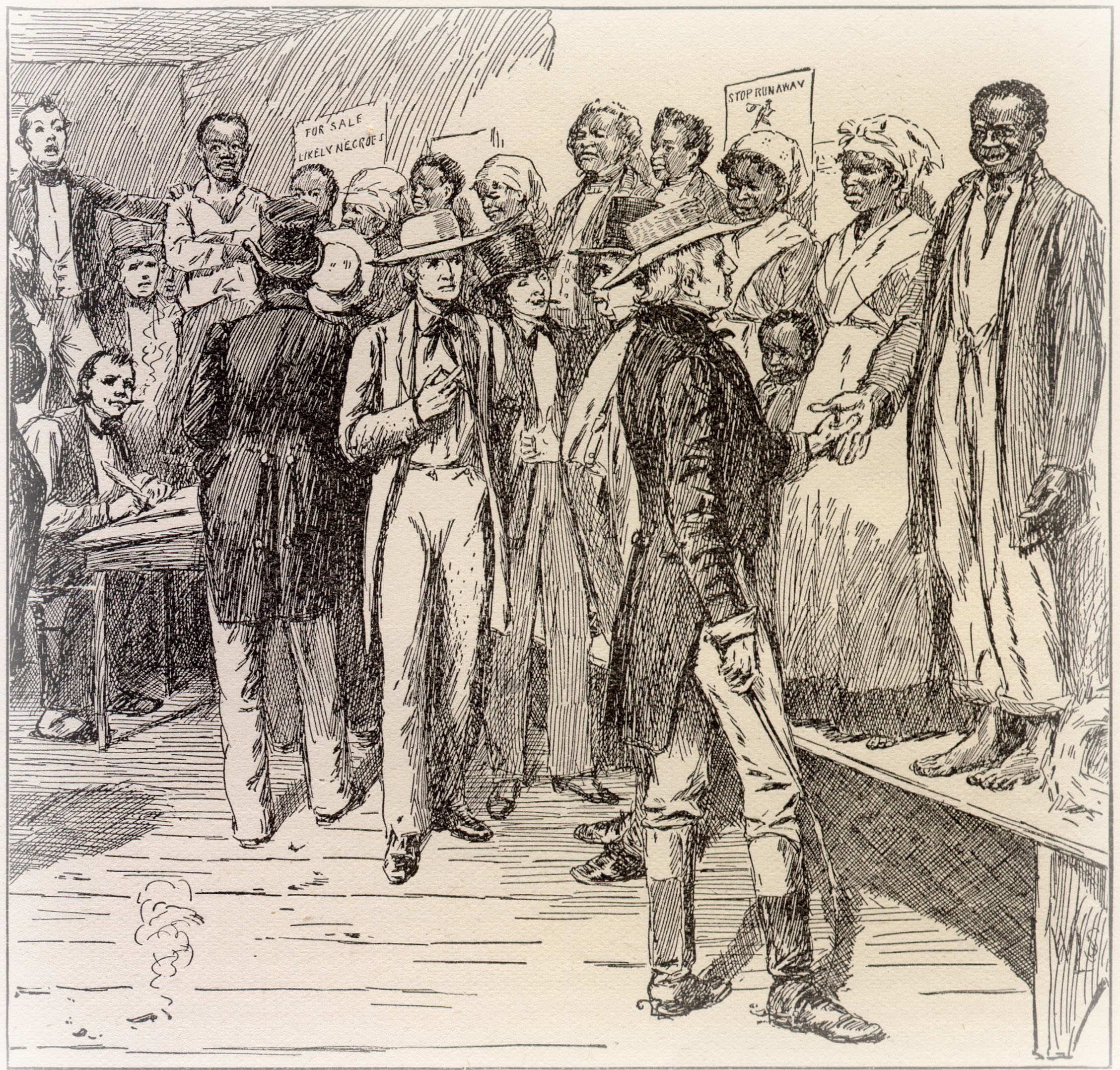

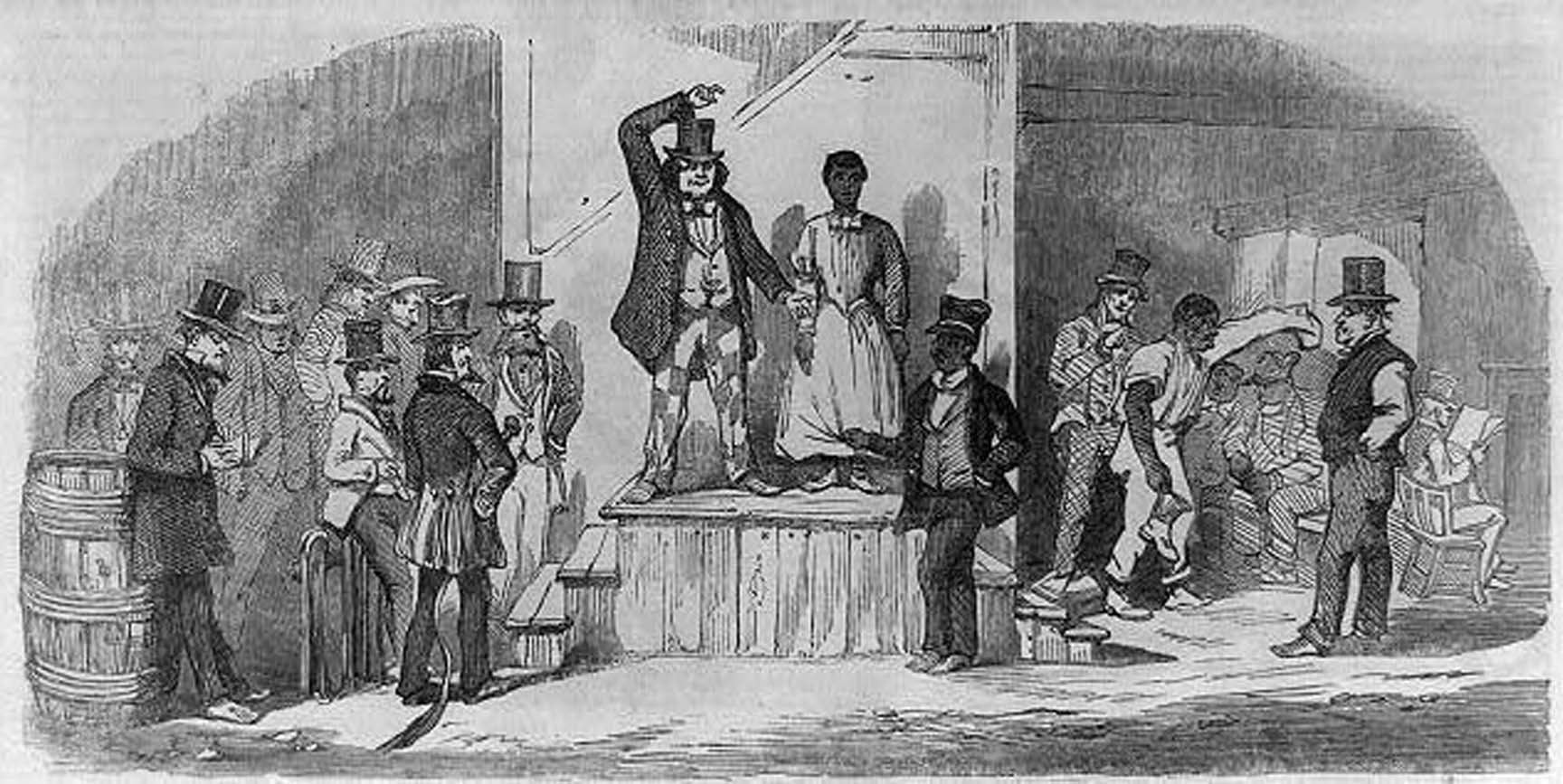

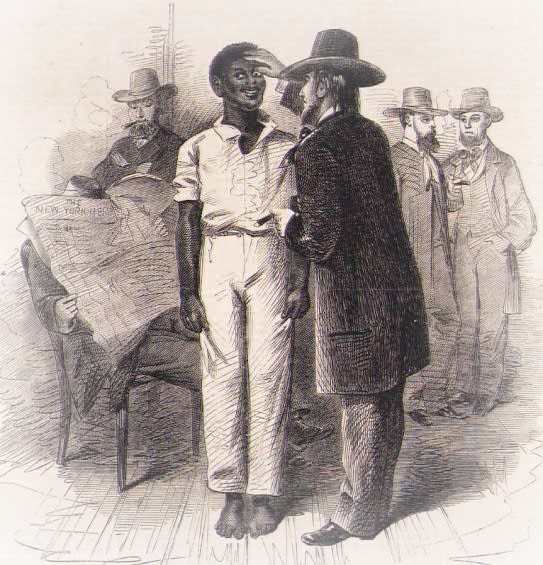

Some of the children were having a hard time believing what they heard. Yet they were eager to hear what Jonah had to say next “But I couldn’t just walk away like the people does now, you know. It was what they call, we were slaves. We belonged to people. They’d sell us like they sell horses and cows and hogs and all like that. Have a auction bench, and they’d put you on, up on the bench and bid on you just same as you bidding on cattle, you know.”

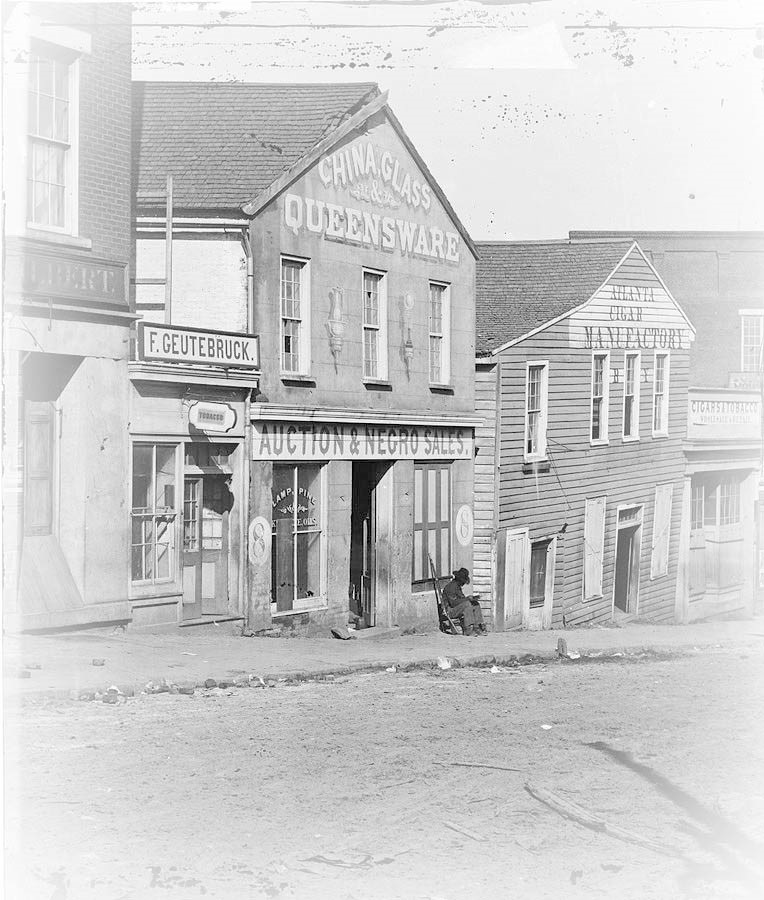

The pain from years ago was very present in his voice when Jonah said, “Selling women, selling men. All that. Then if they had any bad ones, they’d sell them to the Black Traders, what they called, the Black Traders. And they’d ship them down south and sell them down south. But, uh, otherwise if you was a good, good person they wouldn’t sell you. But if you was bad and mean, they want to beat you and knock you around, they’d sell you what to the, what was call the Black Trader. They’d have a regular, have a sale every month, you know, at the courthouse. And then they’d sell you, and get two hundred dollar, hundred dollar, five hundred dollar.”

Jonah stared at the ground, kicked at the dirt under his feet, and said, “Oh, they had a terrible time. Husbands, wives, families, all violently separated, torn apart. Sold to different place, probably never to meet again. Colored people that’s free ought to be awful thankful. When I was in slavery you can’t never do what you want. Now that I’s freed man I can tell me what to do, nobody else. Now in these times you-all here can do what’s ever you want. You can choose which way you go down dat road.” Jonah smiled at them with that toothless grin again.

The children witnessed his big smile melt into a very long sad face. He took a deep breath and began again, “If I thought, had any idea, that I’d ever be a slave again, I’d take a gun and just end it all right away. Because you’re nothing but a dog. You’re not a thing but a dog. Night never comed out, you had nothing to do. Time to cut tabacca, if they want you to cut all night long out in the field, you cut. And if they want you to hang all night long, you hang, hang tabacca. It didn’t matter about your tired, being tired. You’re afraid to say you’re tired. They just say, well work.”

Jonah drifted off into a private memory, and by the dim light of the fading fire, you could see his eyes water.

After a long pause, Jonah took a deep breath and gave out a long sigh. He used his pipe once again as a pointer and motioned up to the heavens. “When papa died, it left us small children just to live on whatever people choose to, uh, give us. I was, I was bound out for a dollar a month. And my mama used to collect the money. Children wasn’t, couldn’t spend money when I come along. In, in, in fact when I come along, young men, young men couldn’t spend no money until they was twenty-one year old. And then you was twenty-one, why then you could spend your money. But if you wasn’t twenty-one, you couldn’t spend no money.”

Jonah kept on speaking but got a little quiet when he said, “And my mama, she bound us out for a dollar a month, and we stay there maybe a couple of year. And, she’d come over and collect the money every month. And a dollar was worth more then, than ten dollars is now. And I, and the men used to work for one dollar a month, twelve dollars a year. Used to hire that a way. And, uh, now you can’t get a man for, five dollars a month. You paying a man now five dollars a month, he don’t want to work for it.”

There was a long pause. Finally, someone broke the silence, “You’re not getting tired, are you Jonah?” When he did not answer right away, all who were still awake assumed the answer was yes.

But after taking a long breath and looking around at who was still up, Jonah began again. “I was thinking about oh, now you know how we served the Lord when I come along, a boy? We would go to somebody’s house. And uh, well we didn’t have no houses likes they got now, you know. We had these what they call log cabin. And they have one, old colored man maybe one would be there, maybe he’d be as old as I am. And he’d be the preacher. Not as old as I am now, but, he’d be the preacher, and then we all sit down and listen at him talk about the Lord. Well, he’d say, well I wonder, uh, sometimes you say I wonder if we’ll ever be free. Well, some of them would say, well, we going to go ask the Lord to free us.”

Jonah folded his hands together, closed his eyes, and began to pray, “Our father who art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done. Give us this day our daily bread. Just like in that day. Deliver us not only from temptation but deliver us from sinning or and forever dying. Oh, calling on our God this night.” Jonah opened his eyes and raised his hands to the sky, “Whereas old time days. Calling down on all of you this night. Calling on you holy, holy days. Oh a, Lord have mercy. Your mercy keeps us going. Sometime up. Sometime we are down Lord. Oh, Lord. Prophet give me. We are poor, tore down. Oh Lord King, help us round and round about way this evening for Jesus. Oh, Lord, have mercy. Your mercy give us strength. Oh, calling on our Lord God this night. Oh, Lord up there in heaven. Oh, Lord. Take us there oh Lord. We don’t want to wear these chains. Oh, what you need, put it in the trust of the same God of Israel.”

Jonah braced himself with his hands on his knees and stood up slowly. He looked around for some more wood to put on the fire. Large sparks hurled themselves skyward when he tossed on more fuel and brought the fire back to life. The light from the flames lit up the faces of the listeners, and to his surprise, all eyes were open.

Almost at once, two children asked the same curious question. “Just how old are you, Jonah?”

He had a great big toothless smile when he answered them, “I really don’t know. I born in slavery. Now I can’t tell you my own age. Hmm? You know why I say, I don’t really like to talk about it. I don’t know my own age, but I was born in slavery. I didn’t born free. I born in the old slavery. That’s the time I come up.”

”

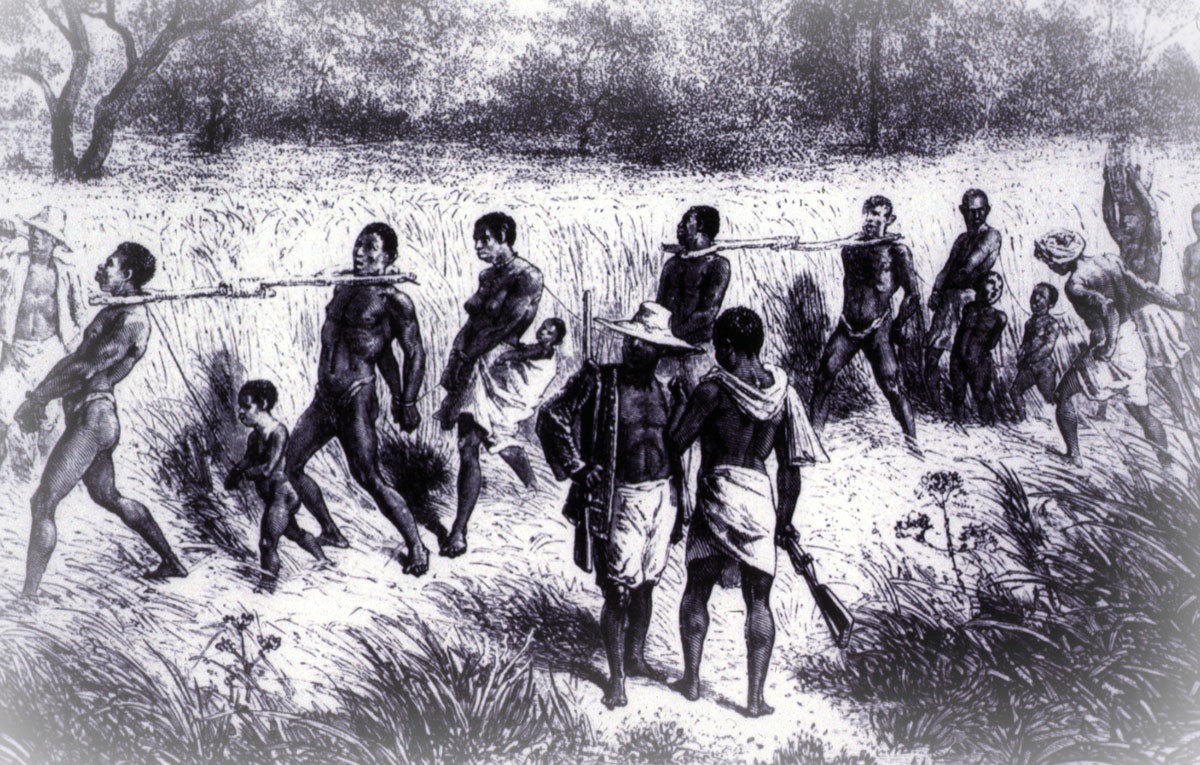

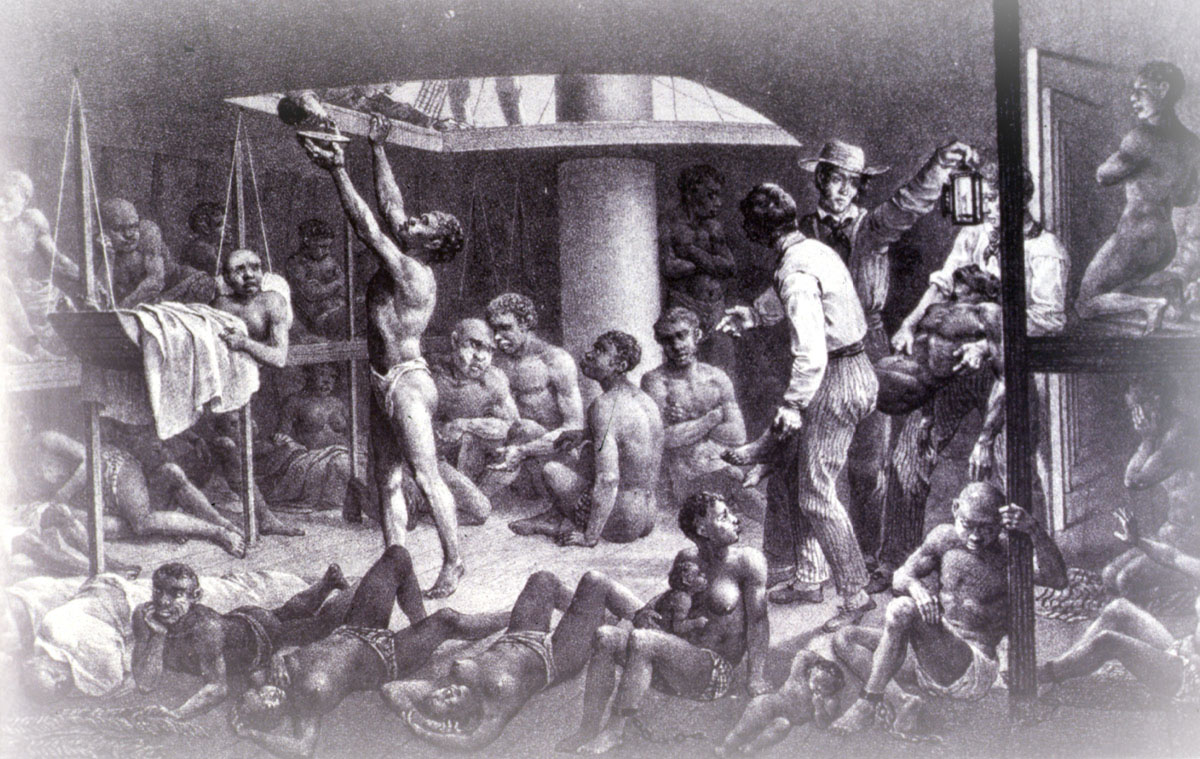

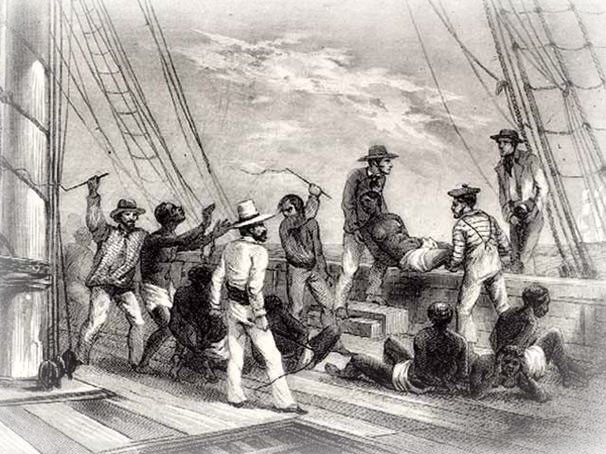

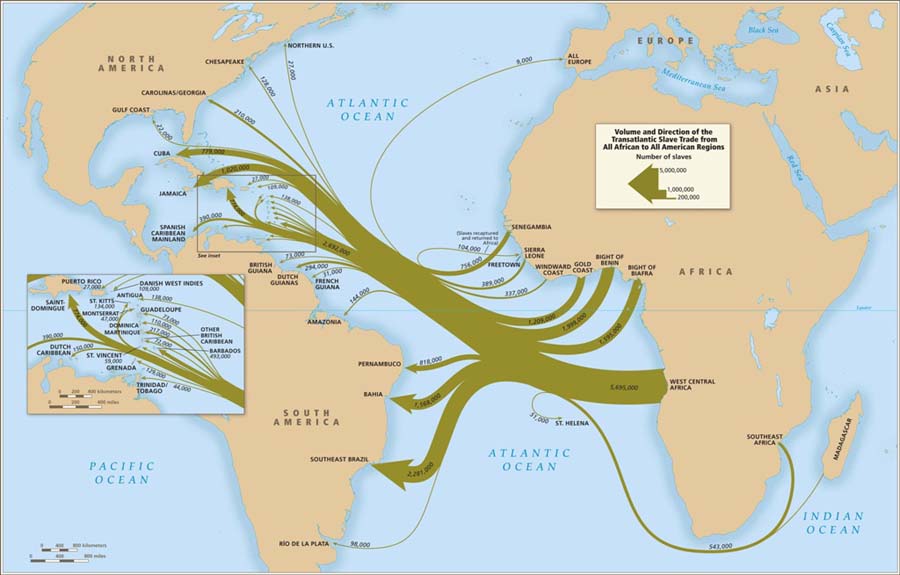

Jonah relit his pipe. He took a big puff and blew out a perfect white smoke ring. Then poked his finger right through the center of it as he began to finish his storytelling. “I was born in that, uh, born in Africa. And come to the United States. You see that was in slavery time. They sold the colored people. They sold the colored people. And they bringing them from the Africa. And they brought me from Africa. I was a boy child.”

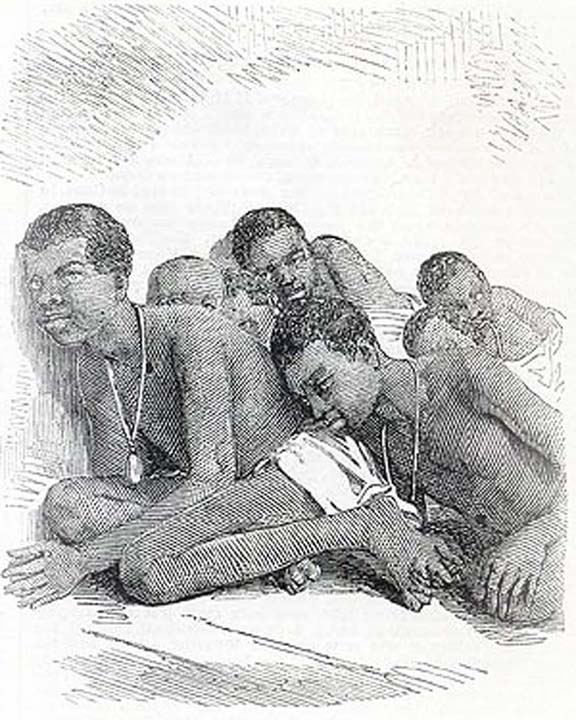

All the captive colored people on a slave ship had a horrible time. Jonah experienced this, not only as a slave but also as a small motherless child chained to adults that were fighting for food and water. They kept the men and women separated on the slave ship. Jonah had to fight for survival as a small child chained to men that wanted to kill him for his rations.

He spoke with a real fear in his voice, “The colored folks want to throw me off the boat coming from Africa. Them other coloreds say,”

“Throw him overboard!”

I was in cuffs. Just a sprout boy child chained in cuffs.

They all shout, that the Black traders, “Throw him overboard, let the damn whale swallow him like he done Jonah.”

“Hadn’t have been, the colored one want to throw me off, hadn’t have been for the Captain of the boat. Captain of the boat was a white man, but the colored is the one wants to throw me off the boat. The colored, the colored people always did hate me from a child. Bringing me from Africa, the colored want to throw me off the boat. They say,”

“Throw him overboard, cuss. Throw him overboard. Let the, cuss, let the cuss just go feed the whale.”

Another puff, another smoke ring, and he continued, “They bring us from Africa, Liberia Africa, where I was brought from. And put in the United States. Me know, the southern people bought colored folks, put you up on a block and sell you, bid you off. The highest bidder gets you. Highest bidder gets you. And they got to mistreating them so.”

Jonah told how he came to America “Oh. I was in, in uh, when they went to New Orleans, that’s where they sold the people. The man that raised me, he buy me. The man raised me buy me. They would try to put you up on the block to sell you. He was master Jake. The man was master Jake.

He name me Jonah that’s the name I go in now. Jonah. He name me. Jonah cuse them coloreds want to toss me to that whale. I got my last name some time ago, later.”

Africa and Transatlantic Slave Trade to North America

>>>Click here <<<

Next: The Chunky story – part 2 – picture book – 1