New York Herald

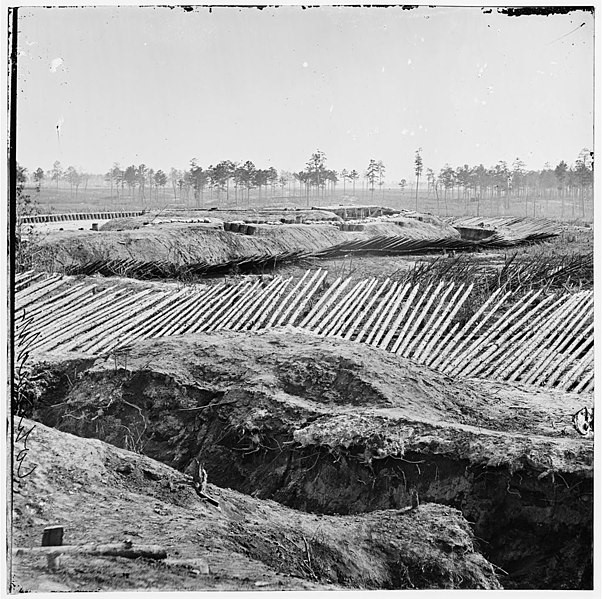

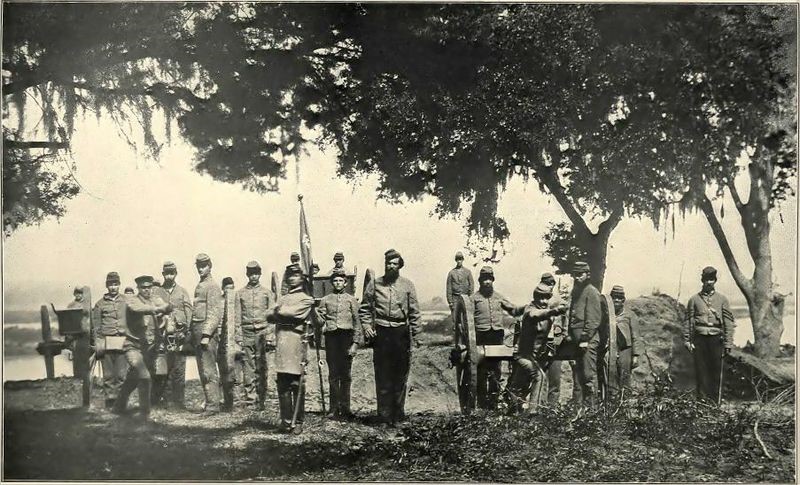

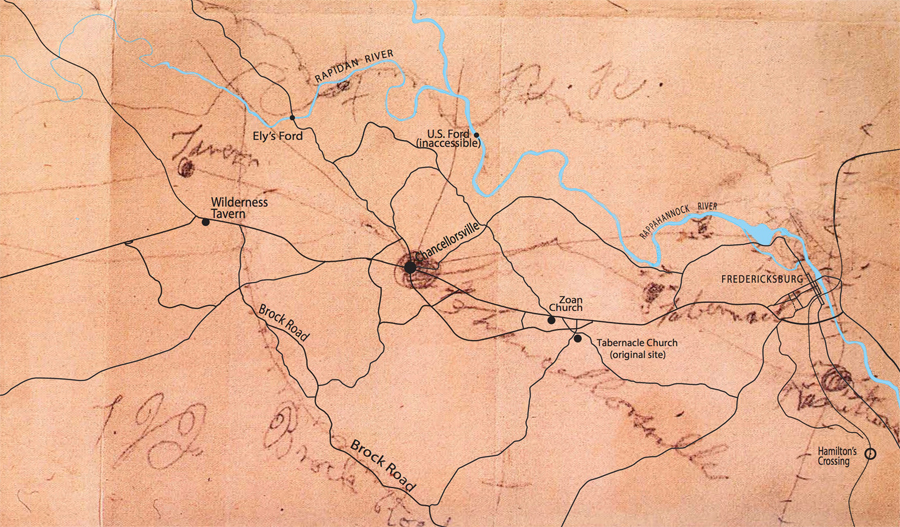

In the battle’s opening in the Chancellorsville campaign, David had been detailed to a detachment of men on skirmish duty. He was among the first to discover the approach of the Jackson skirmishers. The slashings of the trees had been done under the direction of the General in person. They were of the nature of abatis (field fortification).

No date:

One of the men I recall who was detailed with me to assist in the cutting of the trees in front of the line was Andrew Seigler. He rode a sorrel mare. He was one of the first men killed from the regiment. I still have a letter we started to write together to his wife in my haversack. I will try to send it to her on the next mail call.

Now David was spending more time with officers, doing things he could not talk to the other men about. He felt like “the chief, cook, and bottle washer” because he had so many jobs from one end of the shovel to the other end of the spyglass.

Abatis is a field fortification

About this time, Sergeant Kiefer reported the woods in front of the troops were being amassed with men behind the thickets for a charge. David found out that by crouching down, he could see their legs up to their knees and saw that the force was a large one. The Sergeant was captured later near the Almshouse and was a prisoner for several weeks, but he was paroled. The Union Army was driven back by the Rebels at Chancellorsville on the afternoon of May 2. Captain Oerter of Company C was doing his best to rally the retreating soldiers. David, along with some other brave men, remained with him as long as they could. But when it got too warm, he found it would be madness to continue there any longer. When David followed the men to the rear and entered the woods, he discovered a mistake. They found themselves in the rear of the enemy who had advanced its lines in pursuing their forces.

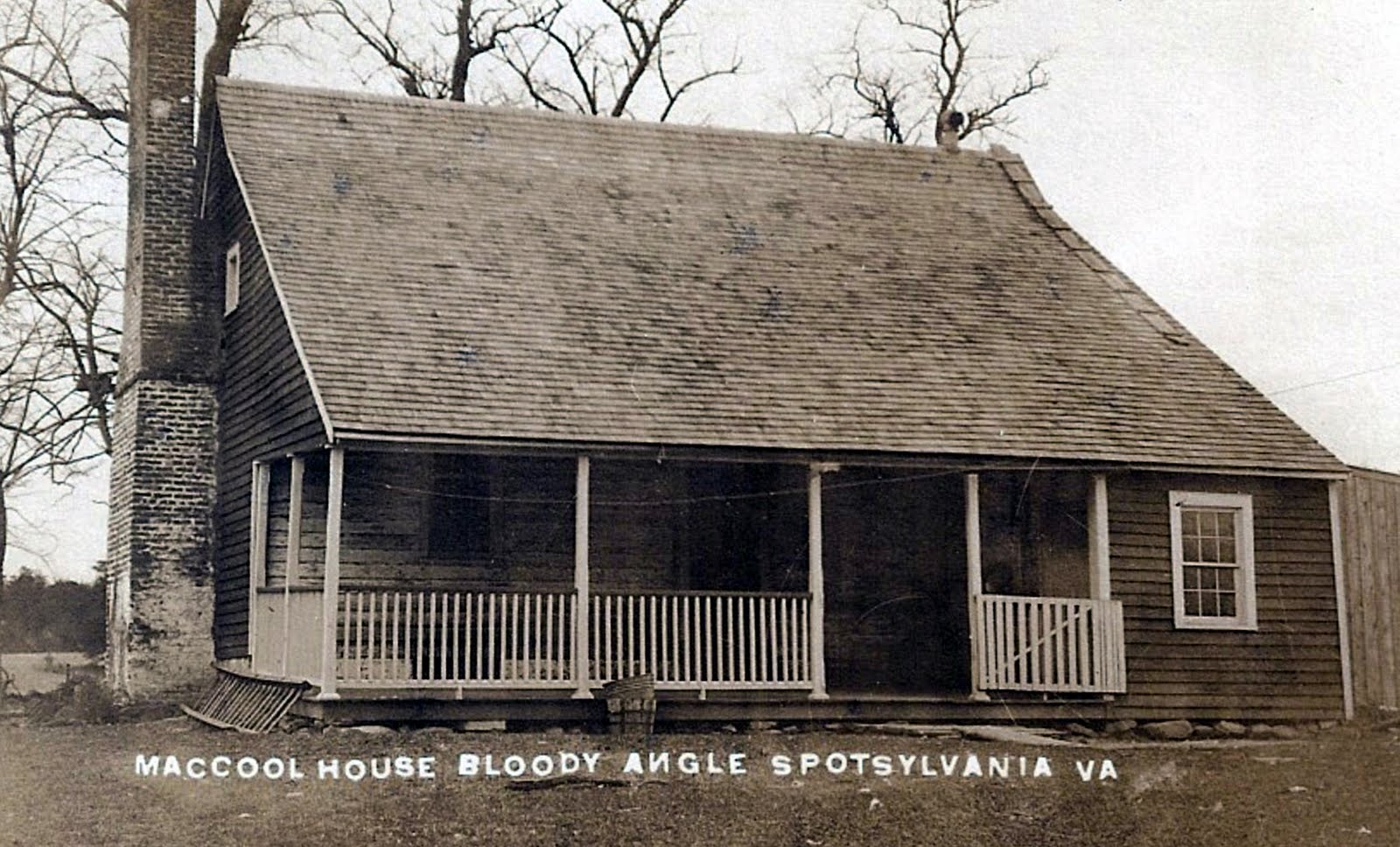

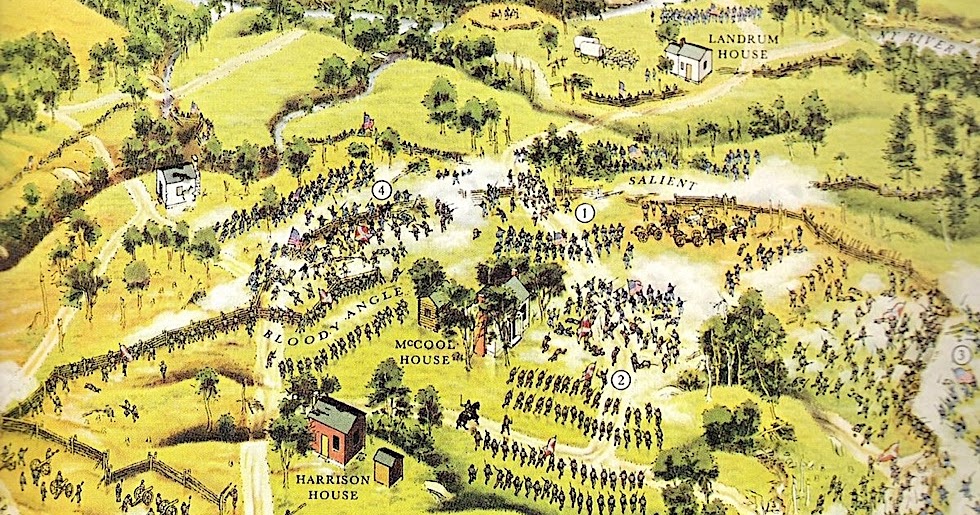

The McCool House

No date:

I spent the entire night trying to get out of the woods and eluding some of the enemy’s scouts. I drank water from the spring, near the McCool house, which slaked the thirst of many of the wounded and dying of both armies during the memorable siege.

In the battle of Chancellorsville, David’s regiment occupied a unique position at the extreme right of the Army of the Potomac. It was the first to receive the attack of Stonewall Jackson’s Corps of Lee’s Confederate Army. During the attack, a rebel bullet grazed one of his fingers, merely breaking the skin. As he lay on the field, David was in danger of being shot again by his comrades. That this did not occur was entirely owing to the kind services of a Confederate soldier.

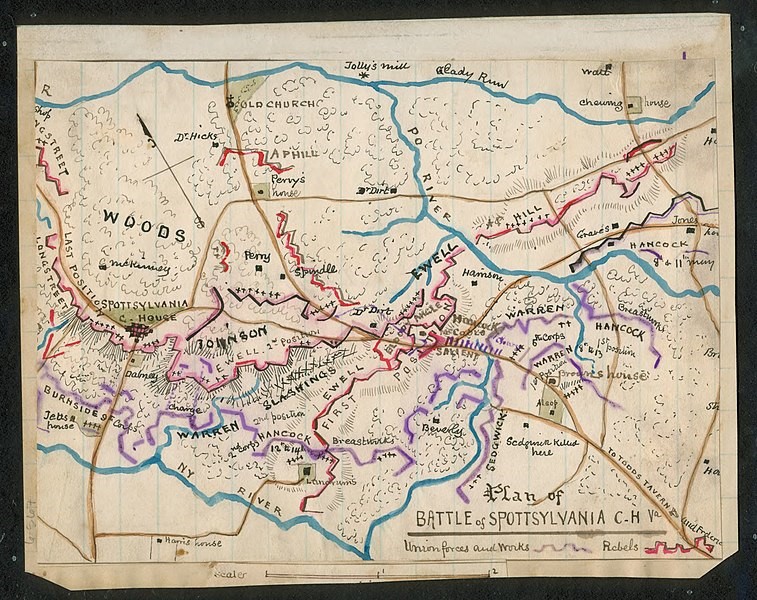

Spotsylvania Campaign

Nearby there was a clump of large trees that David and his men helped cut down. Now in the enemy’s line formed in the rear was one particular Rebel who took advantage of the protection afforded by these fallen trees.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse

As the balls from his own Union forces were flying fast all around him, David asked the Rebel to place a large, loose tree stump that lay a short distance away in front of him. “I don’t like the idea of being hit by my own regiment,” David said.

The Reb kicked the stump toward him, almost hitting him in the face. Hardly had the Rebel gotten back behind his tree when three minie balls struck the stump in front of David. “Young man, I saved your life,” called the Rebel. David was not scant in his thanks, as may well be imagined.

Confederate artillery

The Rebel was more talkative than David was, and he listened to him chatter until it got dark. Then the Confederate soldier just stood up and walked right over to David and sat down with him behind the stump fortress. “I got some tobacco and some good corn squeezin’s, and I be will’in to trade for some real coffee,” the Rebel boasted as he showed off his jug.

It was very obvious to David that the man from Dixie had already been squeezin’ the corn because he sat down hard enough on his fanny to lose his breath for a second. He did not give David any chance to answer before he started talking again. “Don’t worry, none, no one is watching us here, they all watching the fireworks from that-thar artillery,” the Rebel pointed to the shells overhead.

David had some hardtack with him, and he gave it to the Rebel along with a good drink from his canteen. Then the Rebel left him in the dark, but not before giving David some good southern tobacco and a pull on his jug of whiskey.

The Rebel shells exploded over the men all night in mass quantities. David was lying on his back, supported on his elbows, watching the shells explode overhead. He was speculating as to how long he could hold up his finger before it would be shot off. The very air seemed full of bullets. When the order to “get up” was given, David turned over quickly to look at Col. Kimball, who had given the order, thinking he had suddenly become insane. It was as if the order was never given, for Col. Kimball did not repeat it, and the men did not obey it.

While lying on the field, out of nowhere came a boy by the name of Aaron Meyers of Co. D. He had a flesh wound in his leg, yet he still carried water to David as he took cover. David cautioned the younger soldier to be careful, but he saw his body a short while later on the field. His canteen lay beside him with more than one bullet hole in it. Someone had played sharpshooter on the canteen that brought David water before shooting the young soldier dead.

Water from an angel

In the morning of Sunday, May 3, David got up and started for the regiment but didn’t get very far before he found himself in the line of the Rebs. They had set out pickets during the night, so he had no way but to be captured. He was marched about 2 miles to a field and joined there by a squad of about 150. They waited for about an hour, then another squad of about 1000 came up. Finally, they were marched off, arriving at Spotsylvania Court House, where they slept in the jail yard until morning. David awoke to relieve himself, and, under the bright light of a full moon, he jotted down some notes.

Spotsylvania court house

May 3, 1863:

I was captured in the battle of Chancellorsville, at about 8 o’clock in the morning, and about one mile from our Saturday’s line of battle. In company with 4000 prisoners. I marched to Spotsylvania court house, where we were kept overnight in the jail yard. Having two gum blankets, I shared with Colonel Glanz, he and I sleeping together. On the next morning, we left for guinea station. While resting on the way, the colonel gave me money requesting me to buy him a pair of shoes., as he found it very hard marching in his high-topped boots. After a long search, I found a pair, but which proved to be too small for him. I then started out and exchanged them for a larger pair, which were all right. I also carried his overcoat for him on the march. We remained at guinea station three and a half days, during which time Stonewall Jackson was brought here wounded. He died before we left, only a short distance from our camp.

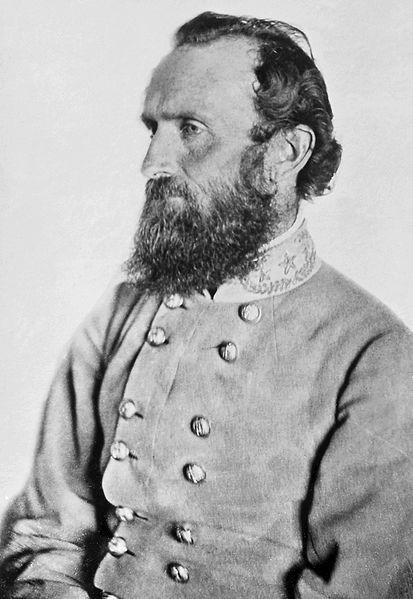

General Jackson’s “Chancellorsville” portrait, taken at a Spotsylvania County farm on

April 26, 1863, seven days before he was wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville

Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson rose to prominence. He earned his most famous nickname at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas, as Confederates called it) on July 21, 1861. As the Confederate lines began to crumble under the massive Union assault, Jackson’s brigade provided crucial reinforcements on Henry House Hill, demonstrating the discipline he instilled in his men.

Stonewall Jackson’s last map

Brig. Gen. Barnard Elliott Bee, Jr. exhorted his own troops to re-form by shouting, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!” He was killed almost immediately after speaking.

Jackson has since then been generally known as Stonewall Jackson. During the battle, Jackson displayed a gesture familiar to him. He held his left arm skyward with the palm facing forward; this was interpreted by his soldiers as a prayer to God for success in combat. His hand was struck by a bullet or a piece of shrapnel and suffered a slight loss of bone in his middle finger. He refused medical advice to have the finger amputated.

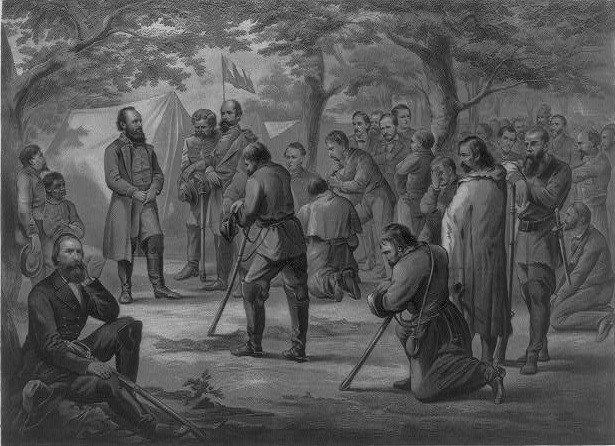

Prayer in Stonewall Jackson’s camp

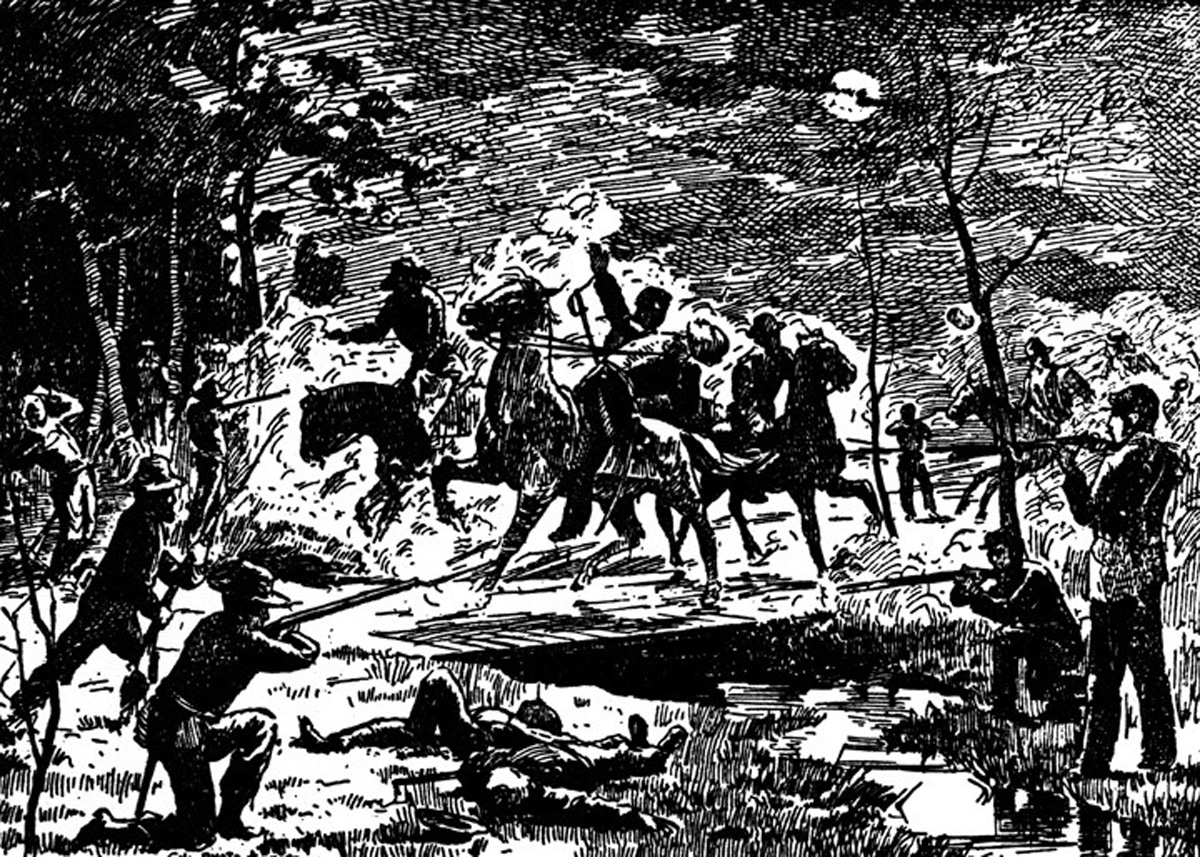

Darkness ended the assault. As Jackson and his staff were returning to camp on May 2, they were mistaken for a Union cavalry force by the 18th North Carolina Infantry Regiment. His own soldiers shouted, “Halt, who goes there?” but they fired before evaluating the reply. Frantic shouts by Jackson’s staff identifying the party were replied to with the retort, “It’s a damned Yankee trick! Fire!” A second volley was fired in response, and in all, Jackson was hit by three bullets, two in the left arm and one in the right hand. Several other men in his staff were killed, in addition to many horses.

Stonewall Jackson is shot by his own men

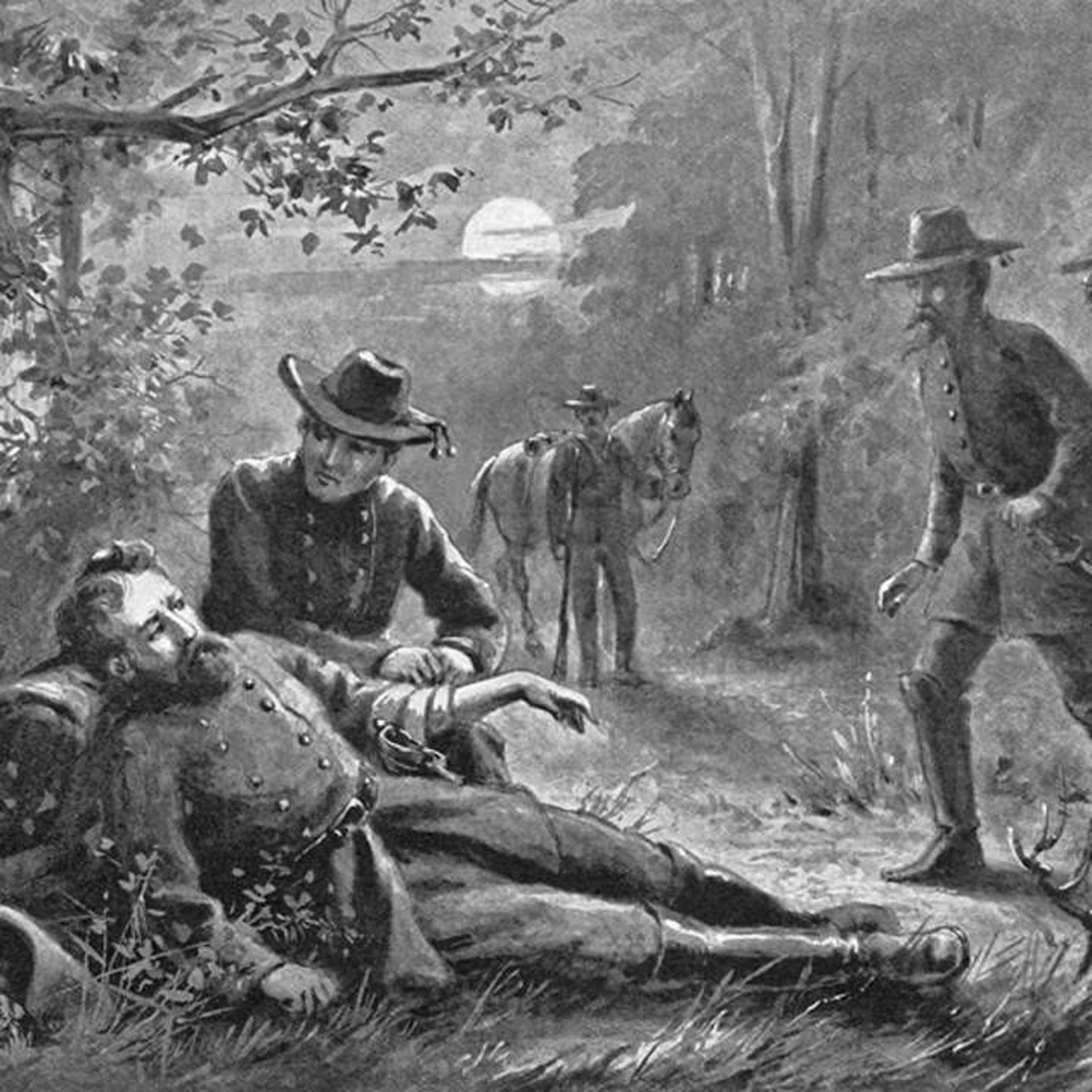

Darkness and confusion prevented Jackson from getting immediate care. He was dropped from his stretcher while being evacuated because of incoming artillery rounds.

Jackson is dropped being carried from the field

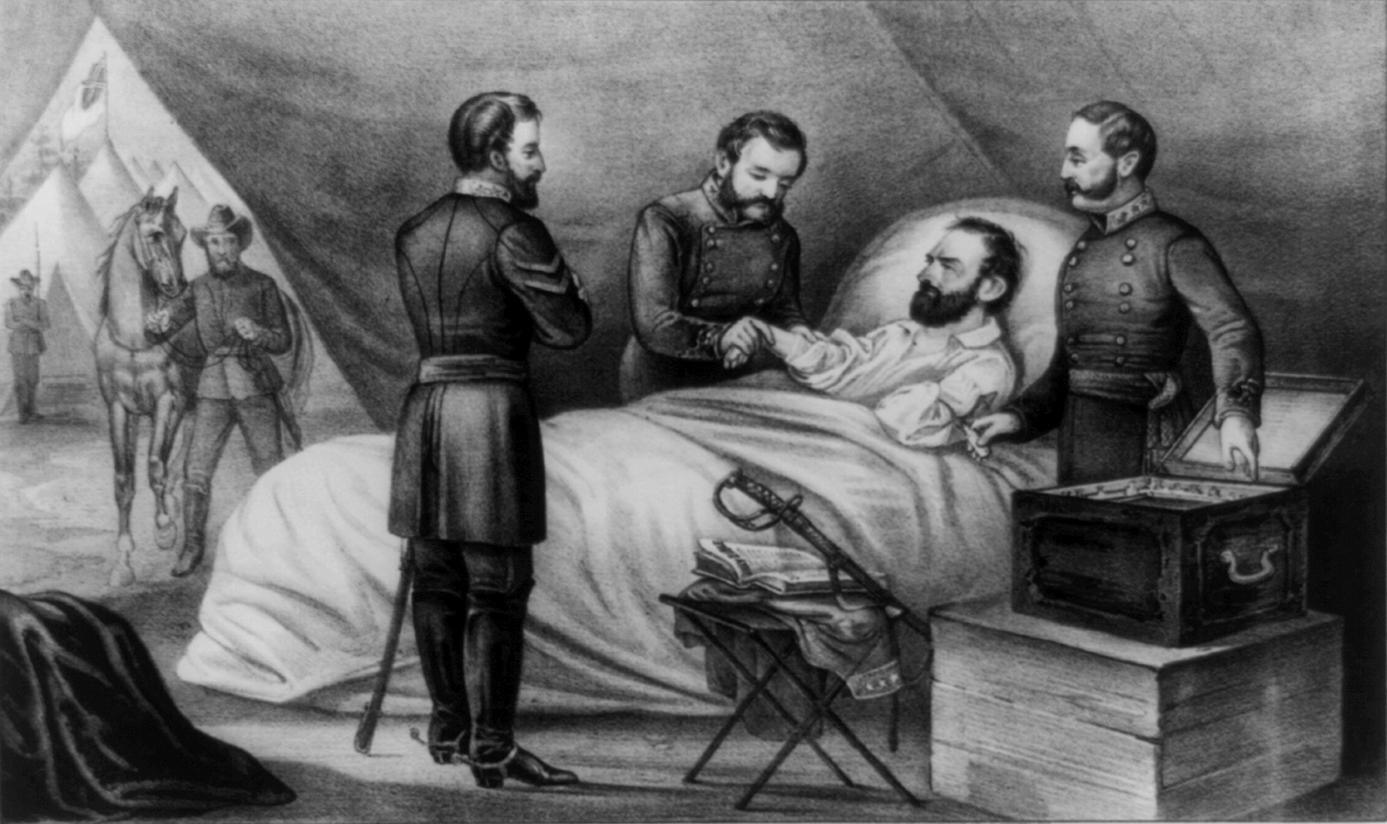

Because of his injuries, Jackson’s left arm had to be amputated by Dr. McGuire. Jackson was moved to Chandler’s plantation named Fairfield. He was offered Chandler’s home for recovery, but Jackson refused and suggested using Chandler’s plantation office building instead. He was thought to be out of harm’s way, but unknown to the doctors, he already had classic symptoms of pneumonia, complaining of a sore chest. This soreness was mistakenly thought to be the result of his rough handling in the battlefield evacuation.

The plantation office building where Stonewall Jackson died in Guinea Station, Virginia

Dr. McGuire wrote an account of Jackson’s final hours and his last words:

A few moments before he died, he cried out in his delirium, “Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks”—then stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently a smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face. Then he said quietly, and with an expression, as if of relief, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

“Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees”

His death was a severe setback for the Confederacy, affecting its military prospects and the morale of its army and of the general public. Jackson, in death, became an icon of Southern heroism and commitment. He became a mainstay in the pantheon of the “Lost Cause.” Military historians will consider Jackson to be one of the most gifted tactical commanders in U.S. History. Jackson’s tactics will be studied worldwide as examples of innovative and bold leadership.

David and the other captured Union Soldiers spent all day marching until about 6 in the evening. They were allowed to rest for about 15 minutes then forced to start again. The men marched about 1 mile and forded a creek about ½ mile wide and thigh deep. The Rebel guards marched them into the woods and made camp. It rained all night, and the men did not get much sleep all wet. The following day the Rebel guards got them up at 7 am and started the march early for Hanover Station.

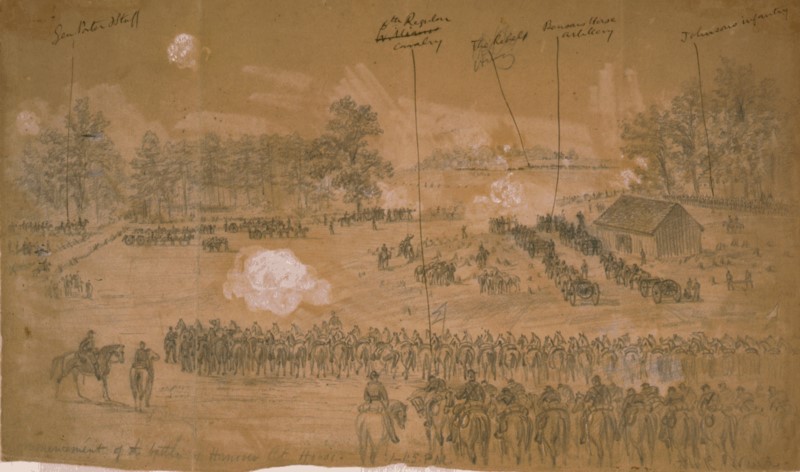

Battle of Hanover Courthouse

Just before they got started, David removed the haversack from his shoulder. He took out the scarf and made his bag into a chair. He sat down to rest, even for a moment, knowing good and well that a hard march was coming. He wrote in his diary.

May 8, 1863:

Raining again this morning. Arrived at Hanover junction at 6 in the evening, still about 30 miles to Richmond. It started on the morning of the 9th. Marched until 9 in the evening, then arrived at the Libby prison; to-day marched through mud and water ankle deep all day, very tired, could hardly stand on one foot anymore, for supper we got nothing.

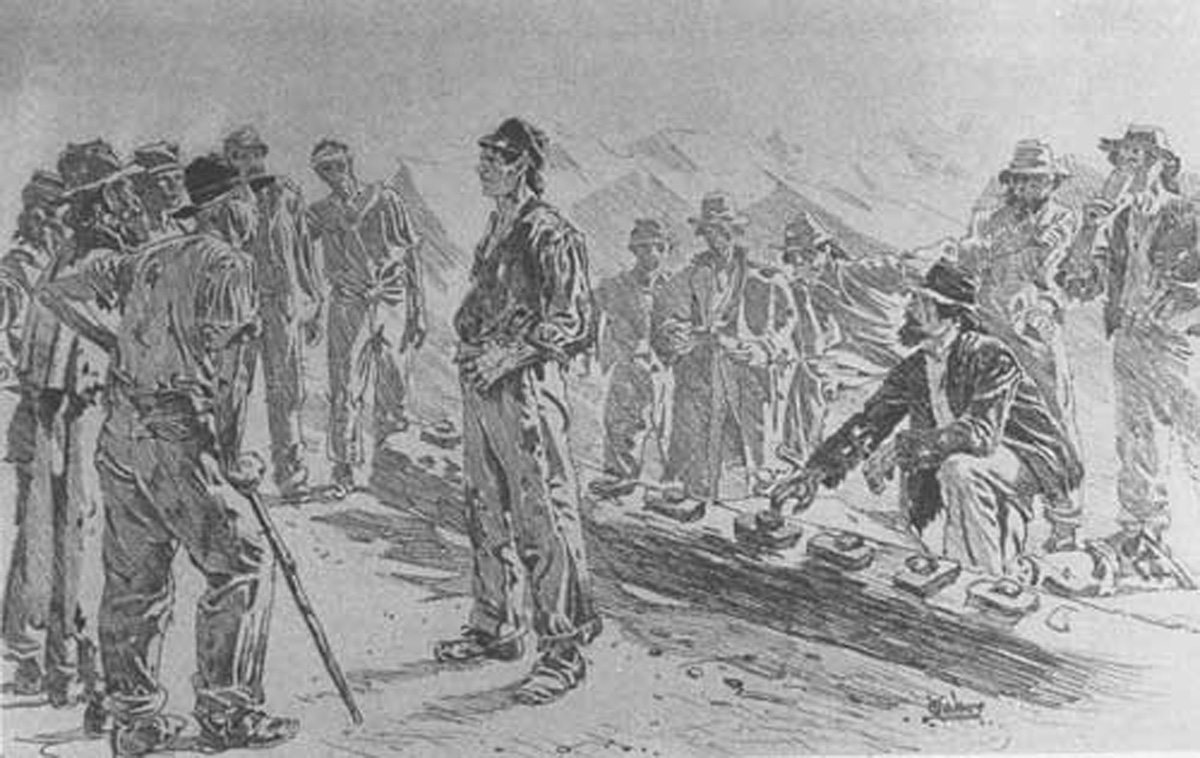

Prisoners being issued rations and trading for something more palatable

May 10, 1863:

Sunday, in the morning at 9, we got about 1 pound of bread and ½ pound pork. In the evening at 9 the same.

May 11, 1863:

Monday, we got nothing till noon, then we got the same in the evening, 1/2 cup bean soup.

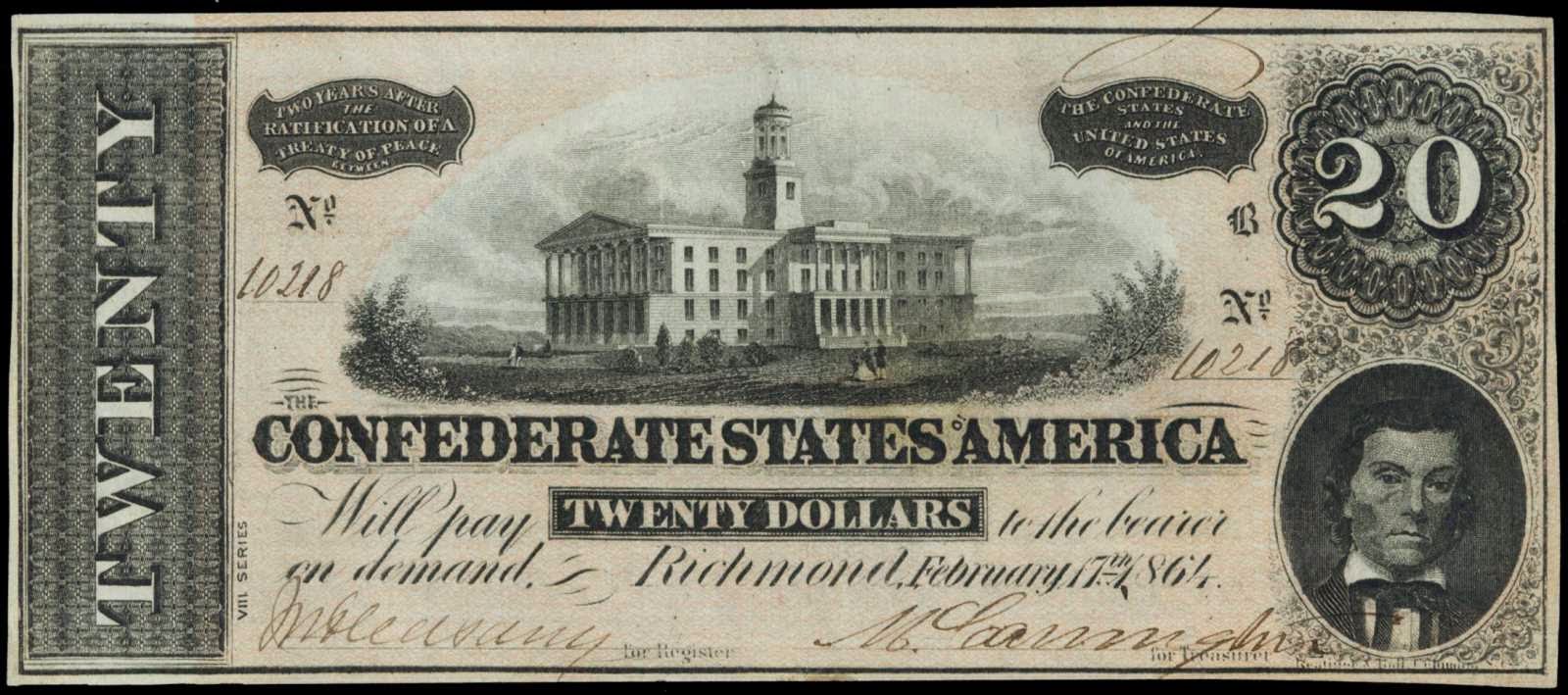

Confederate 20-dollar bill

The Colonel gave David a twenty-dollar Confederate bill requesting him to purchase some cakes from the Rebels for their use. He took a gum blanket in which to carry them. One of the most essential items a soldier carried on campaigns was the water-proof gum blanket. One of these blankets was issued to every soldier in the Union Army to help keep him and his bedroll dry. By the end of the War, all gum blankets were coated with rubber.

David found a Sutler’s tent and laid down the bill for the cakes. A Sutler was a person who followed an army and sold provisions to the soldiers, but he said, “I won’t take that money.”

David asked, “Why not? It is your own money.”

He replied, “Yes, but our money won’t go to England, and yours will.” David returned and reported to the Colonel, who made some remarks that were not very complimentary to the Rebel Sutler.

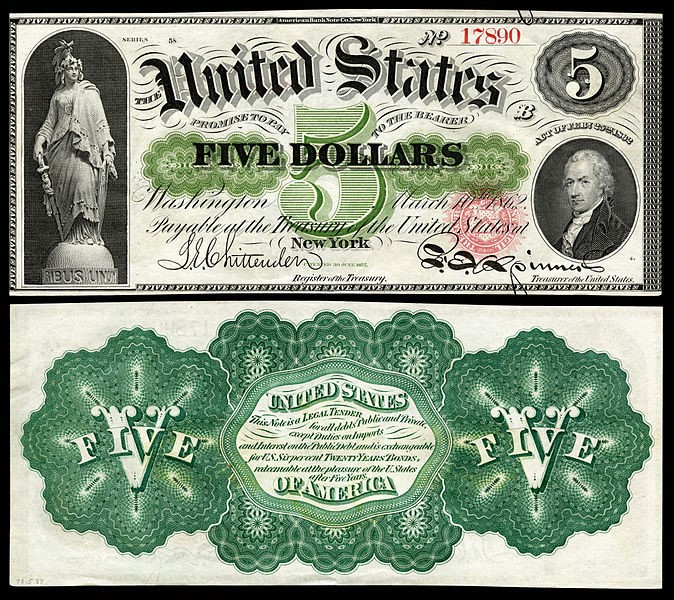

Federal “greenback” 5-dollar bill

On Sunday the 10th, he gave David a five-dollar greenback. For this, they got about three or four pounds of what they called ginger snaps. On returning, he handed them to the Colonel, but he said, “No, pass them among our men.” This was done until there were four of five left; these the Colonel refused, so David ate them.

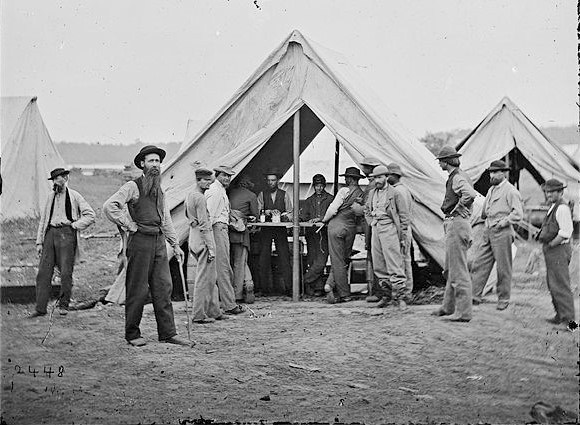

A Sutler tent

A massive thunderstorm arose, and the men were thoroughly drenched. They left the Station on May 8 at about noon and marched to Hanover Junction. Here they remained overnight and had rations dealt out to them, consisting of two crackers and about two ounces of boiled ham to each man.

David asked the Colonel of their guard how far it was to Richmond. He said, “Thirty-two miles boys, and we must march the distance without stopping.” Which they did, excepting short stops for rest. So, off they started with the intention of marching all night. The men were force-marched until about 7 pm. Then the most brutal shower that anyone had ever seen came up, but they wouldn’t let the men stop and made them march on.

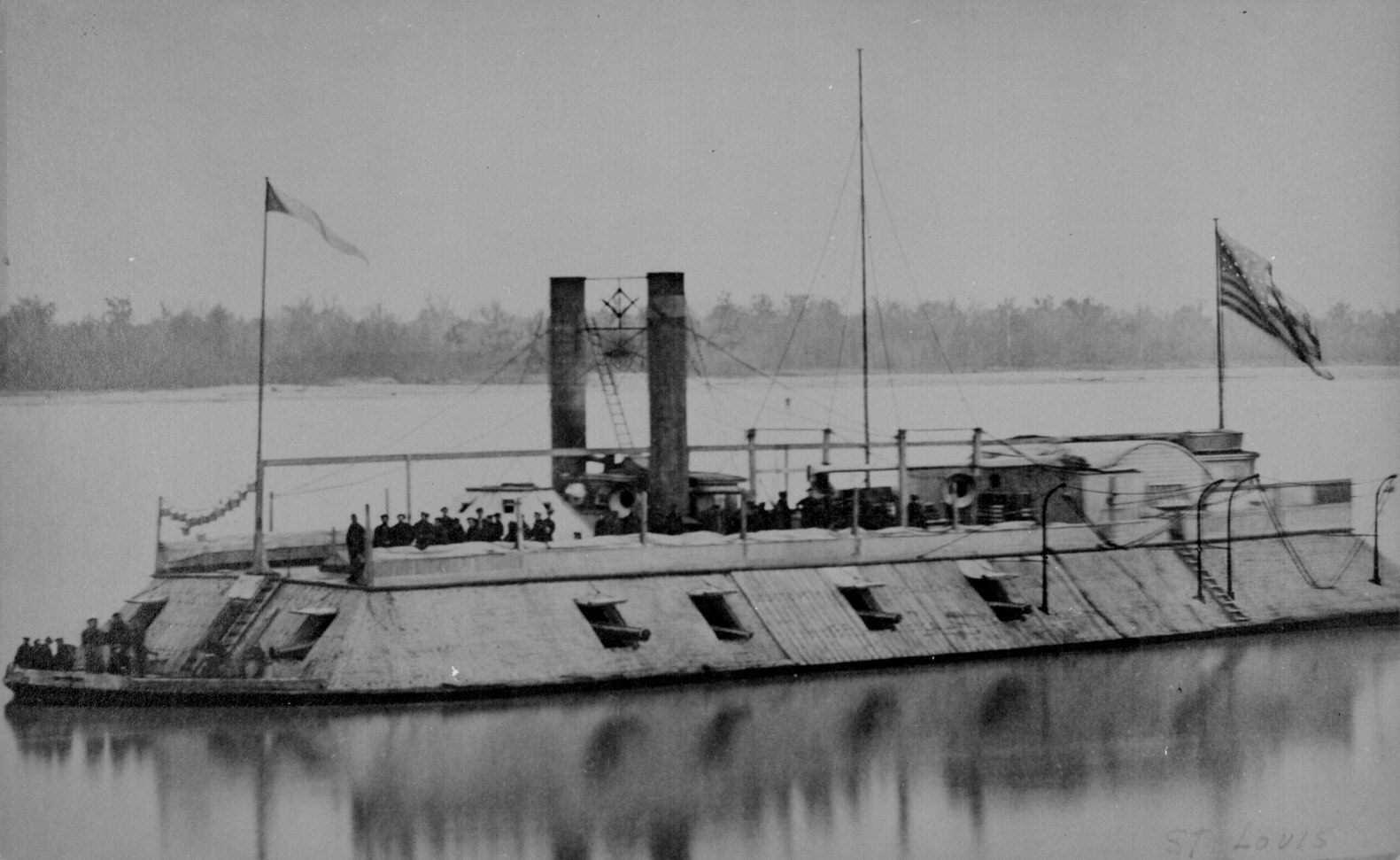

The Rebels kept it until about nine and then let their captives rest for the night. But again, very few got any rest, for it rained. So, the men lay in the wet until the morning of the 14th. David thanked the Lord that he still had his gum blanket. Other men were not so lucky: theirs were lost or stolen. That day they passed thru City Point, a lovely place, but all deserted. It contained some 12 or 15 houses, and all of them were pretty well riddled with shells that McClellan had fired in there from his gunboats.

Union gunboat

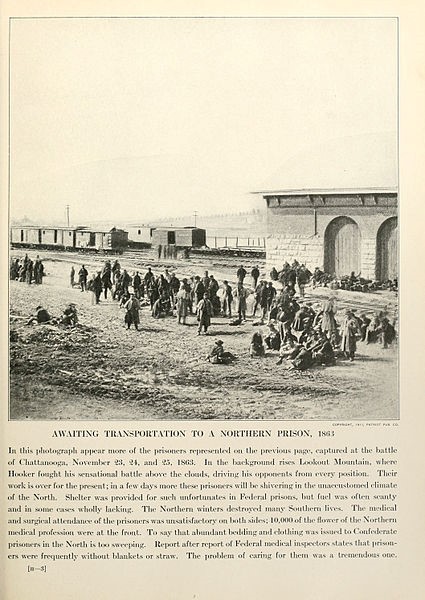

They arrived at Libby Prison at about ten o’clock that evening. About nine o’clock the next morning, they were given a five-cent loaf of bread for eight men. Later in the evening, the men were served with a cup of black bean soup, which was feeble stuff. These rations were a sample of what their daily diet would be during their confinement.

Every day the officer of the floor would come in and say, “Yanks, fall in, in groups of fours.” In this way, they were counted instead of having a roll call.

Libby prison Richmond, Virginia

Union and Confederate forces exchanged prisoners sporadically, often as an act of humanity between opposing commanders. Support for prisoner exchanges grew throughout the initial months of the war, as the North saw increasing numbers of its soldiers captured.

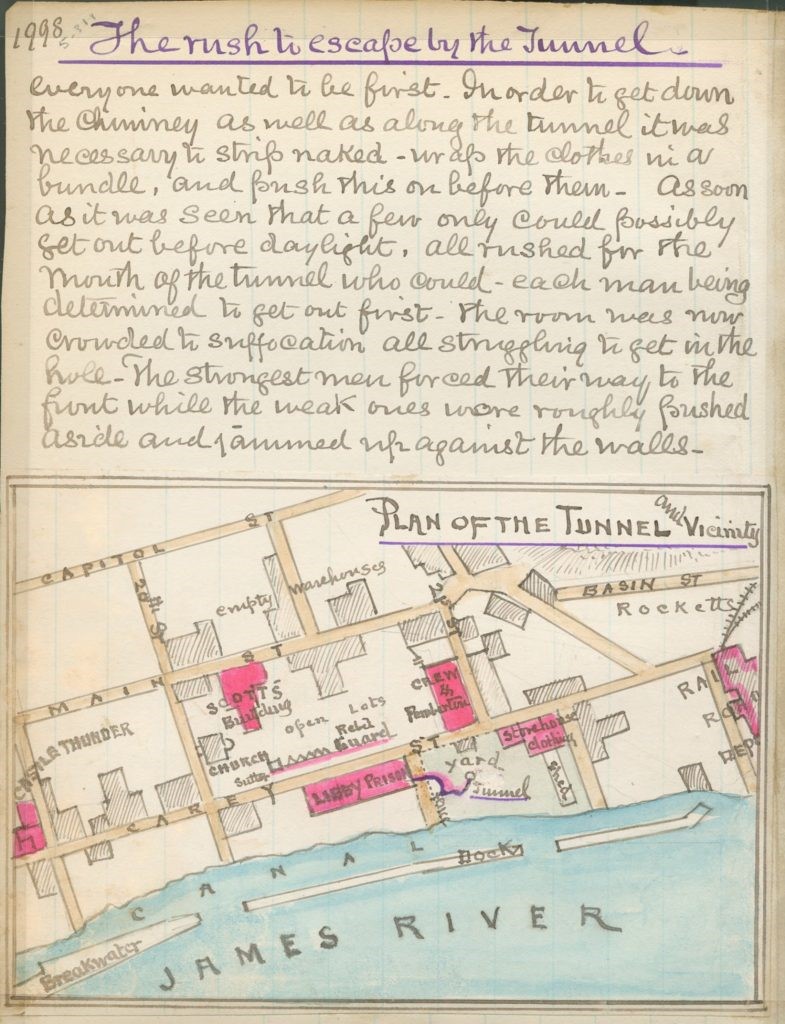

Libby prison escape plan

At the outbreak of the War, the Federal government avoided any action, including prisoner exchanges, that might be viewed as official recognition of the Confederate government in Richmond. Still, public opinion forced a change after the First Battle of Bull Run when the Confederates captured over one thousand Union soldiers.

Being taken to Libby Prison, David thought his time fighting was over. Still, along with several other men, they were only confined for a short period of five days. Then, they were immediately exchanged at City Point and re-joined their regiment. David had experienced some prison time, and now he had to endure the march to Gettysburg. Later he would argue with himself about which one was worse.

No date:

When I came out of prison, confederate women were waiting to supply us with one cent biscuits at twenty-five cents apiece. I paid two dollars for eight biscuits. We marched to Petersburg the first day. We were in the rain all day and all night, but with cover at night. We left the woods about daylight and marched to City Point, a distance of nine miles, and arrived at 2 pm, having marched about 32 miles. We were under escort of cavalry and infantry. The rebels were moving empty cars in the same direction we were going to bring back their prisoners, and they could have taken us on board the cars as well as not.

>>>Click here <<<

Next: The march to Gettysburg – picture book 1